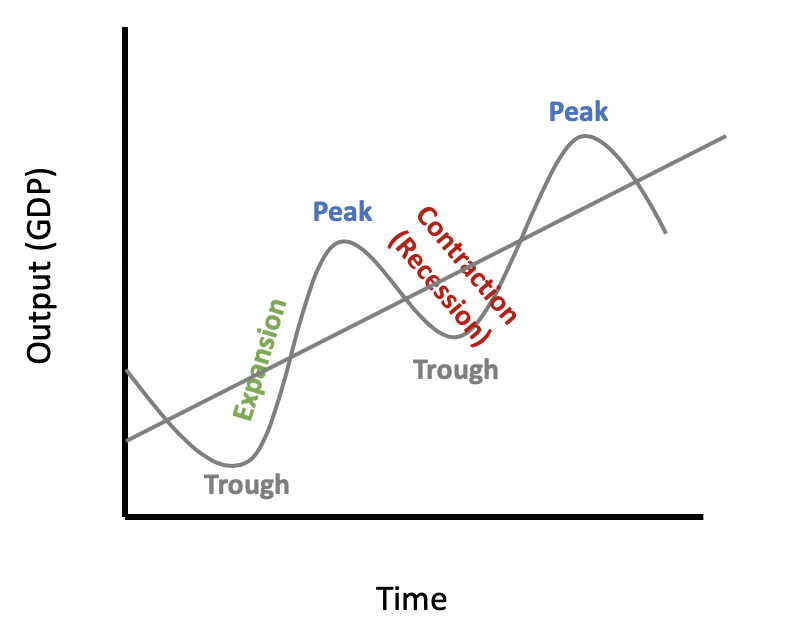

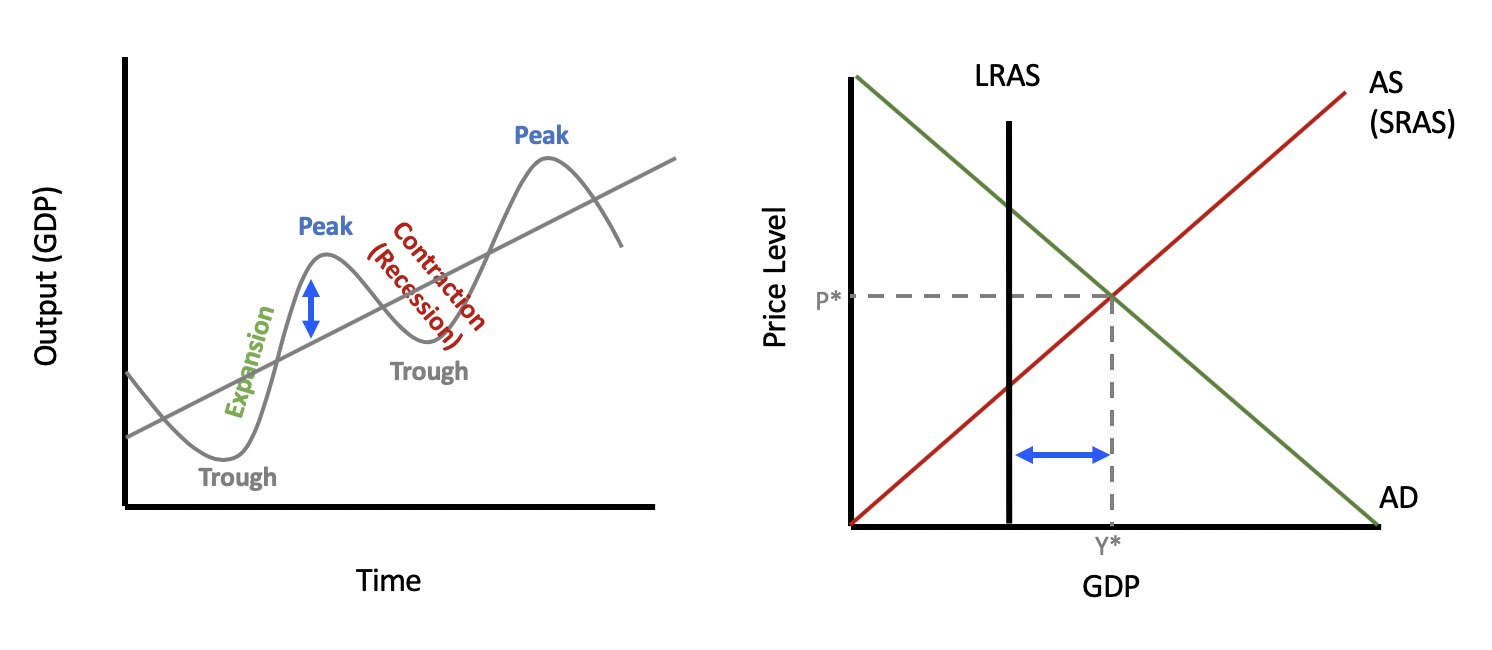

In review, this is a business cycle. We know that it is normal for the economy to go through periods of growth and contraction.

Over time, GDP tends to grow, represented by the gray line, which shows the overall growth trend.

Now, there are times the GDP grows quickly, and times that it can shrink.

We can see these periods of growth and contraction in more detail using our aggregate demand and aggregate supply model, so let's review the components of this model.

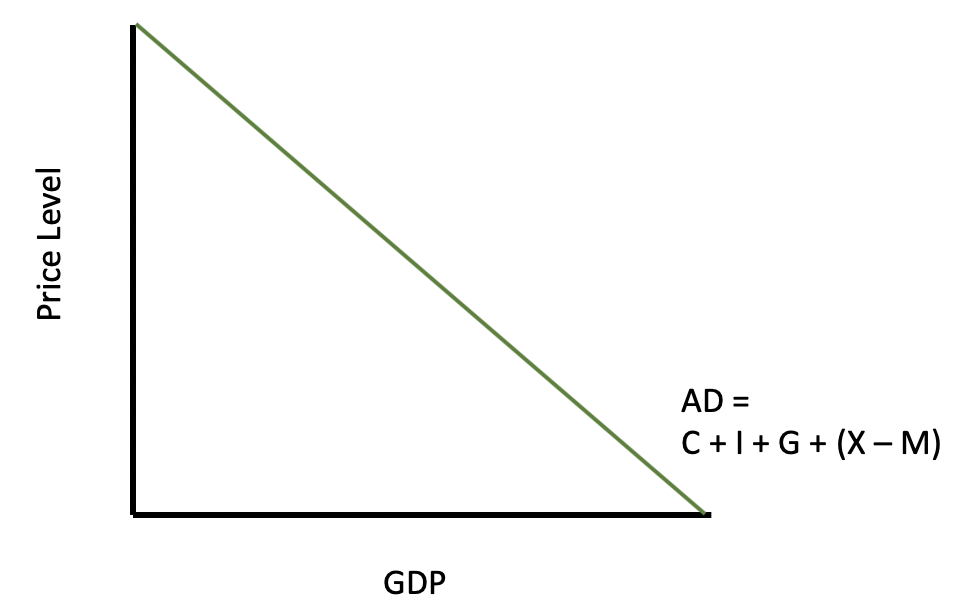

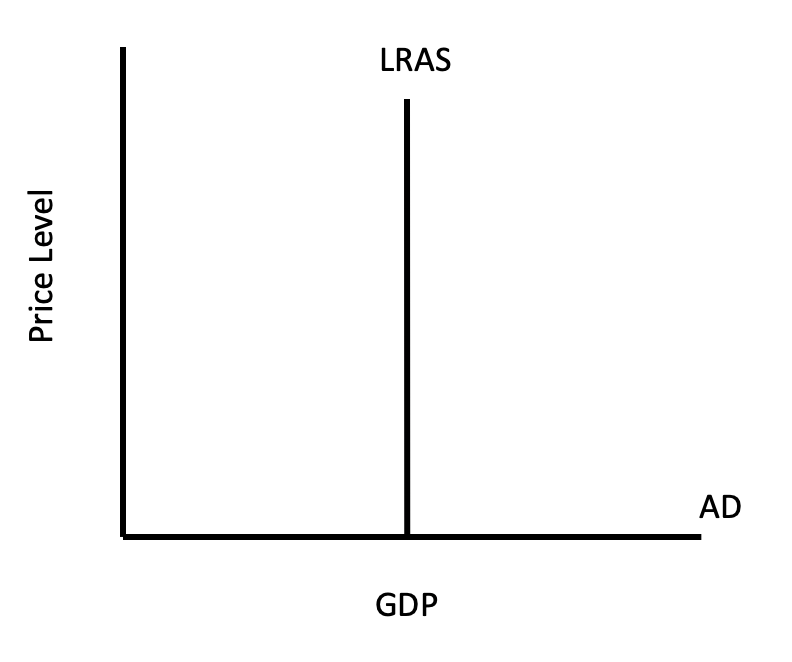

Aggregate demand, as you will recall, is the total amount of goods and services demanded in the economy at a specific point in time and at a prevailing price level.

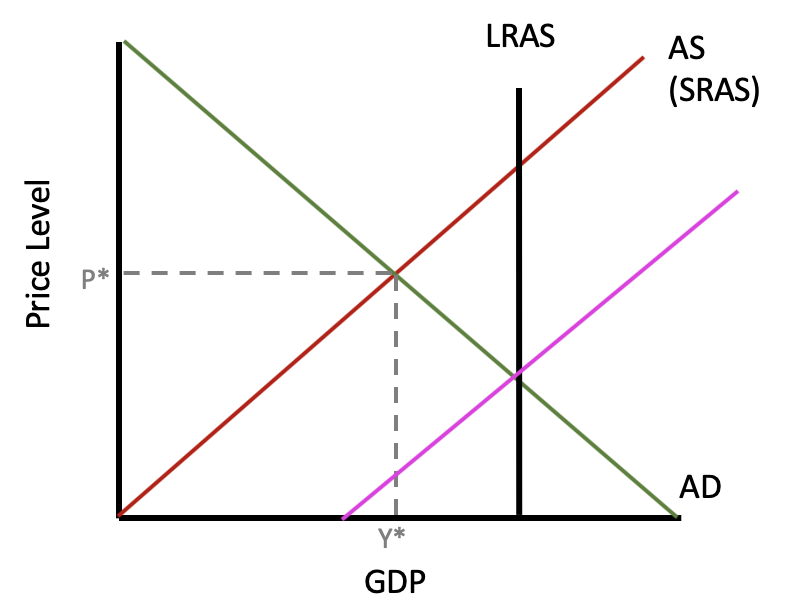

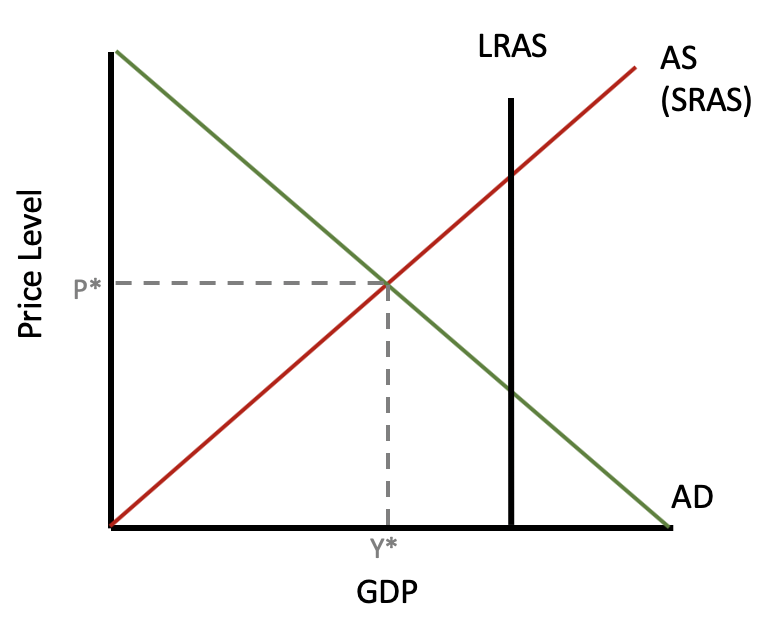

Here is our aggregate demand curve. It is a downward sloping curve, showing an inverse relationship between the price level and real GDP. This means that people--the consumers, firms, governments, and net foreign purchases of U.S. goods--will want to purchase more as the overall price level falls.

This is due to the three effects:

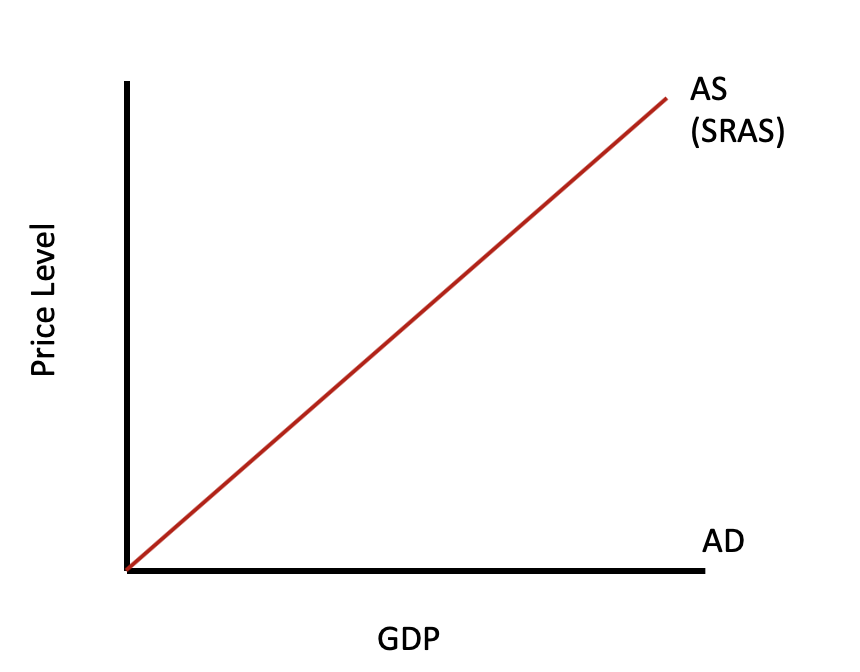

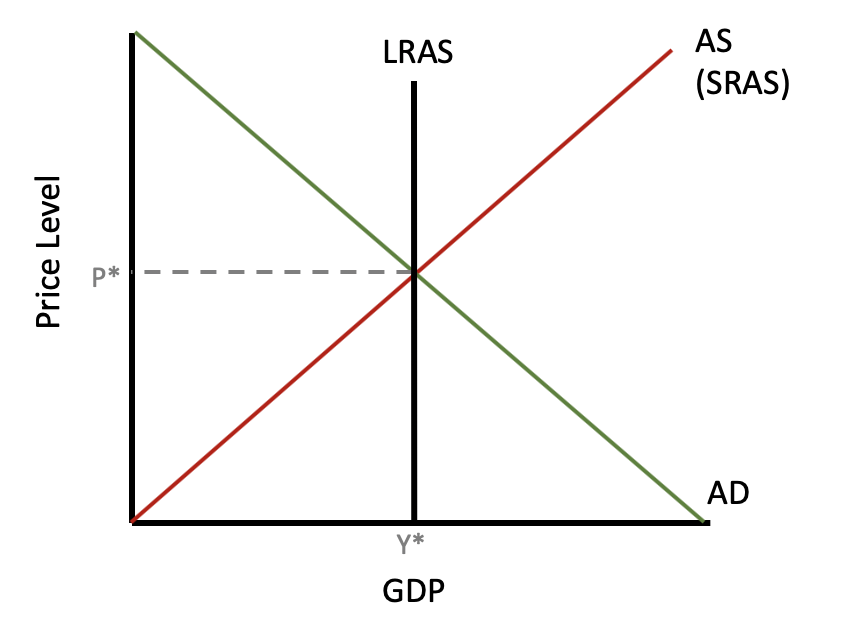

Short run aggregate supply, or SRAS, is assumed to maintain a positive price and quantity correlation, showing that more can be produced in the short run through increased resource utilization, technological improvements, or other factors.

Here is a short run aggregate supply curve. It is an upward sloping curve because, in the short run, businesses can actually produce more as prices go up because they won't have to pay their workers more immediately. They can also use inventories that they already have.

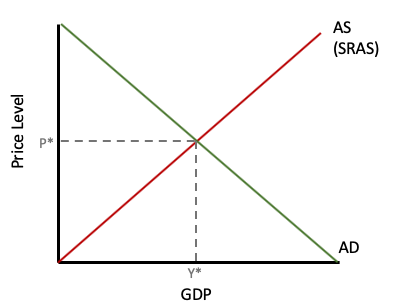

If we put these the aggregate demand and aggregate supply curves together, we can see that the intersection gives us equilibrium, where Y* is the real GDP, or current level of production, and P* is the current price level.

Now we have to add in the long run aggregate supply or LRAS. Recall that long-run aggregate supply is assumed to be constant in the long run, because in the long run, resources are assumed to be used optimally.

If we are at the long run aggregate supply curve, you can see that there is no potential for increasing capacity, so it is represented by a vertical line, as shown below. This shows our economy's full potential in terms of production given our current resources.

Ramping up production in the short run can only get us so far, because, in the long run, we have a limited amount of resources, like materials, workers, etc.

So, if we put these three things together, this graph shows the economy currently producing where long-run aggregate supply intersects short-run aggregate supply and aggregate demand.

This means that currently the economy is fully employed and producing the maximum amount possible, given our current resources.

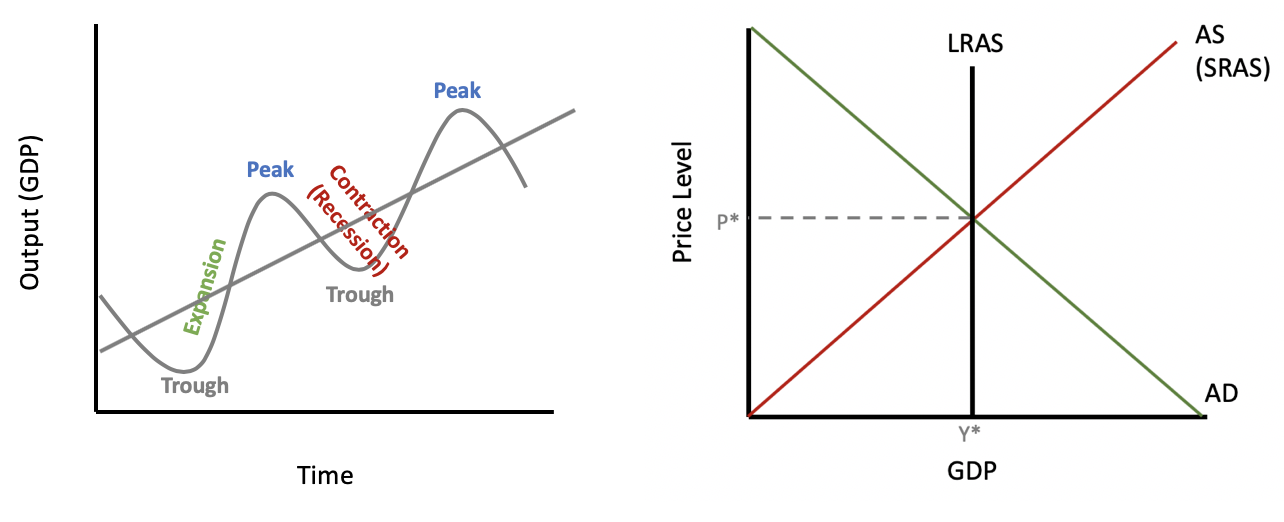

So, if we want to compare this to the business cycle, we place that growth trend on there. The long-run aggregate supply curve is a similar concept to the overall growth trend on our business cycle.

When the economy is producing in equilibrium, we are right on our growth trend in the business cycle, producing exactly a sustainable quantity with our resources.

Note, the business cycle model doesn't show price level, whereas the AD/AS model does, because it provides a snapshot of a point in time. The idea, though, is that we are on the growth trend in the business cycle if we are producing at our long-run aggregate supply curve.

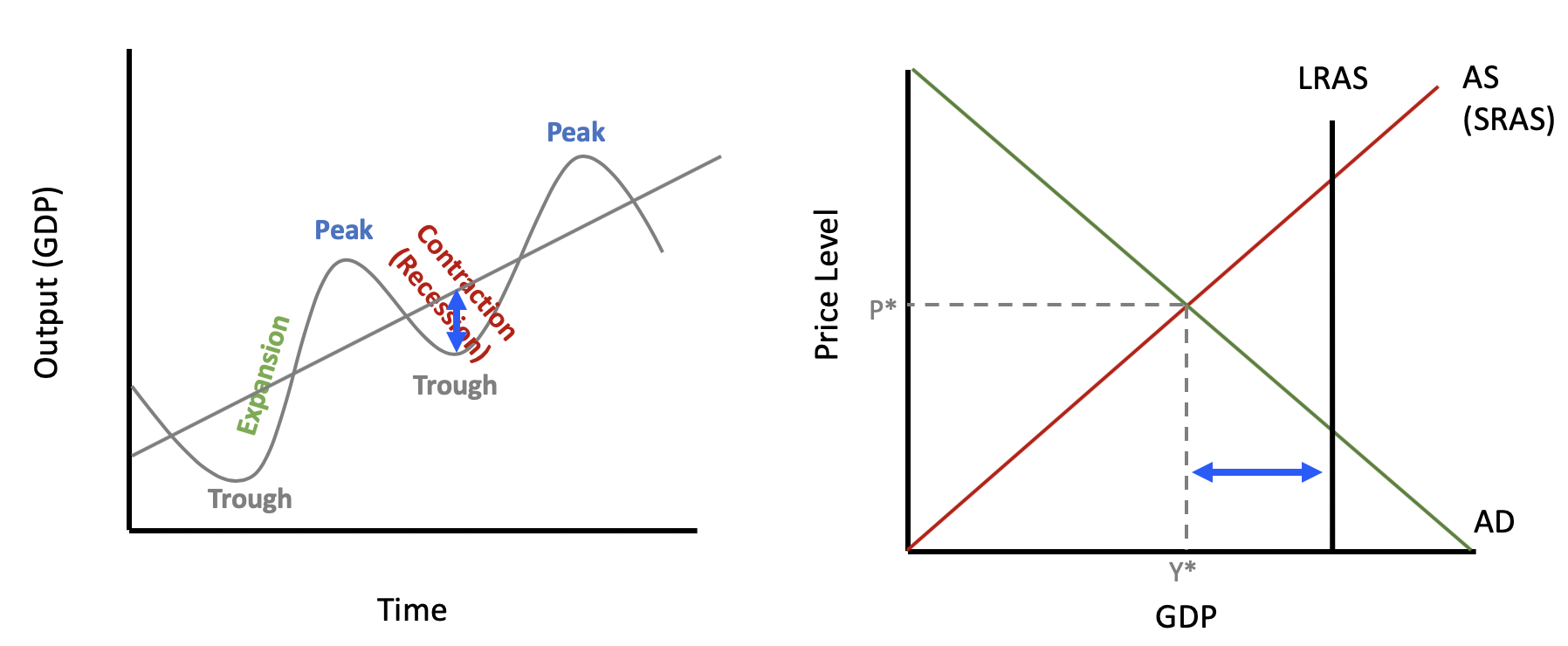

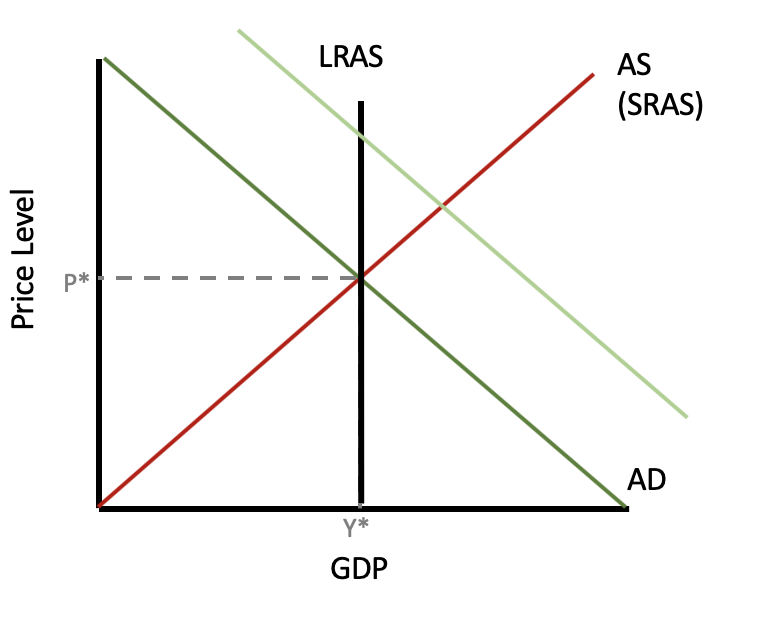

Now, the economy during a recession is different. This graph shows the economy currently producing at a real GDP less than the long-run aggregate supply.

This means that the unemployment rate has risen; we are not fully employed. We are producing less than our full potential. This recessionary gap can be seen on the business cycle at a point below the growth trend, possibly near a trough.

Notice the blue arrows. We can compare the distance horizontally on the AD/AS graph, which shows how much unemployment has increased, with the vertical distance on the business cycle.

A trough, remember, is the business cycle period that coincides with the lowest GDP for a given point in time.

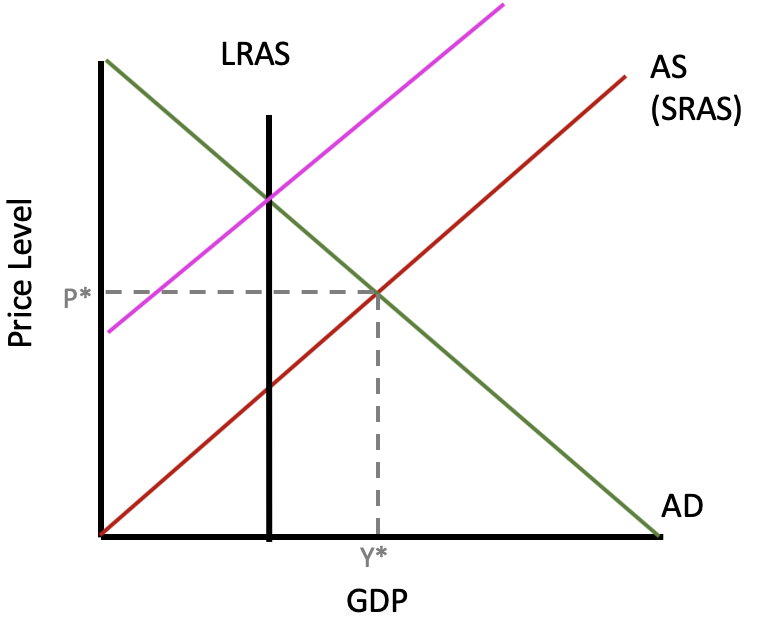

Now let's look at an expansion. In an expansionary period, our economy is currently producing at a real GDP greater than the long-run aggregate supply. On the business cycle, we are producing above our growth trend.

Once again, you can see by the blue arrows that the horizontal difference on the AD/AS model is the same as the vertical difference on the business cycle.

This is possible because, if you recall, a peak is the business cycle period that coincides with the maximum obtainable GDP for a given point in time.

So, when we're at an unsustainable price or output combination at a peak, it looks like the AD/AS model above. It is possible, in the very short run, because we can move beyond that, but let's look at what is going to happen.

Because demand has risen, prices are going to rise. Consumers are willing to pay more.

Producers now want to produce more, and they can, by drawing down their inventories and using resources faster than they are being replaced.

However, this is not sustainable, which is why the long run aggregate supply curve is located where it is. Once inventories are depleted and producers need to order more, there will be shortages at those previous prices, and the prices of inputs will start to rise.

This is going to shift our short-run aggregate supply curve to the left. As input prices go up, SRAS shifts to the left and brings us right back to our long-run aggregate supply.

IN CONTEXT

There was a housing boom that occurred in the early 2000s, during which there was a huge increase in demand, represented here with that new aggregate demand curve.

Because prices are rising, as you can see on the curve, builders responded by trying to build more and more--and they did.

At some point, though, their costs--like lumber, for instance--began to rise, because there was only so much that can be produced in a given time frame.

It is actually possible for the market to self-correct. With increased costs of production, as mentioned, the short-run aggregate supply curve can shift to the left, because builders have to charge higher prices for homes.

We move right back to our sustainable long-run aggregate supply level of real GDP. The market has essentially corrected itself through changes in the price level.

However, keep in mind that although we are back at the sustainable level of real GDP, notice that prices have significantly risen from where they were.

Now, will this same self-correction occur when the economy is in a recession?

Here is an AD/AS model during a trough, or in a recession. In theory, since inventories are starting to build up due to low demand, suppliers might start to lower prices.

If they did, that would allow SRAS to shift to the right. Workers might even be willing to work for less as unemployment is high during a recession.

If prices do fall, then the market can naturally correct, bringing the economy back to full employment.

However, this isn't as common as we saw with the opposite, in an expansionary economy.

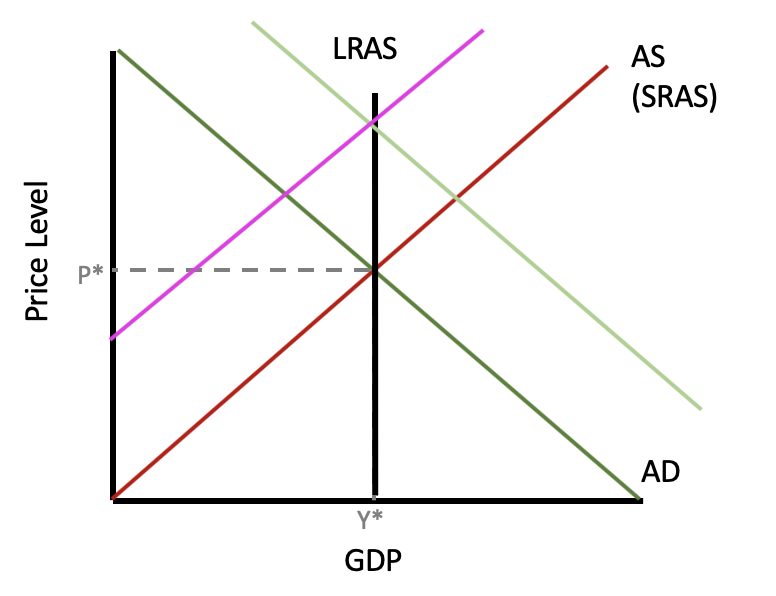

So, if it doesn't occur, if prices do not adjust downward, then we could be stuck here:

Prices do not always adjust downward. When suppliers are reluctant to lower prices, as they commonly are, prices are said to be sticky.

In this case, the economy could be stuck in a recession indefinitely. For this reason, often the government and/or Federal Reserve System will intervene to try to increase aggregate demand to get us back to full employment.

More often than not, that doesn't happen because prices can be sticky. Again, sticky prices refer to prices that do not easily move below the threshold value, even though theory would anticipate a decline to reestablish our market equilibrium.

Source: Adapted from Sophia instructor Kate Eskra.