Table of Contents |

Human blood cells have multiple possible antigens on their surface. To date, 33 immunologically important blood-type systems have been identified. The exact antigens vary by ethnic group. In many cases, these systems rarely result in antibody production and do not play a major role in evaluating blood for transfusions. However, some are extremely important to assess before carrying out blood transfusions to prevent a strong immune response. The most important, which may be familiar to you (especially if you have donated blood), are the ABO and Rh blood groups that you learned about in an earlier lesson.

In this lesson, you will learn about the steps involved in assessing blood for transfusion.

Before blood can be safely used for transfusion, blood testing must be performed. This is accomplished by mixing red blood cells from each unit of blood with commercially prepared antibodies against the A, B, and Rh antigens (remember that type O blood lacks A and B antigens and that there is no O antigen). This identifies the ABO and Rh group of the blood, and blood types are named based on the presence or absence of antigens. The blood type is called positive if the Rh factor is present (e.g., type A positive) and negative if the Rh factor is absent (e.g., type A negative).

Prior to a transfusion, the patient’s blood type must be confirmed in a similar manner by mixing cells with commercially available antibodies.

Immediately prior to releasing the blood for transfusion, a crossmatch is performed to confirm that the blood types match. In this test, a small quantity of donor red blood cells are mixed with serum from the patient who needs the transfusion. If there is a good match, then no agglutination should occur. If the patient’s blood contains antibodies to antigens in the donor cells, then agglutination will occur. Coombs reagent is sometimes added to confirm any negative test results and check for sensitized red blood cells because it makes agglutination more visible.

In most cases, additional testing is not needed because transfusions generally use packed red blood cells with most of the plasma removed. However, a minor crossmatch may be used if there is concern that agglutinizing antibodies may be present in the donor serum. For this test, a small amount of donor serum is mixed with donor red blood cells to look for agglutination. If agglutination occurs, then the blood is not a good match for donation.

In some cases, it is valuable to test for other antibodies. This is generally done when women have had multiple pregnancies (exposing them to fetal antigens) or multiple transfusions. An antibody screen can be performed in which patient serum is checked against prepared, pooled, type O red blood cells that express the antigens of interest. If agglutination occurs, then the antigen causing the response must be identified. Any donor units of blood must be tested for this antigen.

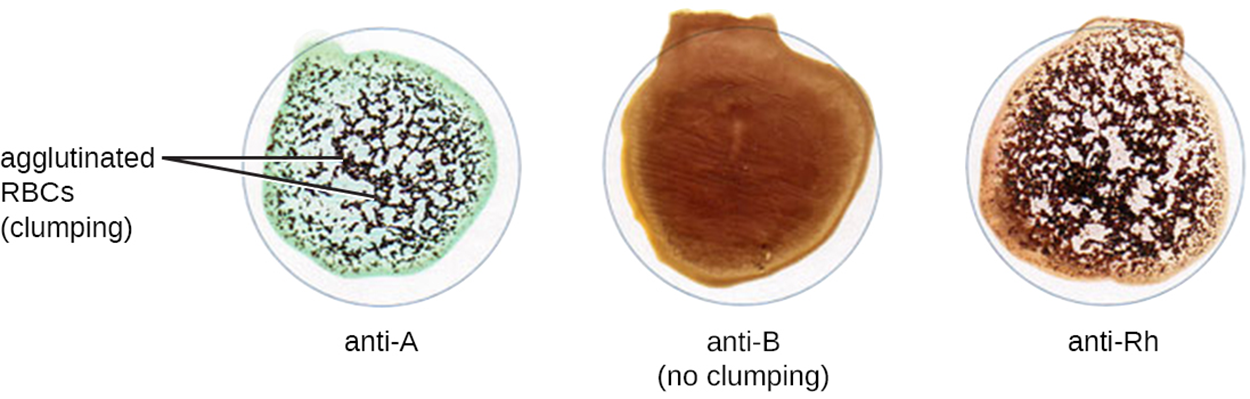

The photo below shows an example of crossmatching on a card with three wells. The left-hand well is coated with anti-A antibody, the middle well is coated with anti-B antibody, and the right-hand well is coated with anti-Rh antibody. A blood sample from the donor or recipient can be added to each well to detect agglutination. In the photo below, agglutination has occurred in the anti-A well, and therefore the blood tested contains A antigens. Because no clumping occurred in the anti-B cell, the blood does not have B antigens. There is clumping in the anti-Rh well, so the blood is Rh positive. This test indicates that the tested blood is type A and Rh positive.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “MICROBIOLOGY.” ACCESS FOR FREE AT openstax.org/details/books/microbiology. LICENSE: CC ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.