Table of Contents |

Often, businesses must make decisions about investing their resources in long-term investments to add to or improve capital assets. Capital assets are significant pieces of property that have useful lives of longer than one year. Some examples of capital assets are buildings, land, machinery, vehicles, or computer equipment. Major investments in capital assets are commonly known as capital projects or capital investments. Capital projects are large-scale projects that require the use of resources for extended periods. Capital projects increase the book value of capital assets for the company. Because resources are finite, decisions to tie them up in long-term projects need to be heavily scrutinized, through a process called capital budgeting.

| Capital Project Examples |

|---|

| Construction of a new facility |

| Renovate buildings |

| Purchase land |

| Purchase of equipment |

| Sign a long-term lease |

| Purchase of computer software |

Capital projects can either be tangible or intangible. Tangible capital assets are those with a physical presence, like land, buildings, vehicles, and equipment that businesses invest in to turn a profit. Intangible assets are those assets that do not have a physical presence but also help the company make a profit, like software, patents, and licenses. The process and methods we will be discussing for evaluating capital projects are the same whether the projects concern tangible or intangible assets.

Businesses have to make decisions on whether or not to invest in long-term projects that will tie up their resources for a period of time. Capital budgeting is the process of considering alternative capital projects and selecting those alternatives that provide the most profitable return on available funds, within the framework of company goals and objectives.

This is no small task, as a business may have to choose between various capital projects, each of which may require different amounts and types of resources, offer different returns on investment, and represent different degrees of alignment with the company identity.

Through capital budgeting, management can compare the costs of a capital project against cash flows generated by the project. If the future cash flows generated by the project exceed the costs of the project, value has been created. How much value needs to be created before a project is funded is a managerial decision that is usually based on a return on investment standard. Traditionally, businesses have mechanisms by which they evaluate capital projects as well as minimum standards of return. These minimum standards of return or ROI are predetermined and work as stop-gaps, so only projects that are deemed financially beneficial are funded. We will discuss the various mechanisms of capital project evaluation later in this unit.

Capital budgeting is tied in with the concept of time value of money. Time value of money is the principle that a sum of money that you have now is more valuable than that same sum of money in the future. Time value of money works under the assumption that money can be invested, so there will be a return on that investment. The money that you have today will grow if it is invested, so that—if investments go as planned—it will be a larger sum of money later than the amount you began with. Businesses must consider the time value of money when making capital budgeting decisions, so they can make wise investment choices. Time value of money is an important managerial concept and is what decision makers use to base target rates of return upon.

However, not all investments will generate the cash flows that are anticipated. A capital investment could succeed or fail, in varying degrees as well. It is important to take into account that any future cash flows and interest earned are predicted, in order to calculate project viability. With any investment, there is a level of risk, of which management must be aware. For example, money in hand is all but guaranteed to earn a predictable cash flow in the form of interest if it's invested in a government bond or high yield savings account, but government bonds and savings accounts are not capital investments because they have low returns and do not help the company accomplish its mission. Poor capital-budgeting decisions can be costly because of the large sums of money and relatively long periods involved. If a poor capital budgeting decision is implemented, the company can lose all or part of the funds originally invested in the project and not realize the expected benefits. Poor capital-budgeting decisions may also harm the company's competitive position because the company does not have the most efficient productive assets needed to compete in world markets. For example, if a company invests in a machine that does not produce efficiently, they may not have enough inventory at the right price to satisfy customers’ needs, potentially causing the customers to buy a competitor’s product. On the other hand, failure to invest funds in a fruitful project also can be costly, both monetarily and in lost market share.

IN CONTEXT

Even large companies can fail to make sound capital budgeting decisions. Kodak dominated the photographic film market for most of the 20th century with their innovative cameras and film sales. This film market dominance led to the phrase “Kodak Moment” to symbolize a time one would want to chronicle on film. All of that came to a halt in 2012, when Kodak declared bankruptcy. What happened?

Kodak decided not to make capital investments into digital technology until most of its competitors had already done so. Kodak, seeing how its market was shrinking, then delved into digital, but it was too late. Kodak’s customers continued to flee to other digital providers. The lesson in this story is cautionary. Failure to make the right capital decisions can haunt companies, even those who are market leaders with large capital budgets.

When considering a capital project, managers need to take an objective approach. Using gut feelings or hunches may sound good in a CEO's memoir, but there are no substitutes for conducting careful research to evaluate a potential project, preparing and implementing well designed budgets, and reviewing completed projects for useful lessons. This is where the six steps in the capital budgeting process guide decision makers to make well-informed decisions. Using these steps, decision makers can make the best possible use of funds.

Companies need to be proactive and look to their markets to define areas of opportunity for capital investment.

EXAMPLE

For illustrative purposes, we will use Brian’s Bakery, a small-town bakery that is looking to expand. Brian is considering expanding the bakery in one of three ways:Once an opportunity is identified, future cash flows from a potential capital investment are determined. Risk is also examined. Risk is anything that could negatively impact your company’s finances.

EXAMPLE

Brian will need to weigh the potential cash inflows from his three options against any business risk that may occur in each.Every company will define the methodology of how it will evaluate profitability. In the following lessons, we will introduce the processes for several different common evaluation methods and the strengths and drawbacks of each.

EXAMPLE

Brian, after collecting relevant data, will determine which evaluation methodology he will use to decide which capital project to pursue. The profitability for each option must be estimated effectively, so the best possible data is used in the calculations.Companies will compare the profitability of each of the opportunities identified in step one. This is known as the capital rationing process. The Capital Rationing Process is a process of ranking opportunities that are most likely to be successful.

EXAMPLE

Once the profitability is calculated for each option, Brian will compare the outcomes of each option to decide which capital project to fund. Often, during this process, the options are ranked.At this stage, businesses fund the project or projects they choose to pursue.

EXAMPLE

Suppose that, after evaluating his three opportunities, Brian finds it most beneficial to expand production at his current facility. At this point, Brian would purchase the extra equipment (cash outflow) and measure sales (cash inflows) to determine profitability.This post audit serves as a reflective period, after the project has been implemented. Companies must evaluate if their predictive analysis of costs and benefits is true to reality.

EXAMPLE

After some time, Brian will measure his actual cash inflows against the predictions to determine the actual return on his investment. This evaluation will serve as a statement on the efficacy of his predictions of this capital project and as information for potential future investments.In the second step of the capital budgeting process, a manager must define the cash flows associated with the proposed capital investment. Cash flows can be determined and forecast through the conducting of financial research. It is also wise for businesses to account for the time value of money, since interest rates and the cost of capital can fluctuate.

The net cash inflow is the net cash benefit expected from a project in a given period. The net cash inflow is the difference between the cash inflows and the cash outflows for a proposed project.

EXAMPLE

Assume that KBB Enterprises is considering the purchase of a new excavating machine for $120,000. The equipment is expected to have:

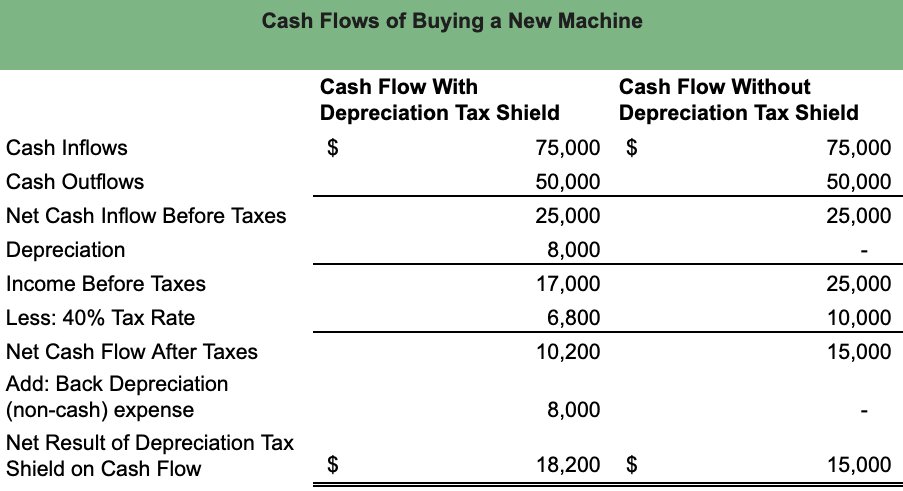

The computation of the net cash inflow usually includes the effects of depreciation and taxes. Although depreciation does not involve a cash outflow, it is deductible from federal taxable income. That is, a business can deduct the amount of capital value lost to depreciation from their taxable income, thus reducing the total income on which they owe federal taxes. This reduction is a tax saving made possible by a depreciation tax shield. A tax shield is the amount by which taxable income is reduced due to an allowable deduction—if a business's asset has $8,000 of depreciation, then the business's taxable income is reduced by a tax shield of $8,000.

EXAMPLE

Using the data from KBB Enterprises and assuming depreciation of $8,000 per year and a 40% tax rate, the amount of the tax savings is $3,200 (40% x $8,000 depreciation tax shield). Now, considering taxes and depreciation, we compute the annual net cash inflow as follows:

Sometimes a company must decide whether or not it should replace existing plant assets. Such replacement decisions often occur when faster and more efficient machinery and equipment appear on the market. The computation of the net cash inflow is more complex for a replacement decision than for an acquisition decision because there are cash inflows and outflows for two items, the asset being replaced and the new asset. These scenarios were highlighted previously in the tutorial on Equipment Decisions.

EXAMPLE

To illustrate, assume that a company operates two machines purchased four years ago at a cost of $18,000 each. The annual cash operating expenses (labor, repairs, etc.) for the two machines together total $14,000, and their depreciation totals $3,000. After the old machines have been used for four years, a new machine becomes available. The new machine can be acquired for $28,000, with annual depreciation of $3,500. The new machine has annual cash operating expenses of $10,000. The $4,000 reduction in operating expenses ($4,000 - $10,000) is a $4,000 increase in net cash inflow (savings) before taxes. The annual tax rate is 40%.

There are many other costs that are associated with capital budgeting, which provide decision makers insight on whether or not to fund a capital project. A distinction between out-of-pocket costs and sunk costs needs to be made for capital budgeting decisions. An out-of-pocket cost is a cost requiring a future outlay of resources, usually cash. Out-of-pocket costs can be avoided or changed in amount, based on management’s decisions. For example, if a manager decides not to fund a capital project, the out-of-pocket cost is avoided. Conversely, if a manager invests in a capital project, then an out-of-pocket cost is purposefully incurred. Future labor and repair costs are examples of out-of-pocket costs.

In a previous lesson on Differential Analysis, we discussed irrelevant costs, including sunk costs which are costs already incurred due to a decision made in the past. Nothing can be done about sunk costs at the present time; they cannot be avoided or changed in amount. The price paid for a machine becomes a sunk cost the minute the purchase has been made. The amount of that past outlay cannot be changed, regardless of whether the machine is scrapped or used. Thus, depreciation is a sunk cost because it represents a past cash outlay. Businesses may also invest in natural resources that are meant for extraction and intangible assets like patents. These assets are also tax shelters like depreciation but are called depletion and amortization respectively. Depletion is an accounting allocation of the extraction of natural resources such as ore deposits, and amortization is the spreading out of the costs for long-term intangible assets like patents. Depletion and amortization are also sunk costs.

| Sunk Cost | Out-of-Pocket Cost | |

|---|---|---|

| Past cost | Future cost | |

| Examples |

|

|

| Key Features |

|

Relevant to capital budgeting |

Any cash outflows necessary to acquire an asset and place it in a position and condition for its intended use are part of the original cost of the asset. Initial cost is the total price associated with the purchase of an asset, taking into consideration all of the money that is spent to purchase it and to put it to use. Initial cost is used in calculating depreciable value.

The cost of capital is important in project selection. Certainly, any acceptable proposal should offer a return that exceeds the cost of the funds used to finance it. Cost of capital, usually expressed as a rate, is the cost of all sources of capital (debt and equity) employed by a company.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM “ACCOUNTING PRINCIPLES: A BUSINESS PERSPECTIVE” BY hermanson, edwards, and maher. ACCESS FOR FREE AT www.solr.bccampus.ca. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 3.0 UNPORTED.