Table of Contents |

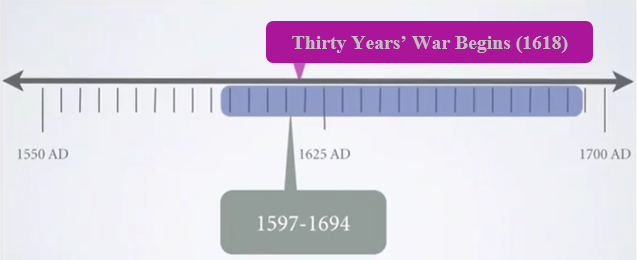

The frescoes that you will be looking at today date from between 1597 to 1694, covering almost 100 years, and focus geographically on Italy.

Ceiling frescoes are an interesting subcategory of work. They aren’t any different than regular frescoes, at least in terms of how they’re made. Stylistically, however, artists use the unique perspective offered by ceiling frescoes in truly innovative ways, creating a sense of awe and wonder in the buildings where these paintings reside.

Annibale Carracci originated from Rome. His work, titled “The Loves of the Gods,” was a series of frescoes painted on the ceiling and upper walls of the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. As the name indicates, the fresco depicts images from the Greek and Roman mythology of gods and the women they loved.

1597

Fresco

The fresco features mythological couples such as Perseus and Andromeda. Below, Perseus can be seen on Pegasus, about to turn the Kraken to stone with Medusa’s severed head.

Another featured couple is Jupiter and Juno, shown below.

A final example is the image of the triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne.

Carracci’s style recalls Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes, as well as the colors of Titian. His use of illusionism—in particular the painted frames that set the images apart from each other—is indicative of a stylistic element that was pervasive in the ceiling frescoes of the 17th century.

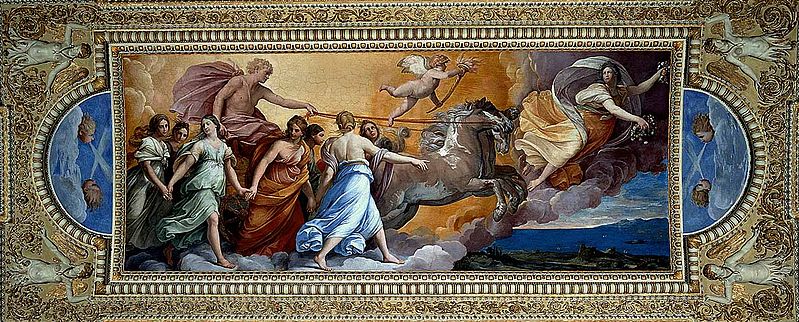

Guido Reni trained in the same Bologna art academy as Carracci. In a fashion similar to his contemporary’s work, Guido’s “Aurora” is surrounded by a very convincing, albeit painted, frame. It depicts Aurora leading Dawn (in the chariot) and his entourage across the sky, bringing forth a new day.

1614

Fresco

Here are closeups of both Dawn and his entourage:

This artist shows influence from classical Roman triumphal processions, as well as from Renaissance masters, such as Raphael, in his depiction of forms.

No stranger to elaborate depictions glorifying his family, Pope Urban VIII commissioned the ceiling fresco seen below by the artist Pietro da Cortona as a way of commemorating his family and ensuring their legacy in the hearts and minds of the people. It’s an amazing example of the “as seen from below” technique in which the ceiling appears to be blown through the roof, revealing Divine Providence with the halo, directing Immortality, who is placing a crown of stars that symbolize eternal life on the Barberini family.

1633-1639

Fresco

Here is a closer visual of Divine Providence:

The personifications of hope, charity, and faith are holding a wreath that encircles three bees, the symbol of the Barberini family, in the center. This symbol can also be seen on the St. Peter’s baldacchino from Bernini—also commissioned by Pope Urban VIII.

Paintings such as the ceiling fresco “Triumph in the Name of Jesus,” by Giovanni Battista Gaulli, are considered extremely important by the Catholic Church. Whereas the Protestant Church, in many cases, prohibited the use of artwork in churches, the Catholic Church—via the influence of the Counter-Reformation—saw these highly dramatic works of art as vital forms of persuasive religious imagery, examples that would encourage faith and religious conversion.

Just as with Cortona’s fresco, the ceiling appears to be blown through the roof, revealing the golden light of heaven shining down.

1674-1679

Fresco

The artistry exhibited is truly remarkable. The painting is so well integrated with the architecture that it’s almost impossible to tell what’s real and what’s painted. It is an excellent example of trompe l’oeil.

Christ is represented by the monogram “IHS” beneath a cross, but it is almost invisible due to the backdrop of blinding light from heaven, which contrasts with the dark shadow of sinners falling back to Earth.

One of the finest examples of trompe l’oeil is the ceiling fresco “Glorification of St. Ignatius,” painted by Jesuit monk, Andrea Pozzo.

1685-1694

Fresco

Pozzo extends the architecture of the church through painting, creating the impression of tremendous verticality that opens upward towards heaven, in the figure of Christ with St. Ignatius rising toward his savior.

Again, it’s almost impossible to tell where the real architecture ends and the painting begins, creating a truly awe-inspiring sensation and tremendously spiritual moment for the pious observer below.

Here’s another view of the architecture extending and creating that sense of verticality:

Source: This work is adapted from Sophia author Ian McConnell.