Table of Contents |

The artwork that you will be looking at today comes from 1600 to 1640 and focuses geographically on Milan, now in modern-day Italy, where Caravaggio originates.

If the stories are true, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was a veritable “bad boy” of the artistic world. He was reportedly known as much for his temper, bad mood, and disdain for the classical artists that preceded him as he was for his artistic genius. Evidently, he was prone to fighting and trashing his apartment in Milan, Italy.

Despite his temperament, his influence and talent were unquestionable, particularly his use of light and perspective to enhance the drama of his work, giving it a theatrical quality that was entirely unique at the time. Caravaggio’s career was short-lived, its greatest years extending only from 1600 until his somewhat mysterious death in 1610 at the age of 38. He was an intense figure who burned out quickly. But he was highly influential to a number of artists that came after him, even if he was largely forgotten by the rest until hundreds of years later.

This first image by Caravaggio is of the “Calling of Saint Matthew”, and it’s a great example of Caravaggio’s unique style. He was known for incorporating the setting in which his paintings would be located, and this particular painting is actually set in the room of an Italian inn from Caravaggio’s time.

1600

Oil on canvas

Christ is the figure on the far right, almost hidden in the shadows, pointing at the figure of Levi, the tax collector, who became Matthew. Levi, in the same instant, is pointing to himself in seeming disbelief. Christ’s gesture is reminiscent of the depiction of Adam’s gesture in Michelangelo’s ceiling fresco in the Sistine Chapel.

The use of chiaroscuro is clearly evident, but Caravaggio’s innovation of using a single source of light to illuminate Levi—thereby lending a theatrical or stage-like quality to his art—is one of the most notable qualities of his work. This technique is called tenebrism, and is employed not only by Caravaggio, but also by his followers, called Caravaggisti.

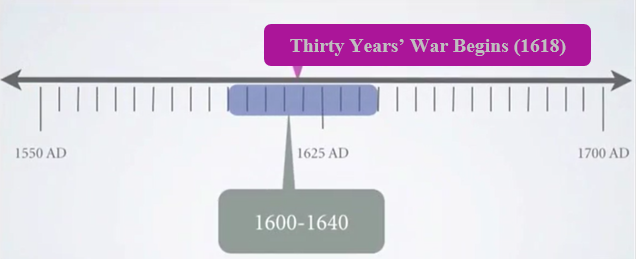

Caravaggio has two paintings attributed to him concerning the conversion of Saint Paul. The first, seen below, is the earlier work, by at least a year. It is often considered to be a more Mannerist than Baroque interpretation of the story. Saint Paul, covering his eyes, is just one of a collection of characters in this particular scene.

.jpg)

1600

Oil on wood

It’s difficult to tell at first glance, but the figure of Christ is being held by an angel near the top right of the scene, and is creating a vision that overwhelms the figure of Saint Paul, which is why he’s covering his eyes.

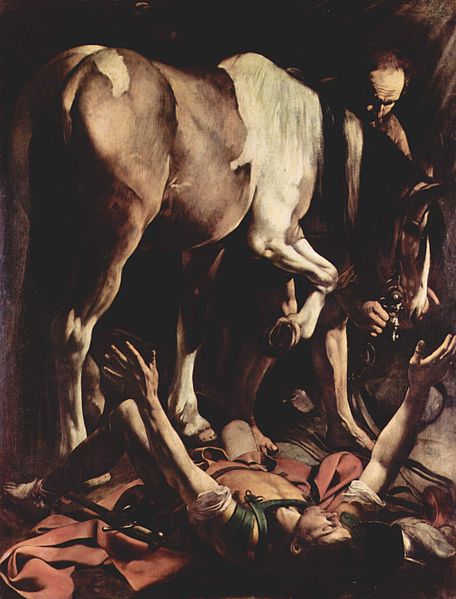

The next image, also called the “Conversion of St. Paul”, or the “Conversion of St. Paul on the Way to Damascus”, is considered to be a much more characteristic example of Caravaggio’s work. It depicts the figure of Saint Paul lying on his back, apparently having fallen off his horse in the midst of a vision from Christ.

1601

Oil on canvas

Again, Caravaggio uses a single source of light to illuminate the scene, and Saint Paul is dressed in clothing that would have been familiar to people at the time. Caravaggio utilizes a rather low point of perspective, taking into account the position of viewers, making them feel as if they’re part of the scene, standing at the head of Saint Paul.

Caravaggio’s “Entombment,” shown below, again makes use of a rather low horizon, pulling the viewer in, and forcing the action to take place in the foreground.

1603

Oil on canvas

There are no idealizations of his subjects. They agonize and struggle with the weight of the body of Christ (see closeup below), which is interestingly devoid of any signs of trauma, and about to be set on the stone slab in front of the viewer. Caravaggio uses emotion, lighting, and the theatrical depiction of his subjects to generate the emotional connection, rather than the gruesome depiction of a tortured body.

As mentioned before, Caravaggio’s followers were known as Caravaggisti. One of them, Artemisia Gentileschi, is an important artist to discuss, not just because of her talent, but because of her gender. In a male-dominated world, Gentileschi’s talent stands out as some of the best from this period.

Her painting of “Judith Beheading Holofernes” is typical of her desire to paint subjects with strong female characters. It’s a particularly graphic and gruesome rendition of the biblical story. Judith was a beautiful Jewish widow who seduced the Babylonian general Holofernes of the invading Babylonian army and beheaded him while he was drunk, taking his head back to her people as a means of rallying the Hebrews to victory.

1611-1612

Oil on canvas

The influence of Caravaggio is undeniable, particularly in the use of a low horizon pushing the action to the foreground, as well as the use of a single light source to illuminate the scene. This is inspired, undoubtedly, by the treatment of the same subject matter by Caravaggio himself in his painting from 1599, shown below.

1599

Oil on canvas

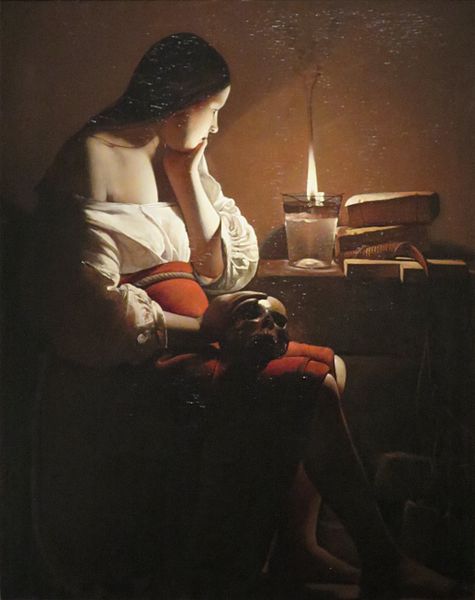

Georges de la Tour was a French Baroque painter who showed influence from Caravaggio, particularly in his application of chiaroscuro and use of a single light source. However, his departure comes from the fact that you can actually see the source of light. This changes the overall mood of the painting from the theatrical, like you'd see with Caravaggio, to something intimate and private that you’re looking in on.

In this example, called “Magdalen With the Smoking Flame,” the viewer stands in the shadows and watches as a single candle illuminates the contemplative young Mary Magdalene. She holds a skull, perhaps an example of vanitas often associated with still life works in Flanders, which are works with which de la Tour would have been familiar.

1640

Oil on canvas

Source: This work is adapted from Sophia author Ian McConnell.