Table of Contents |

As you have learned, the nervous system uses two types of intercellular communication—electrical and chemical signaling—either by the direct action of an electrical potential, or in the latter case, through the action of chemical neurotransmitters such as serotonin or norepinephrine. Neurotransmitters act locally and rapidly. When an electrical signal in the form of an action potential arrives at the synaptic terminal, it diffuses across the synaptic cleft (the gap between a sending neuron and a receiving neuron or muscle cell). Once the neurotransmitters interact (bind) with receptors on the receiving (post-synaptic) cell, the receptor stimulation is transduced into a response such as continued electrical signaling or modification of cellular response. The target cell responds within milliseconds of receiving the chemical “message”; this response then ceases very quickly once the neural signaling ends. In this way, neural communication enables body functions that involve quick, brief actions, such as movement, sensation, and cognition.

In contrast, the endocrine system uses just one method of communication: chemical signaling. These signals are sent by the endocrine organs, which secrete chemicals—the hormones—into the extracellular fluid. Hormones are transported primarily via the bloodstream throughout the body, where they bind to receptors on target cells, inducing a characteristic response. As a result, endocrine signaling requires more time than neural signaling to prompt a response in target cells, although the precise amount of time varies with different hormones.

EXAMPLE

The hormones released when you are confronted with a dangerous or frightening situation, called the fight-or-flight response, occur by the release of adrenal hormones—epinephrine and norepinephrine—within seconds. In contrast, it may take up to 48 hours for target cells to respond to certain reproductive hormones.In addition, endocrine signaling is typically less specific than neural signaling. The same hormone may play a role in a variety of different physiological processes, depending on the target cells involved.

EXAMPLE

The hormone oxytocin promotes uterine contractions in people in labor. It is also important in breastfeeding and may be involved in the sexual response and in feelings of emotional attachment in humans.In general, the nervous system involves quick responses to rapid changes in the external environment, and the endocrine system is usually slower acting—taking care of the internal environment of the body, maintaining homeostasis, and controlling reproduction.

So how does the fight-or-flight response that was mentioned earlier happen so quickly if hormones are usually slower acting? It is because the two systems are connected. It is the fast action of the nervous system in response to the danger in the environment that stimulates the adrenal glands to secrete their hormones. As a result, the nervous system can cause rapid endocrine responses to keep up with sudden changes in both the external and internal environments when necessary.

| Types of Signaling in the Endocrine and Nervous Systems | ||

|---|---|---|

| Endocrine system | Nervous system | |

| Signaling mechanism(s) | Chemical | Chemical/electrical |

| Primary chemical signal | Hormones | Neurotransmitters |

| Distance traveled | Long or short | Always short |

| Response time | Fast or slow | Always fast |

| Environment targeted | Internal | Internal and external |

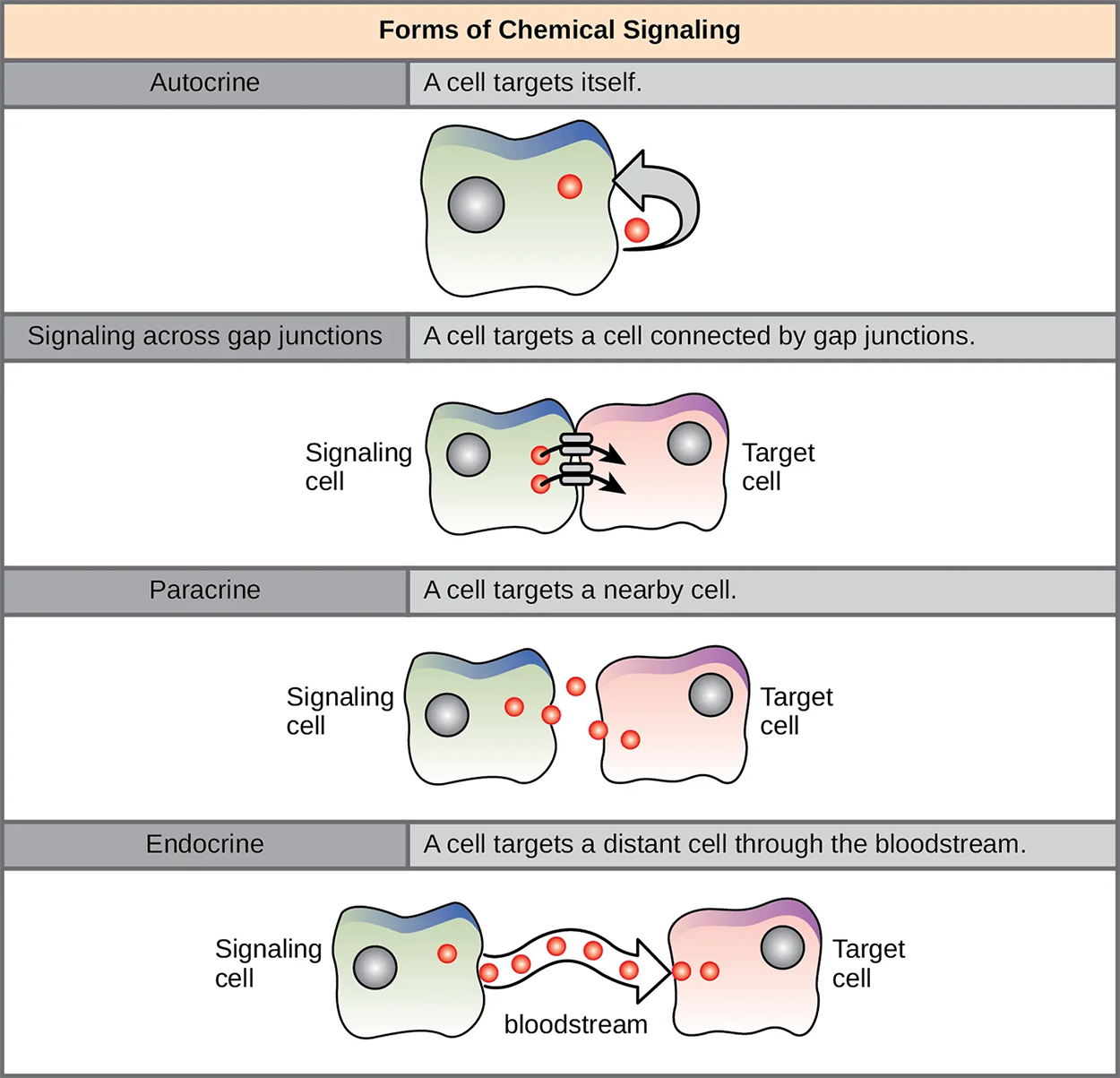

The main difference between the different types of chemical signaling is the distance that the signal travels through the organism to reach the target cell.

In endocrine signaling, hormones secreted into the extracellular fluid diffuse into the blood or lymph and can then travel great distances throughout the body. In contrast, autocrine signaling takes place within the same cell. An autocrine (auto, self) is a chemical that elicits a response in the same cell that secreted it.

EXAMPLE

Interleukin-1, or IL-1, is a signaling molecule that plays an important role in inflammatory response. The cells that secrete IL-1 have receptors on their cell surface that bind these molecules, resulting in autocrine signaling.Direct signaling occurs by gap junctions, which are connections between the plasma membranes of neighboring cells, in animals and plasmodesmata in plants. These fluid-filled channels allow small signaling molecules, called intracellular mediators, to diffuse between the two cells. Small molecules or ions, such as calcium ions (Ca²⁺), are able to move between cells, but large molecules like proteins and DNA cannot fit through the channels.

The specificity of the channels ensures that the cells remain independent but can quickly and easily transmit signals. The transfer of signaling molecules communicates the current state of the cell that is directly next to the target cell; this allows a group of cells to coordinate their response to a signal that only one of them may have received.

Local intercellular communication also occurs by paracrine signaling. A paracrine, also called a paracrine factor, is a chemical that induces a response in neighboring cells. Although paracrines may enter the bloodstream, their concentration is generally too low to elicit a response from distant tissues.

EXAMPLE

A familiar example to those with asthma is histamine, a paracrine that is released by immune cells in the bronchial tree. Histamine causes the smooth muscle cells of the bronchi to constrict, narrowing the airways. Another example is the neurotransmitters of the nervous system, which act only locally within the synaptic cleft.

Hormones cause changes in target cells by binding to specific cell surface or intracellular hormone receptors, which are molecules embedded in the cell membrane or floating in the cytoplasm with a binding site that matches a binding site on the hormone molecule. In this way, even though hormones circulate throughout the body and come into contact with many different cell types, they only affect cells that possess the necessary receptors.

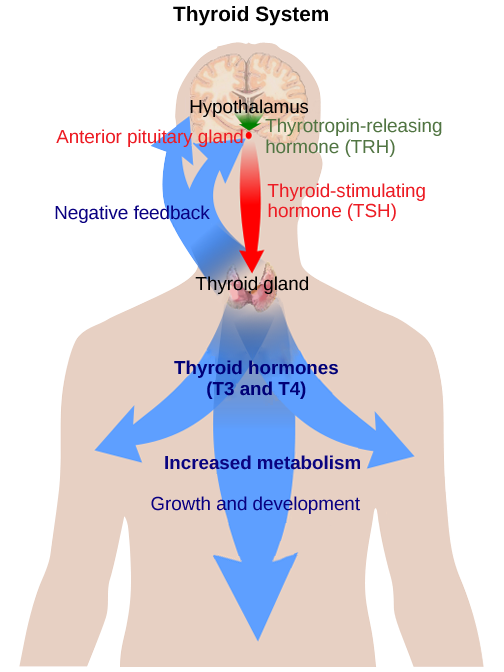

Receptors for a specific hormone may be found on or in many different cells or may be limited to a small number of specialized cells. For example, thyroid hormones act on many different tissue types, stimulating metabolic activity throughout the body. Cells can have many receptors for the same hormone but often also possess receptors for different types of hormones. The number of receptors that respond to a hormone determines the cell’s sensitivity to that hormone, and the resulting cellular response.

Additionally, the number of receptors available to respond to a hormone can change over time, resulting in increased or decreased cell sensitivity. In upregulation, the number of receptors increases in response to rising hormone levels, making the cell more sensitive to the hormone and allowing for more cellular activity. When the number of receptors decreases in response to rising hormone levels, called downregulation, cellular activity is reduced.

The contribution of feedback loops to homeostasis, which you previously learned about, will only be briefly reviewed here. Positive feedback loops are characterized by the release of additional hormones in response to an original hormone release. The release of oxytocin during childbirth is a positive feedback loop. The initial release of oxytocin begins to signal the uterine muscles to contract, which pushes the fetus toward the cervix, causing it to stretch. This, in turn, signals the pituitary gland to release more oxytocin, causing labor contractions to intensify. The release of oxytocin decreases after the birth of the child.

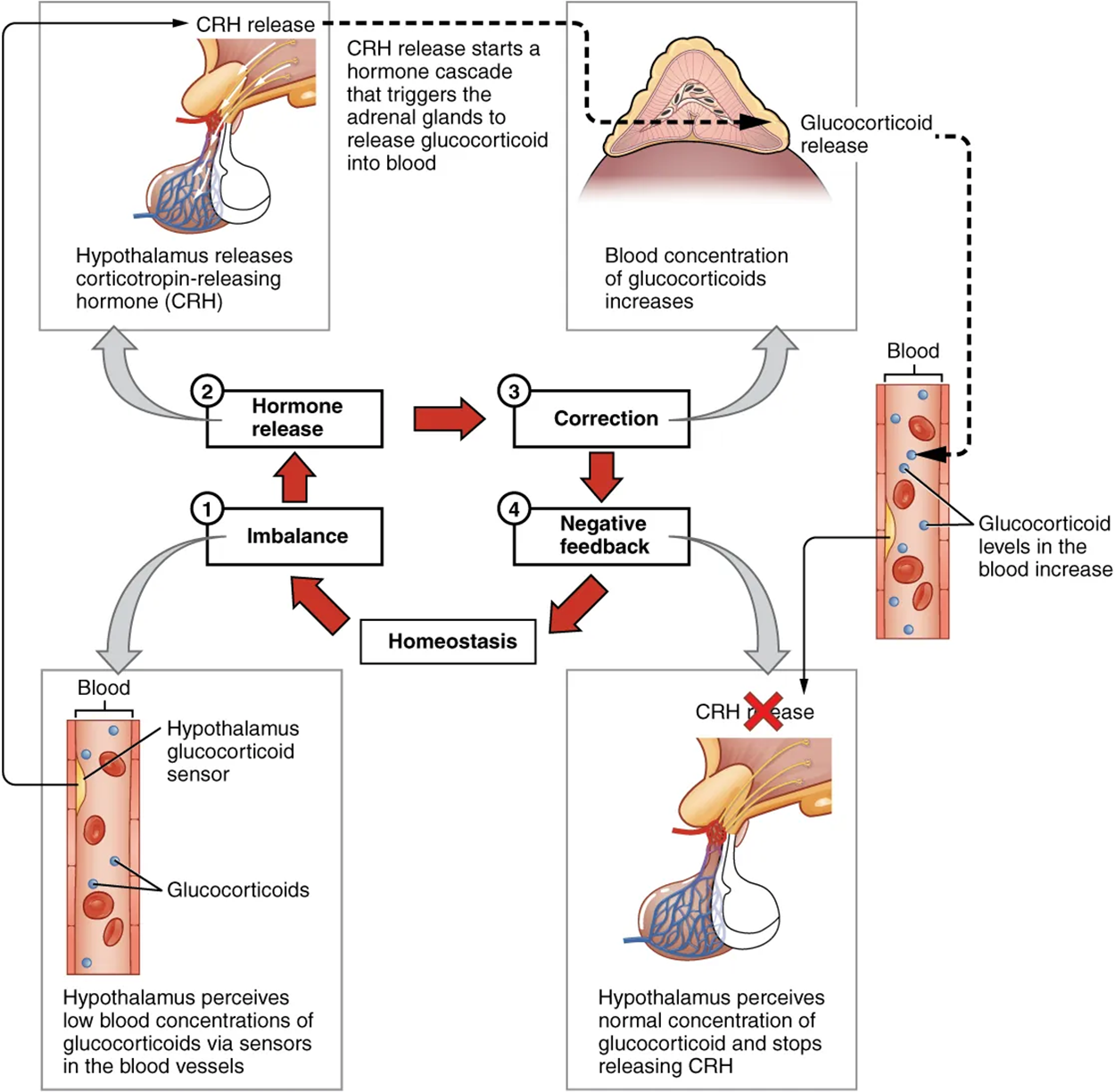

The more common method of hormone regulation is the negative feedback loop. Negative feedback is characterized by the inhibition of further secretion of a hormone in response to adequate levels of that hormone. This allows blood levels of the hormone to be regulated within a narrow range. An example of a negative feedback loop is the release of glucocorticoid hormones from the adrenal glands, as directed by the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. As glucocorticoid concentrations in the blood rise, the hypothalamus and pituitary gland reduce their signaling to the adrenal glands to prevent additional glucocorticoid secretion.

Another example is the anterior pituitary signaling the thyroid to release thyroid hormones. Increasing levels of these hormones in the blood then give feedback to the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary to inhibit further signaling to the thyroid gland.

Hormones can actually interact with each other to produce different effects.

One type of hormone interaction is an opposing interaction (also known as an antagonistic interaction), where the effect of one hormone opposes the effect of another.

EXAMPLE

Examples of opposing hormone interactions are insulin and glucagon. Insulin is a type of hormone that helps to lower sugar levels, while glucagon is a type of hormone that helps to increase blood sugar levels. There are certain situations when these hormones need to be released, such as after a meal (insulin) or when starved (glucagon), but not at the same time.Sometimes hormones can create synergistic interactions, which means the two hormones cooperate with each other to affect a target cell. The overall effect is greater in cooperation than individually.

A permissive interaction is when one hormone will prepare a cell for another hormone. For the second hormone to be able to affect the target cell, the target cell first has to be exposed to the first hormone. Think of it as one hormone will prep the cell for the other hormone to be able to take effect. The second hormone does not take effect until the cell has been exposed to the first hormone.

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM (1) OPENSTAX “BIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/BIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION (2) OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSING (1 & 2): CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.