In this tutorial, you will learn how companies determine and plan for capacity. In specific, this tutorial will cover:

1. Capacity and Demand

As you learned in the previous tutorial, facilities layout and design are intended to maximize production and minimize costs while maintaining a safe and comfortable environment for workers. But you may also recall from previous challenges that inventory management strives to keep inventory low, even nonexistent, so there is less cost in storage and potential losses due to damage and theft.

Because of this, maximizing production does not mean “make as many as we can,” but “make as many as we can sell.” That is, you want your facilities to be able to meet demand but not to exceed it. Moreover, you want them to be scalable, to be able to increase production if demand increases.

This raises two essential questions we will answer in the next two tutorials: How do companies forecast demand, and how do they plan their facilities to be scalable, able to ramp up production as demand increases? These two topics are closely interconnected.

We will begin with capacity planning. Capacity refers to a system’s potential for producing goods or delivering services over a specified time interval. Capacity planning is doing the analysis and facilities design to reach an optimal level where production capabilities meet demand. Capacity needs include equipment, space, and employee skills. If production capabilities are not meeting demand, high costs, strains on resources, and customer loss may result. It is important to note that capacity planning has many long-term concerns given the long-term commitment of resources.

Excess capacity arises when actual production is less than what is achievable or optimal for a firm. This often means that the demand in the market for the product is below what the firm could potentially supply to the market. Excess capacity is inefficient and will cause manufacturers to incur extra costs or lose market share.

The most important concept of capacity planning is to find a balance between long-term supply and capabilities of an organization and the predicted level of long-term demand. Organizations also have to plan for actual changes in capacity, changes in consumer wants and demand, technology, and even the environment. When evaluating alternatives in capacity planning, managers must consider qualitative and quantitative aspects of the business. These aspects involve economic factors, public opinions, and personal preferences of managers.

Capacity planning involves long-term and short-term considerations. Long-term considerations relate to the overall level of capacity; short-term considerations relate to variations in capacity requirements due to seasonal, random, and irregular fluctuations in demand.

-

- Capacity

- A system’s potential for producing goods or delivering services over a specified time interval.

- Capacity Planning

- The analysis and facilities design to reach an optimal level where production capabilities meet demand.

- Excess Capacity

- When actual production is less than what is achievable or optimal for a firm.

2. Determining Capacity

Managers should recognize the broader effects capacity decisions have on the entire organization. Three common approaches to align capacity with demand are:

-

Leading capacity is when capacity is increased to meet expected demand.

-

Following capacity is when companies wait for demand increases before expanding capabilities.

-

Tracking capacity is when capacity is gradually increased over time to meet demand.

Two other important concepts describe the facilities themselves.

-

Design capacity refers to the maximum designed service capacity or output rate under ideal conditions.

-

Effective capacity is the design capacity with realistic limitations, allowing for materials shortages, employee absences, emergency maintenance, etc. If a company has historic data to draw on or can realistically project how much capacity may be lost due to predictable (even inevitable) setbacks, they can derive the effective capacity by simply subtracting them from the design capacity.

-

Suppose you are working on a project and need to predict how long it will take. You would likely have an “ideal” estimate based on absolutely optimal conditions, but also a more realistic estimate based on the need for breaks, expecting a few interruptions.

-

- Leading Capacity

- When capacity is increased to meet expected demand.

- Following Capacity

- When companies wait for demand increases before expanding capabilities.

- Tracking Capacity

- When capacity is gradually increased over time to meet demand.

- Design Capacity

- The maximum designed service capacity or output rate under ideal conditions.

- Effective Capacity

- Design capacity with realistic limitations, allowing for materials shortages, employee absences, emergency maintenance, etc.

3. Efficiency and Utilization

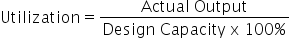

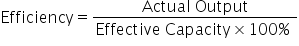

These two functions of capacity can be used to find efficiency and utilization. Utilization is how close an organization gets to reaching its operational capacity. Efficiency is how close an organization gets to reaching its goals.

These are calculated by the formulas below:

You might note that utilization will never be more than 100%—if actual output exceeds what the organization determined was its design capacity, they need to update the design capacity! Efficiency, however, can exceed 100%, if there are fewer setbacks than anticipated, or if the organization better manages them. However, since efficiency is a “best guess” of production based on factors that are hard to measure or predict, there is likely to simply be good months and bad months, and organizations should not be too hasty to decide that they should change their effective capacity until they regularly exceed it.

You may also note that utilization cannot be increased without major investments since it is already the maximum capacity under ideal conditions. Efficiency, however, can be improved with better planning. While the factors that impact efficiency are not likely to go away, the organization can be better prepared for them, such as having backup plans for supplies, and on-call staff to step in for those who are ill or absent.

Gordon’s operations team determines that they can manufacture 200 bikes a month if every person and machine is working at peak form for the entire month. But Gordon knows that they never have a month without some lost productivity, either because a machine needs to be repaired, a material needs to be restocked, or too many people are out sick to keep up peak productivity. Moreover, he knows that pushing productivity would lead to overstocking. He sets a more realistic expectation of 150 bicycles a month. For the month of May, they actually produce 160 bicycles.

- 200 is the design capacity.

- 150 is the effective capacity.

- The utilization rate is 160/200, or 80%.

- The efficiency rate is 160/150, or 107% (rounded up).

4. Improving Efficiency

As you can see, capacity planning is essentially a numbers game and a guessing game. How can companies reach the most reliable numbers and assure their “guesses” are informed estimates and not subject to either overly optimistic projects or gloom-and-doom scenarios?

When selecting a measure of capacity, it is best to choose one that doesn’t need updating. When dealing with more than one product, it is best to measure capacity in terms of each product. For example, say a firm can produce 100 microwaves or 75 refrigerators. It would be clearer for them to say this directly, specifying capacity for each product, than saying, “Our capacity is an average of 87 units.”

Another method of measuring capacity is by referring to the availability of inputs. Note that one specific measure of capacity can’t be used in all situations; it needs to be tailored to the specific situation at hand.

The determinants of effective capacity include:

- Facilities: The size and provision for expansion are key in the design of facilities. Other facility factors include locational factors (transportation costs, distance to market, labor supply, energy sources). The layout of the work area can determine how smoothly work can be performed. This is also the key measure of design capacity.

- Product and service factors: The more uniform the output, the more opportunities there are for standardization of methods and materials. This leads to greater capacity.

- Process factors: Quantity capability is an important determinant of capacity, but so is output quality. If the quality does not meet standards, then the output rate decreases because of the need to inspect and rework activities. Process improvements that increase quality and productivity can result in increased capacity. Another process factor to consider is the time it takes to change over equipment settings for different products or services.

- Human factors: The tasks that are needed in certain jobs, the array of activities involved, and the training, skill, and experience required to perform a job all affect the potential and actual output. Employee motivation, absenteeism, and labor turnover all affect the output rate as well.

- Policy factors: Management policy can affect capacity by allowing or not allowing capacity options such as overtime or second or third shifts.

- Operational factors: Scheduling problems may occur when an organization has differences in equipment capabilities among different pieces of equipment or differences in job requirements. Other areas of impact on effective capacity include inventory stocking decisions, late deliveries, purchasing requirements, acceptability of purchased materials and parts, and quality inspection and control procedures.

- Supply chain factors: What impact will the changes have on suppliers, warehousing, transportation, and distributors? If capacity is increased, will these elements of the supply chain be able to handle the increase? If capacity is to be decreased, what impact will the loss of business have on these elements of the supply chain?

- External factors: Minimum quality and performance standards can restrict management’s options for increasing and using capacity.

In business terminology, issues that can be fixed internally are known as

problems, while factors outside of organizational control (such as supply chain issues or government regulations) are

constraints under which they must work. To improve efficiency, an organization would focus on problems, particularly process factors and human factors. What elements of the process can operate more smoothly? Observation may be enough to determine any issues, such as a machine that frequently needs repairs or a single step in the process that takes longer than the others and holds up the production line. If the problems are not obvious, a more detailed analysis may be needed. Human factors can be addressed through training but also through organizational efforts to retain and motivate staff to avoid turnover and absenteeism.

Improving some factors, particularly process factors, may take trial and error—that is, the willingness to experiment with changes to the process, knowing they might not be successful. In this case, the company would probably want to take one initiative at a time, where the biggest perceived problem is, as trying to fix multiple problems at once will make it hard to analyze its success; whether efficiency increases or decreases, it will not be clear which change is responsible. However, this is more rigorous than simply making changes and seeing if they work. The process looks more like this:

- Estimate potential capacity.

- Evaluate existing production process for problems.

- Identify alternatives for solving a problem.

- Conduct financial analyses of each alternative.

- Assess key qualitative issues for each alternative.

- Select the alternative to pursue that will be best in the long term.

- Implement the selected alternative.

- Monitor results.

In terms of constraints, if these are determined to be the main reason for low efficiency, a CVP analysis may be done. Recall that CVP stands for cost-value-production; we looked at how it may be applied to selecting a site for facilities, but it is equally valuable here. If the company cannot achieve production to reach the break-even point, due to constraints outside of their control, they need to make big decisions and big changes.

-

- Problems

- Limitations within a company that can be resolved.

- Constraints

- Limitations outside of the company’s control.

In this tutorial, you learned that capacity refers to the potential of a system to deliver goods or services over a period of time, and capacity planning is the analysis and design to reach optimal levels of production where capacities meet demand. There are three approaches to determining capacity: leading, following, and tracking capacity. In determining capacity, companies also look at the facilities themselves, including the design capacity (maximum possible production) and effective capacity (practical and realistic production) of their facilities. Companies can use simple formulas to determine efficiency and utilization. Efficiency measures how well the company is achieving its effective capacity, while utilization is how well the company is using its resources. Improving efficiency involves understanding and transforming the facilities themselves, product and service factors, process factors, human factors, policy factors, operational factors, supply chain factors, and external factors. In planning improvement, it is important to distinguish between problems, those issues that can be resolved internally, and constraints, the external factors outside of the company’s control.