Table of Contents |

Recall that humoral response is the half of adaptive immunity that involves B cells producing antibodies. Some of these (like IgA and IgG) are secreted so they can float around the lymph. When they encounter a pathogen with the unique antigen they recognize, they can bind the pathogen and cause agglutination, for example, so the pathogen clumps instead of infecting our cells.

The antibodies that B cells produce can't enter a cell, so they can't combat a pathogen once that pathogen has infected one of our cells.

So then how does our body fight infection once it has entered our cells? Cell-mediated immunity is a response taken against a threat that has entered a cell.

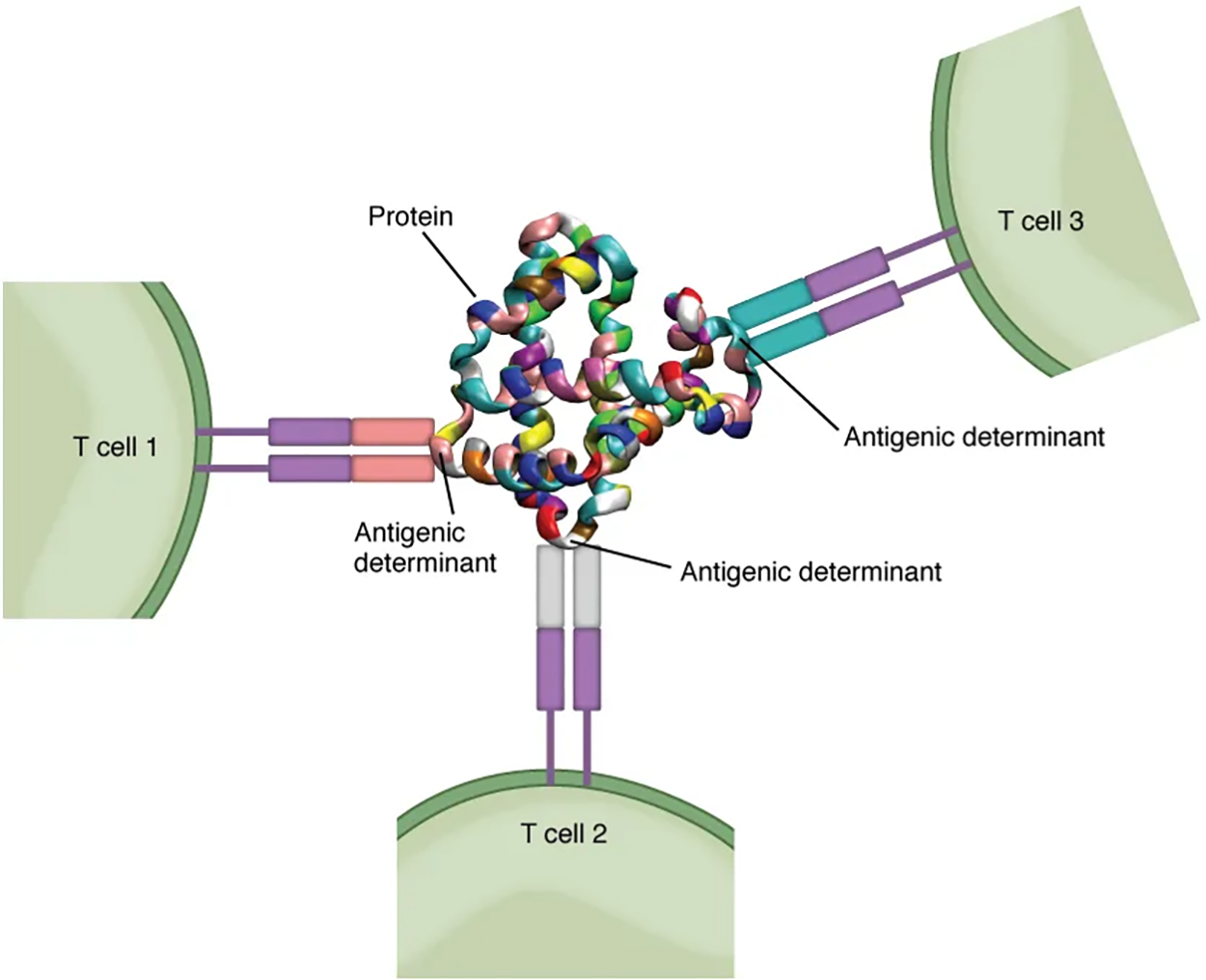

Recall that antigens are the small chemical groups often associated with pathogens that are recognized by receptors on the surface of B and T lymphocytes. Antigens on pathogens are usually large and complex, and they consist of many antigenic determinants.

An antigenic determinant (epitope) is one of the small regions within an antigen to which a receptor can bind, and antigenic determinants are limited by the size of the receptor itself. They usually consist of six or fewer amino acid residues in a protein, or one or two sugar moieties in a carbohydrate antigen.

Antigenic determinants on a carbohydrate antigen are usually less diverse than on a protein antigen. Carbohydrate antigens are found on bacterial cell walls and on red blood cells (the ABO blood group antigens). Protein antigens are complex because of the variety of three-dimensional shapes that proteins can assume, and they are especially important for the immune responses to viruses and worm parasites. It is the interaction of the shape of the antigen and the complementary shape of the amino acids of the antigen-binding site that accounts for the chemical basis of specificity.

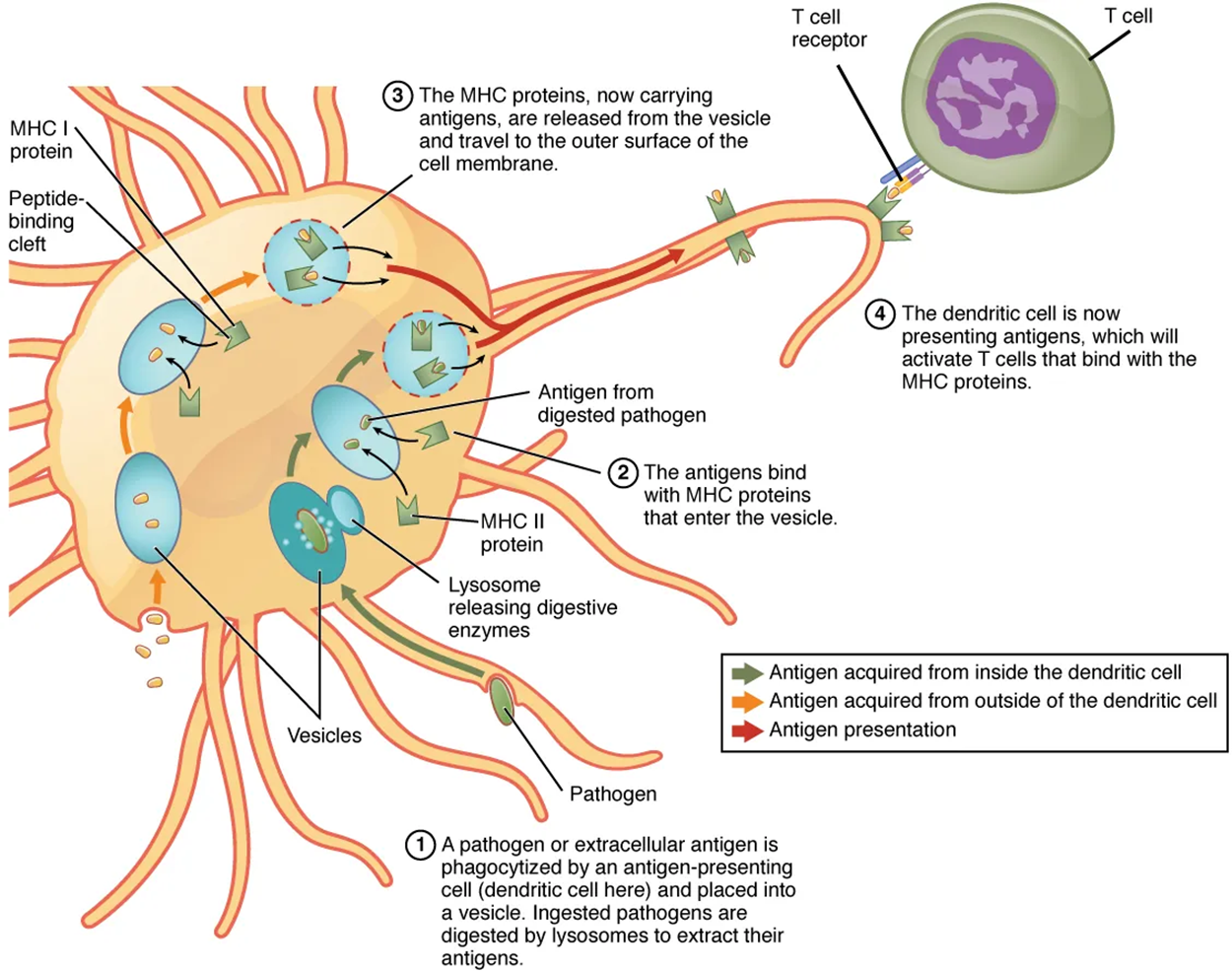

T cells do not recognize free-floating or cell-bound antigens as they appear on the surface of the pathogen. They only recognize antigens on the surface of specialized cells called antigen-presenting cells. Antigens are internalized by these cells. Antigen processing is a mechanism that enzymatically cleaves the antigen into smaller pieces. The antigen fragments are then brought to the cell’s surface and associated with a specialized type of antigen-presenting protein known as a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecule.

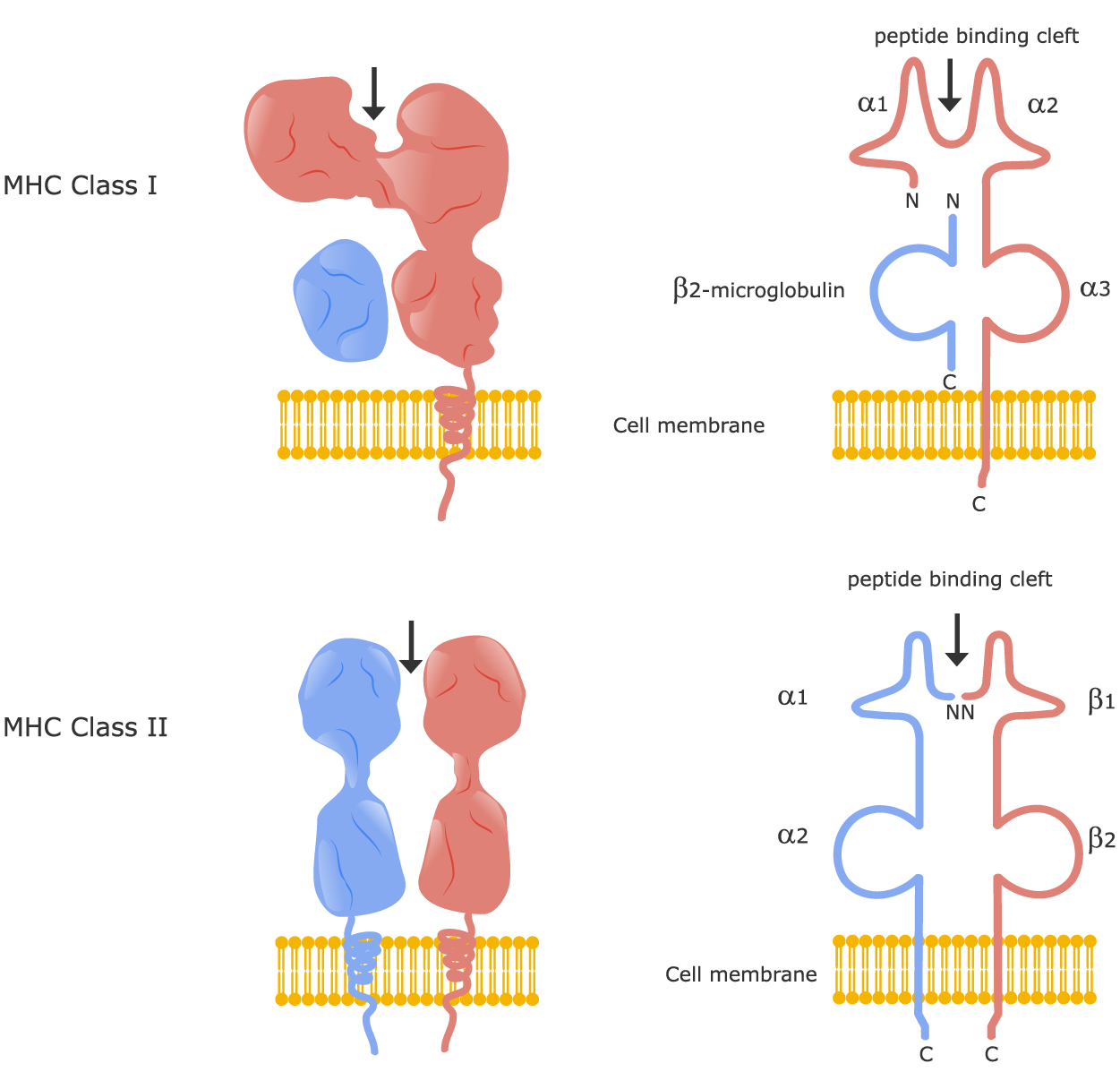

The MHC is the cluster of genes that encode these antigen-presenting molecules. The association of the antigen fragments with an MHC molecule on the surface of a cell is known as antigen presentation and results in the recognition of antigen by a T cell. This association of antigen and MHC occurs inside the cell, and it is the complex of the two that is brought to the surface. The peptide-binding cleft is a small indentation at the end of the MHC molecule that is farthest away from the cell membrane; it is here that the processed fragment of antigen sits. MHC molecules are capable of presenting a variety of antigens, depending on the amino acid sequence, in their peptide-binding clefts.It is the combination of the MHC molecule and the fragment of the original peptide or carbohydrate that is actually physically recognized by the T cell receptor (TCR).

Each TCR consists of two polypeptide chains that span the T cell membrane; the chains are linked by a disulfide bridge. Each polypeptide chain is comprised of a constant domain and a variable domain: a domain, in this sense, is a specific region of a protein that may be regulatory or structural. The intracellular domain is involved in intracellular signaling. A single T cell will express thousands of identical copies of one specific TCR variant on its cell surface.

The specificity of the adaptive immune system occurs because it synthesizes millions of different T cell populations, each expressing a TCR that differs in its variable domain. This allows recognition of various antigens, such as pathogens and cancer cells. The binding between an antigen-displaying MHC molecule and a complementary TCR “match” indicates that the adaptive immune system needs to activate and produce that specific T cell because its structure is appropriate to recognize and destroy the invading pathogen.

Two distinct types of MHC molecules, MHC class I and MHC class II, play roles in antigen presentation. Although produced from different genes, they both have similar functions. They bring processed antigen to the surface of the cell via a transport vesicle and present the antigen to the T cell and its receptor. Antigens from different classes of pathogens, however, use different MHC classes and take different routes through the cell to get to the surface for presentation. The basic mechanism, though, is the same.

Antigens are processed by digestion, are brought into the endomembrane system of the cell, and then are expressed on the surface of the antigen-presenting cell for antigen recognition by a T cell. Intracellular antigens are typical of viruses, which replicate inside the cell, and certain other intracellular parasites and bacteria. These antigens are processed in the cytosol by an enzyme complex known as the proteasome and are then brought into the endoplasmic reticulum by the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) system, where they interact with MHC class I molecules and are eventually transported to the cell surface by a transport vesicle.

Extracellular antigens, characteristic of many bacteria, parasites, and fungi that do not replicate inside the cell’s cytoplasm, are brought into the endomembrane system of the cell by receptor-mediated endocytosis. The resulting vesicle fuses with vesicles from the Golgi complex, which contain preformed MHC class II molecules. After fusion of these two vesicles and the association of antigen and MHC, the new vesicle makes its way to the cell surface.

Many cell types express class I molecules for the presentation of intracellular antigens. These MHC molecules may then stimulate a cytotoxic T cell immune response, eventually destroying the cell and the pathogen within. This is especially important when it comes to the most common class of intracellular pathogens, the virus. Viruses infect nearly every tissue of the body, so it is necessary that all these tissues be able to express MHC class I molecules, or no T cell response can be made.

On the other hand, MHC class II molecules are expressed only in the cells of the immune system, specifically cells that affect other arms of the immune response. Thus, these cells are called “professional” antigen-presenting cells to distinguish them from those that bear MHC class I molecules. The three types of professional antigen presenters are macrophages, dendritic cells, and B cells (see the table below).

Macrophages stimulate T cells to release cytokines that enhance phagocytosis. Dendritic cells also kill pathogens by phagocytosis (see the figure “Antigen Processing and Presentation” presented earlier), but their major function is to bring antigens to regional draining lymph nodes. The lymph nodes are the locations in which most T cell responses against pathogens of the interstitial tissues are mounted. Macrophages are found in the skin and in the lining of mucosal surfaces, such as the nasopharynx, stomach, lungs, and intestines. B cells may also present antigens to T cells, which are necessary for certain types of antibody responses.

| Classes of Antigen-Presenting Cells | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MHC | Cell type | Phagocytic? | Function |

| Class I | Many | No | Stimulates cytotoxic T cell immune response |

| Class II | Macrophage | Yes | Stimulates phagocytosis and presentation at primary infection site |

| Class II | Dendritic | Yes, in tissues | Brings antigens to regional lymph nodes |

| Class II | B cell | Yes, internalizes surface immunoglobulin and antigen | Stimulates antibody secretion by B cells |

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM (1) OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. (2) OPENSTAX “MICROBIOLOGY”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/MICROBIOLOGY/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSING (1 & 2): CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.