Table of Contents |

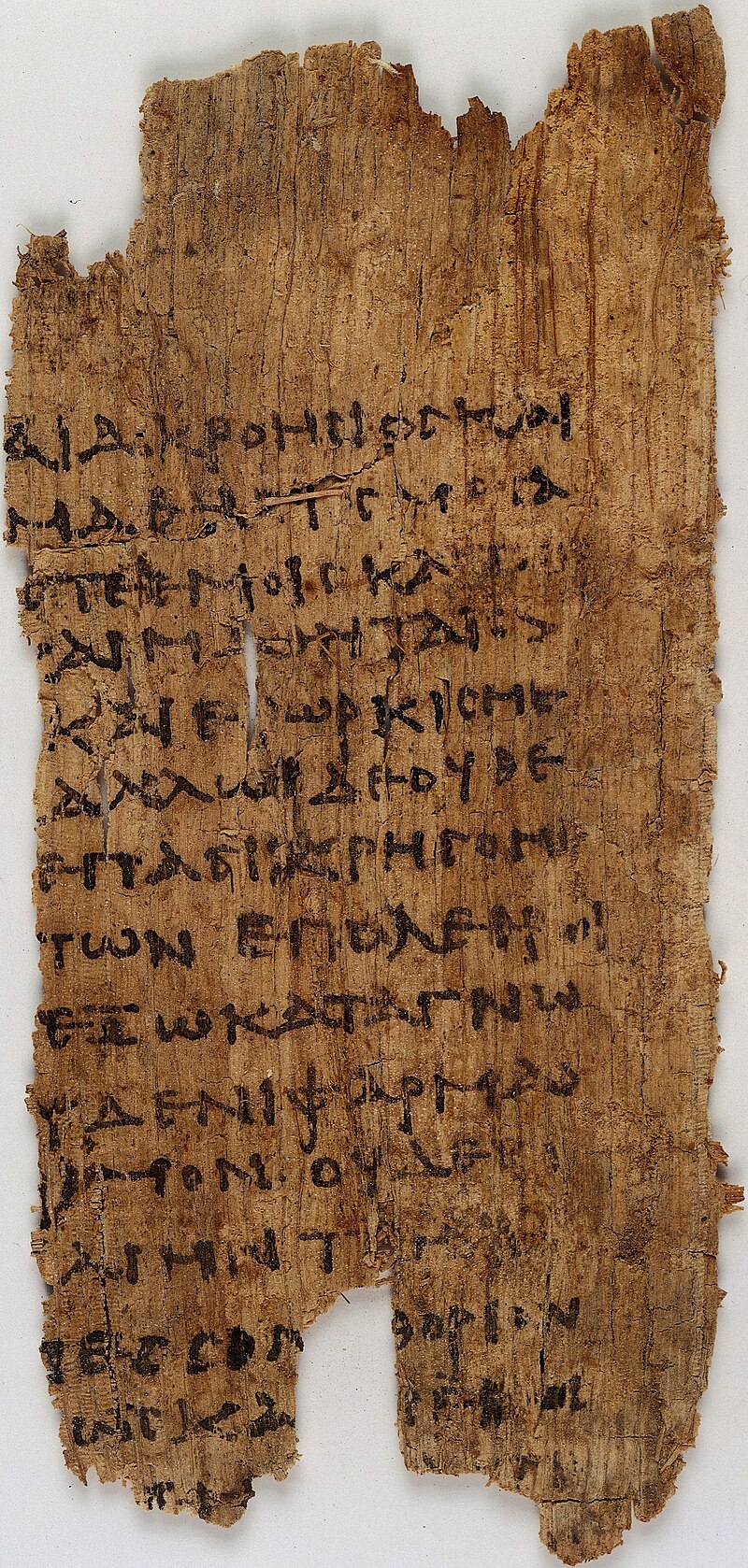

One of the oldest codes of professional ethics is the Hippocratic Oath. It was written over time between the 5th and 3rd century BCE by the members of a secret society in Ancient Greece who attempted to follow the lessons of Pythagoras. The oath was not written by Hippocrates, but by his followers.

The Pythagoreans had many different interests, but a major one was the practice of medicine as developed by Hippocrates. In this oath, we find many aspects that would be familiar to contemporary physicians: Keeping patient information secret, acting out of concern for the patient, and not taking actions outside of the doctor’s skillset.

It is common to hear people referring to the Hippocratic Oath as the source of the phrase “first, do no harm” that is thought to be key to medical ethics. However, that phrase does not come from the oath. There are conflicting accounts of its origin, but whether we trace it to 17th century British physician Thomas Sydenham or 19th century French physician August Chomel, the command and phrasing comes much later than the Hippocratic Oath’s Greek roots. The oath itself is an interesting mix of a deontological and virtue ethics approach.

EXAMPLE

There is a prohibition from giving an overdose of medication in order to cause a patient’s death. This rule-based understanding is in keeping with deontology. However, the oath ends with a statement that if the physician follows the oath they will be remembered and praised by others, and if they break the oath the “opposite of this” will happen. This focus on how one’s lifetime of actions will be seen by others is in keeping with an understanding of morality consistent with Aristotle’s virtue ethics.In the time since the Hippocratic Oath was written, multiple different statements or codes of ethics have been written. Many of them have strong links to the place and time in which they are written. Thus, we see a change from the Hippocratic Oath forbidding physicians to have sex with a patient’s slaves, to the 19th century Percival Code from England, which includes extensive discussion about how to resolve conflicts between staff members. These conflicts began to be more common after the growth of hospitals due to the typhus epidemic at the end of the 18th century.

Today we can find multiple codes, including the American Medical Association’s Code of Medical Ethics (first written in 1847), the Florence Nightengale Pledge (1893), the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Geneva (1948), and more. After World War II and various ethics scandals in medicine in the 1960s and early 1970s, more attention became focused on developing an appreciation in medical school training of ethics in medicine.

By the late 1970s, two foundational texts had emerged: the “Belmont Report,” which provided guidance for medical research on human subjects, and Principles of Biomedical Ethics, by Tom Beauchamp (pronounced Beech-am) and James Childress. In Beauchamp and Childress’s book they outlined an ethical approach to broader medical interactions, including not only research but also patient care, structures of insurance, and more. Both texts use an approach to ethics called principalism. This approach attempts to capture a “common morality” of multiple considerations involved in ethical decisions; rather than engage in abstract debate, they lay out commonly agreed on ethical principals that guide decisions.

Unlike deontology, these principalist approaches accepted that something relevant to moral decision making in one situation might not always be the most important thing. Whether the Belmont Report’s three principles, or Beauchamp and Childress’s four principles, each aspect points to items which are relevant to determining the right thing to do.

The wording of the principles has changed over time, but the most recent version of Beauchamp and Childress’s principles are:

EXAMPLE

Someone living in a smaller rural town will have less access to medical care than someone living in a large urban city. By thinking about justice, we can evaluate if the difference in access is significant enough to be ethically relevant when considering something like where public health funds are to be spent.Since principalism became dominant, we have seen many changes in routine medical care. Patients now know the diagnosis of their illnesses, the names of medications prescribed to them, the risks of surgeries, and more. The framework of justice has encouraged discussions about health insurance systems, costs of medications, access to experimental medicine, etc.

Perhaps the most visible application of justice concerns occurs when discussing what is termed “allocation of scare resources.” One example of this is to think about organ transplantation. As of this writing, there are approximately 3,800 people in the United States waiting for a heart transplant. There are a number of factors that can impact if the transplant will be successful, including the size of the heart, the blood type of the donor, and how far the heart would have to travel after being harvested. Weighing all of these factors involves a discussion about what would be the most just method of distributing the hearts. Sometimes patients and their families become angry that they are waiting for a transplant, but the system is built to provide the most just outcome, even if that is not the easiest outcome.

Before we consider some of the different ethical approaches to the issue of genetic screening, we should be clear about what exactly we mean by this term. Genetic screening is the use of prenatal exams to decide whether or not to terminate a pregnancy, usually because the exams show the fetus has inherited a disability or severe medical condition.

Genetic screening, particularly pre-implantation genetic screening, is one of many technologies within reproductive ethics where we can take unprecedented control over reproduction. It’s controversial in large part because it:

EXAMPLE

Jamar and his partner Tony want their friend Sarah to act as a surrogate for their baby. The couple is very confident in choosing their friend Sarah but would like her to undergo genetic screening so they know about any potential genetic disabilities the child may inherit. Sarah is hesitant due to concerns about her health privacy and wants any embryo to be naturally selected without screening. Now, Jamar and Tony are concerned about their reproductive liberty.In this example, ethics are involved in both the couple's and the surrogate’s interests. Jamar and Tony want to exercise their freedom to choose their potential surrogate and know any genetic factors she may pass on to their child. The potential surrogate, Sarah, also has a right to decline due to the proposed process no longer fitting her moral needs. Both groups (Jamar/Tony and Sarah) can be said to be operating in keeping with their own interests and desires.

Based on the principle of respect for autonomy, Sarah can refuse to allow her eggs to be used if they were screened. Jamar and Tony can also rely upon a respect for autonomy to require that any embryo implanted be first screened for known genetic abnormalities. We even could consider if the fertility clinic ought to consider what wishes the potential person that the implanted embryo represents might have interests. The embryo cannot engage in informed consent (knowing and agreeing to a medical process) but there is an open question as to if Jamar/Tony or Sarah ought to be used to provide proxy consent (the substitute for giving consent when the person receiving the treatment cannot).

There are several ethical factors at play, but let’s focus on the genetic screening factor. In this instance, genetic screening can be controversial due to the human will to select specific embryos over others instead of natural random selection without human interference.

Many diseases are known to be at least partly genetic (like cystic fibrosis, Tay-Sachs, cerebral palsy, or certain forms of muscular dystrophy), and scientists have identified the genes that cause the diseases. Many forms of genetic screening thus attempt to identify embryos with these genetic differences and bypass implanting those embryos. Parents who know they have a high probability of passing on genetic defects may run tests early in their pregnancy and terminate a pregnancy when they know the baby will have a serious condition that can shorten their life considerably and present numerous challenges.

While such awareness of genetic differences can be considered morally permissible, what happens with that information brings up the question of ethics, especially in regard to disability rights and diversity in populations. Therefore, the most important issue for determining the permissibility of genetic screening in pre-implantation is deciding whether or not a fetus counts as a human.

When individuals are not able to provide their own consent, either because they are currently incompetent, too young to make rational decisions, or because of a mental condition are unable to understand the risks of a medical procedure, another individual can provide consent in their place. This is known as proxy consent. These proxies can be assigned by the courts, be named through documents like a power of attorney, or be understood through formal relationships.

EXAMPLE

Parents use proxy consent rights to make decisions for their minor children. A spouse might use proxy consent to agree to a surgery for a presently unconscious husband. Adult children might use proxy consent to decide about care for their parent with dementia.As previously mentioned, genetic screening provides potential parents with insight into genetic conditions an embryo may carry. Further, genetic screening could in principle screen for any trait that is, at least partially, an inherited trait whether or not it is associated with the health of the embryo.

EXAMPLE

Couples could even use genetic testing to select the sex of the child they want.These types of decisions based on inherited traits could lead to a less diverse human population and questions of personal morals across society. Some people think genetic screening is wrong because it penalizes disability and privileges some human traits over others.

Others think genetic screening is fine because it would be the same as aborting after discovering a fetal abnormality, a defective embryo unlikely to survive to term, or because it’s wrong to bring a child into the world one knows will have a disability when this could easily be prevented.

Now, let’s see how different ethical verdicts could be produced through different ethical frameworks. First, consider genetic screening from the perspective of virtue-based ethics. Recall that virtue-based ethics evaluates actions in terms of what kind of character they manifest and how such actions could, in turn, inform our character.

With this in mind, you can see that it depends on what kind of character the person reveals in their action.

EXAMPLE

If someone does genetic screening to find out whether an embryo is nonviable, the virtue ethicist would consider that acceptable because screening is saving a future child from suffering and the birthing person from a potentially dangerous pregnancy. But if they do it simply because the child would have profound disabilities, though the embryo is still viable, then the virtue ethicist would consider this morally unacceptable as it privileges an able-bodied life over a disabled one.As you can see, virtue-based ethics will say something is permissible if it manifests virtues, but impermissible if it manifests vices.

Now, let’s see how a utilitarian would evaluate genetic screening. A utilitarian would say that whether genetic screening is acceptable or not depends upon the consequences of genetic screening. Since the primary consequence of genetic screening is the discarding of embryos, and this is a morally neutral act as embryos are not fetuses and, further, are not children, utilitarianism would label genetic screening morally acceptable.

A Kantian deontologist would have to determine if genetic screening would violate the categorical imperative. To determine this, they would consider if the maxim they are considering could be universalized. What if everyone screened for genetic differences? This might result in an end to genetically linked illnesses like Huntington’s Disease, but could result in terminating pregnancies with other physical features – like being unusually short – that are not medical conditions. They could even extend to mere preferences, such as selecting the child’s sex, or which parent they want the baby to look like. The Kantian deontologist would thus likely have the categorical imperative of not using genetic screening for any reason.

For the principalist, a major concern might come by considering the principle of justice. Who has access to genetic screening? Could regularizing testing result in a group of privileged people who are “genetically healthier” than those who are born through unassisted reproduction (i.e. unprotected sex)? Is this potential disparity morally problematic?