Table of Contents |

Modern political campaigns in the United States are expensive and growing more expensive all the time. For example, in 1986, the costs of running a successful House and Senate campaign were $849,111 and $7,243,782, respectively, in 2020 dollars. By 2020, those values had shot up to $2.4 million and $27.2 million.

Party leaders often spend some of the money they raise on other candidates within their party (Figure 1).

Raising this amount of money takes quite a bit of time and effort. A recent presentation given to incoming Democratic representatives suggested a daily Washington schedule of five hours reaching out to donors, while only three or four of engaging in actual congressional work. As this advice reveals, raising money for reelection constitutes a large proportion of the work a congressperson does.

This has caused many to wonder whether the amount of money in politics has become a corrupting influence. Many worry that “big money” exerts a disproportionate influence on the positions elected officers take.

Overall, however, the lion’s share of direct campaign contributions in congressional elections comes from individual donors, who may be less influential than the political action committees (PACs) that contribute the remainder.

IN CONTEXT

In the 2024 presidential election cycle, candidates for all parties raised a total of $1.6 billion dollars for campaigns and spent $1.3 billion. Congressional candidates raised $3.3 billion. The amount raised by political action committees (PACs), which are organizations created to raise and spend money to influence politics and contribute to candidates’ campaigns, was approximately $12.3 billion.

Concerns that money buys influence with politicians have given rise to laws that limit or regulate campaign contributions, although some of the most impactful measures have since been invalidated by the Supreme Court.

For nearly the first hundred years of the republic, there were no federal campaign finance laws. This changed at the end of the nineteenth century. In the 1896 election, the Republican Party spent a whopping $16 million! In response, in 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt pushed Congress to pass the Tillman Act (1907), which prohibited corporations from contributing money to candidates running in federal elections.

Other congressional acts followed, limiting how much money individuals could contribute to candidates, how candidates could spend contributions, and what information would be disclosed to the public. However, these laws were full of loopholes and were easily skirted by those who knew how to navigate the system.

In 1971, Congress again tried to address campaign financing by passing the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA).

Some argued that the FECA violated the First Amendment’s protection of free speech. In fact, in Buckley v. Valeo (1976), the Supreme Court considered this very question. The Court ruled that limits on independent expenditures, or money spent on communication in support of or against a candidate, as well as limits on expenditures by candidates from their own personal or family resources, violated the First Amendment. However, the Court ruled that limits on campaign contributions, including how much individuals could contribute to a candidate or a campaign, were allowable and important to the integrity of the democratic system.

In 1976, the FEC began enforcing campaign finance laws and continues to enforce them today.

Even with the new laws and the FEC, there were loopholes. Labor unions, corporations, and individuals could contribute large sums known as “soft money” to political parties and political action committees, who in turn could use it for party-building efforts, get-out-the-vote efforts, and issue-advocacy ads. Unlike “hard money” which contributed directly to a candidate, which is heavily regulated and limited, soft money had almost no regulations or limits. It had never been a problem before the mid-1990s when a number of imaginative political operatives developed a great many ways to spend this money. After that, soft-money donations skyrocketed.

As a result, Congress passed the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA), also referred to as the McCain–Feingold Act (Figure 2).

The FEC’s enforcement of the law spurred numerous court cases challenging it. The most controversial decision was handed down by the Supreme Court in 2010, in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.

Even more importantly, the Citizens United decision also led to the removal of spending limits for corporations. As critics of the decision predicted at the time, the Court has opened the floodgates for private money to flow into campaigns again.

The Court’s decision allowed for the emergence of a new type of advocacy group, the super PAC.

As discussed, a traditional political action committee is an organization designed to raise money to elect or defeat candidates.

EXAMPLE

Businesses, labor unions, such as the Teamsters Union, and issue-based interest groups, such as the National Rifle Association, tend to form PACs.PACs are highly regulated in regard to the amount of money they can take in and spend.

Super PACs aren’t bound by these regulations. The court ruling allowed corporations to place unlimited money into super PACs. These organizations cannot contribute directly to a candidate, nor can they strategize with a candidate’s campaign. They can, however, raise and spend as much money as they please to support or attack a candidate, including running advertisements and hosting events.

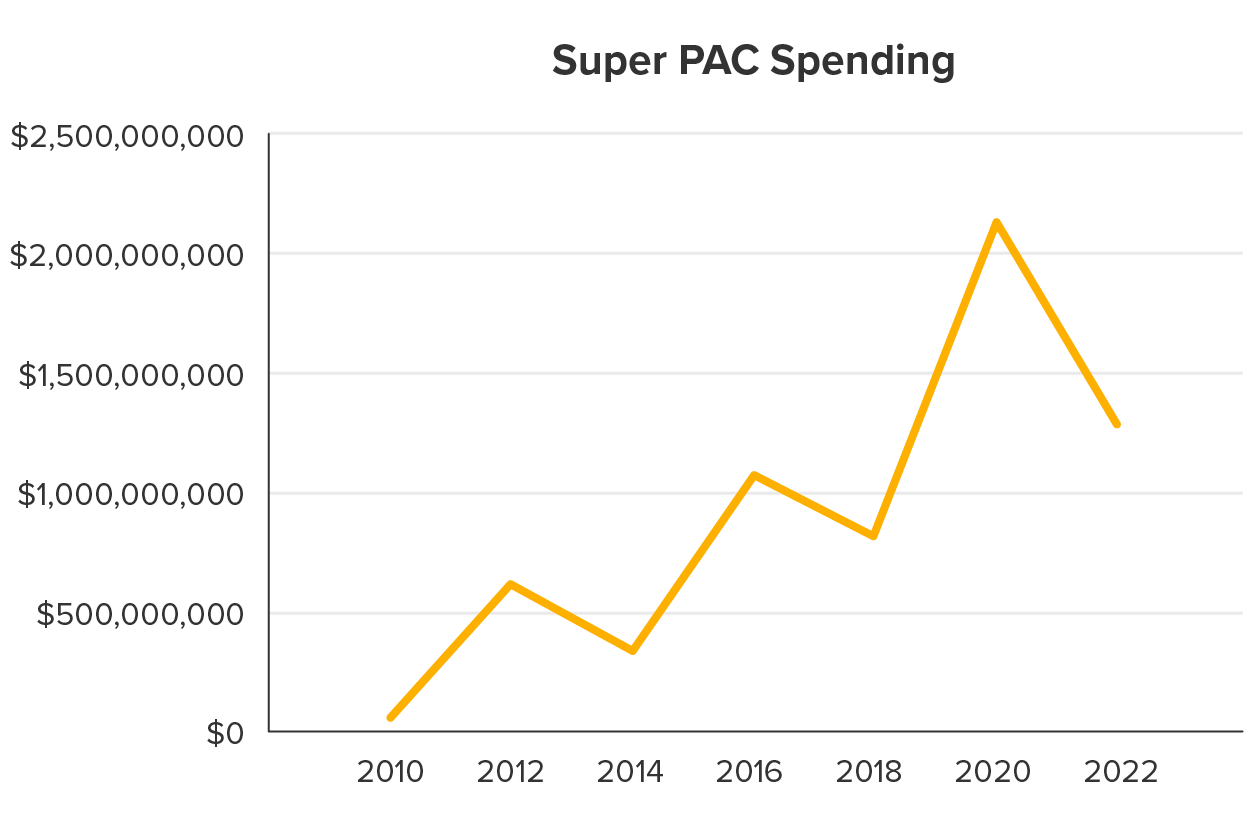

The amount of money super PACS have been spending has increased rapidly (Figure 3).

Figure 3 shows how campaign spending always rises in presidential election years, such as 2012, 2016, and 2020, and falls in the midterm election years, such as 2014 and 2018. However, the overall trend is a steep rise.

Unlike interest groups and PACs that tend to support candidates on both sides of the political aisle, super PACs tend to support either conservative or liberal candidates. They are often identified with party leaders or presidential candidates.

EXAMPLE

In 2020, the Senate Leadership Fund, a conservative super PAC, spent $293.7 million supporting conservative candidates, while the Senate Majority PAC spent $230.4 million supporting liberal candidates.Despite the Citizens United decision, several limits on campaign contributions have been upheld by the courts and remain in place as of 2025.

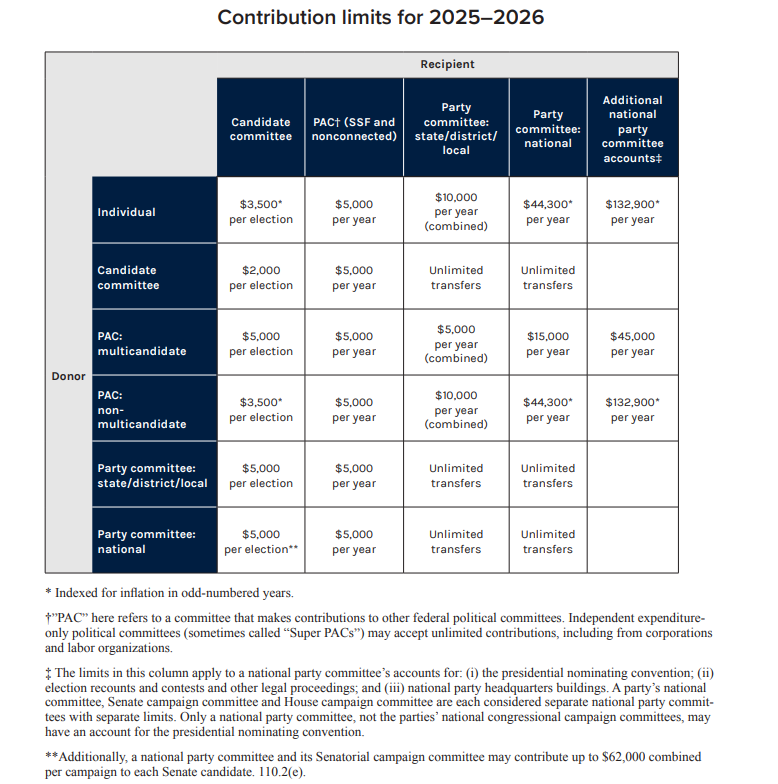

Individuals may contribute up to $3,500 per candidate per election. This means a teacher living in Nebraska may contribute $3,500 to a candidate for their campaign to become the Democratic presidential nominee, and if that candidate becomes the nominee, the teacher may contribute another $3,500 to their general election campaign.

Individuals may also give up to $5,000 to political action committees and $44,300 to a national party committee.

PACs that contribute to more than one candidate are permitted to contribute $5,000 per candidate per election and up to $15,000 to a national party. PACs created to give money to only one candidate are limited to only $3,500 per candidate, however (Figure 4). The amounts are adjusted every two years, based on inflation. These limits are intended to create a more equal playing field for the candidates so that candidates must raise their campaign funds from a broad pool of contributors.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “AMERICAN GOVERNMENT 3E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/DETAILS/BOOKS/AMERICAN-GOVERNMENT-3E. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

References

Oyez. (n.d.). Buckley v. Valeo. www.oyez.org/cases/1975/75-436