Table of Contents |

Antigens are substances that may trigger an immune response from leukocytes. Take note that antigens MAY or MAY NOT trigger an immune response. Therefore, antigens are categorized into two groups—self and foreign antigens. Self-antigens are antigens that the body has been programmed not to react to—they are part of the “self” or body. Foreign antigens are antigens that the body has not been previously programmed on and therefore are reacted against—they are foreign and should be removed.

Antigens are generally large proteins but may include other classes of organic molecules, including carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic acids. When foreign antigens enter and are identified by the body, the ultimate response is the production of antibodies, also known as immunoglobulins, one of the globulin proteins in the blood. These Y-shaped proteins are produced by a specific version of B lymphocyte called a plasma cell. Each antibody binds to a specific antigen and neutralizes it and/or facilitates its removal from the body. You will learn more about antigens and antibodies when you cover the lymphatic system. This lesson will focus on their relevance to blood typing.

The antigens that are relevant to blood typing are located on the plasma membrane surface of erythrocytes. When a patient is infused with an incompatible type of blood, the antigens on the infused erythrocytes are identified as foreign and that patient produces antibodies against them. Because the antibodies are Y-shaped, they bind to two separate antigens which inherently causes clumping among antibody-antigen complexes, a process known as agglutination.

The reason that this process carries a risk of death is that the clumps of erythrocytes and antibodies can block small blood vessels which can deprive tissues of necessary nutrients or waste removal. Additionally, as the clumps are degraded, the hemoglobin (the primary molecule found within erythrocytes) is released into circulation. This hemoglobin travels to the kidneys, which are responsible for filtration of the blood. However, the load of hemoglobin released can easily overwhelm the kidney’s capacity to clear it, and the patient can quickly develop kidney failure and death.

The ABO blood group designates four separate blood types (A, B, AB, and O) but is only based on the presence or absence of two antigens (A and B). Both are glycoproteins and their presence or absence, and therefore your ABO blood type, is genetically determined.

| Red Blood Cell Type | A | B | AB | O |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies in Plasma | Anti-B | Anti-A | None | Anti-A and Anti-B |

| Antigens in Red Blood Cell | A antigen | B antigen | A and B antigens | None |

| Can receive blood from… | A, O | B, O | A, B, AB, O | O |

| Can give blood to… | A, AB | B, AB | AB | A, B, AB, O |

The Rh blood group is classified according to the presence or absence of another erythrocyte antigen identified as Rh, DEF, or D. The label “Rh” comes from the discovery of this antigen in a primate known as a rhesus macaque, which is often used in research because its blood is similar to humans. Since then, dozens of Rh antigens have been identified. Of those, three—D, E, and F—are the most prominent. And of those three, D is the most prominent. Therefore, while this blood group can be labeled as being based on the antigen Rh, DEF, or D, all three are reporting the same information.

The following table summarizes the distribution of the ABO and Rh blood types within the United States. As you can tell, the predominant blood types are different within different subpopulations, indicating a different genetic background among each group. These numbers also differ when compared to different countries.

| Blood Type | Asian | Black non-Hispanic | Hispanic | North American Indian | White non-Hispanic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A⁺ | 27.3 | 24.0 | 28.7 | 31.3 | 33.0 |

| A⁻ | 0.5 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 6.8 |

| B⁺ | 25.0 | 18.4 | 9.2 | 7.0 | 9.1 |

| B⁻ | 0.4 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.8 |

| AB⁺ | 7.0 | 4.0 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 3.4 |

| AB⁻ | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| O⁺ | 39.0 | 46.6 | 52.6 | 50.0 | 37.2 |

| O⁻ | 0.7 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 4.7 | 8.0 |

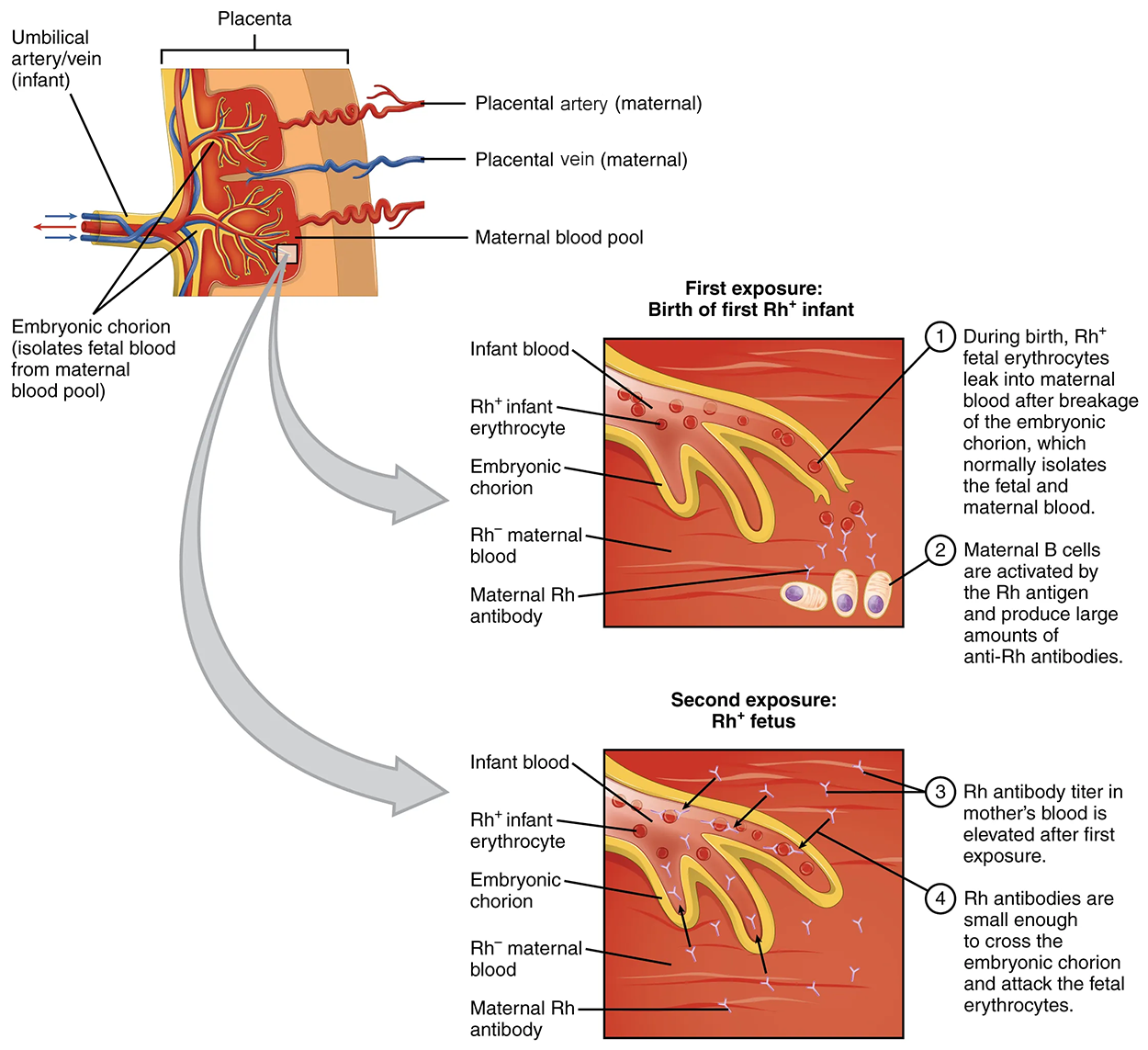

In contrast to the ABO group antibodies, which are formed prior to any potential exposure to incompatible blood, antibodies to the Rh antigen are produced only in Rh⁻ individuals after exposure to the antigen. This process, called sensitization, occurs following a transfusion with Rh⁻ incompatible blood or, more commonly, with the birth of an Rh⁺ baby to the Rh⁻ birthing parent.

During pregnancy, the fetus’s blood cells rarely cross the placenta (the organ of gas and nutrient exchange between the fetus and the birthing parent). However, the birthing parent's antibodies do cross the placenta. For the three antigens related to blood type, the anti-A and anti-B antibodies are significantly less reactive than Rh. Therefore, preexisting anti-A and anti-B antibodies are not a concern if the fetus’s blood is a mismatch for the birthing parent. However, an Rh mismatch is strongly reactive and can be a concern. Specifically, the Rh⁻ birthing parent who can produce anti-Rh antibodies against an Rh⁺ fetus is of concern.

During the first pregnancy, the Rh⁻ birthing parent has had no exposure to the Rh antigen and has not begun production of the anti-Rh antibody. Unless there is a blood vessel broken during the pregnancy, the first Rh⁺ baby is born without an issue. However, during or immediately after birth, the Rh⁻ birthing parent can be exposed to the baby’s Rh⁺ cells. Research has shown that this occurs in about 13−14% of such pregnancies. After exposure, the birthing parent’s immune system begins to generate anti-Rh antibodies. If the same person should then become pregnant with another Rh⁺ fetus, the Rh antibodies they have produced can cross the placenta into the fetal bloodstream and destroy the fetal RBCs. This condition, known as hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN) or erythroblastosis fetalis, may cause anemia in mild cases, but the agglutination and hemolysis can be so severe that without treatment the fetus may die in the womb or shortly after birth.

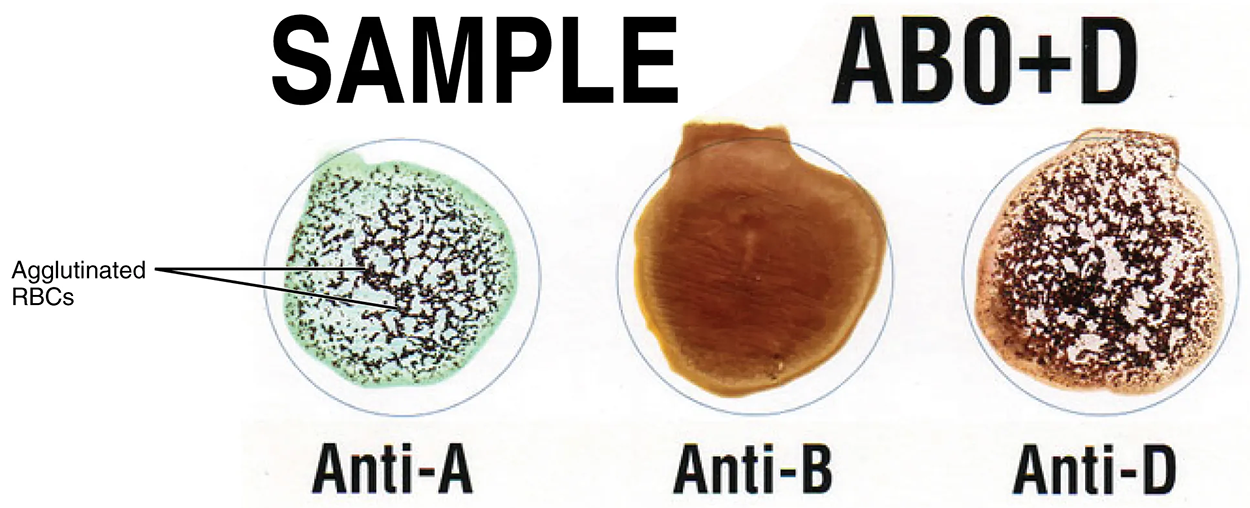

Clinicians are able to determine a patient’s blood type quickly and easily using commercially prepared antibodies. An unknown blood sample is allocated into separate wells. Into one well a small amount of anti-A antibody is added, and to another a small amount of anti-B antibody. If the antigen is present, the antibodies will cause visible agglutination (clumping) of the cells. The blood should also be tested for Rh antibodies.

| Blood Type | Anti-A | Anti-B | Anti-D |

|---|---|---|---|

| A⁺ | Clumping | No Clumping | Clumping |

| A⁻ | Clumping | No Clumping | No Clumping |

| B⁺ | No Clumping | Clumping | Clumping |

| B⁻ | No Clumping | Clumping | No Clumping |

| AB⁺ | Clumping | Clumping | Clumping |

| AB⁻ | Clumping | Clumping | No Clumping |

| O⁺ | No Clumping | No Clumping | Clumping |

| O⁻ | No Clumping | No Clumping | No Clumping |

To avoid transfusion reactions, it is best to transfuse only matching blood types; that is, a type B⁺ recipient should ideally receive blood only from a type B⁺ donor, and so on. That said, in emergency situations, when acute hemorrhage threatens the patient’s life, there may not be time for cross-matching to identify blood type. In these cases, blood from a universal donor—an individual with type O⁻ blood—may be transfused. Recall that type O erythrocytes do not display A or B antigens. Thus, anti-A or anti-B antibodies that might be circulating in the patient’s blood plasma will not encounter any erythrocyte surface antigens on the donated blood and therefore will not be provoked into a response.

One problem with this designation of the universal donor is an O⁻ individual produces anti-A and anti-B antibodies and depending on their prior exposure, may also produce anti-Rh antibodies. This may cause problems for the recipient, but because the volume of blood transfused is much lower than the volume of the patient’s own blood, the adverse effects of the relatively few infused plasma antibodies are typically limited. Although it is always preferable to cross-match a patient’s blood before transfusing, in a true life-threatening emergency situation, this is not always possible, and these procedures may be implemented.

A patient with blood type AB⁺ is known as the universal recipient. This patient can theoretically receive any type of blood because the patient’s own blood—having both A, B, and Rh antigens on the erythrocyte surface—does not produce anti-A, anti-B, or anti-Rh antibodies. However, keep in mind that the donor’s blood will contain circulating antibodies, again with possible negative implications. The table below summarizes the blood types and compatibilities.

| Blood Type | Antigens | Antibodies | Can Receive From… | Can Give To… |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A⁺ | A, Rh | B | A⁺, A⁻, O⁺, O⁻ | A⁺, AB⁺ |

| A⁻ | A | B, Rh | A⁻, O⁻ | A⁺, A⁻, AB⁺, AB⁻ |

| B⁺ | B, Rh | A | B⁺, B⁻, O⁺, O⁻ | B⁺, AB⁺ |

| B⁻ | B | A, Rh | B⁻, O⁻ | B⁺, B⁻, AB⁺, AB⁻ |

| AB⁺ | A, B, Rh | - | A⁺, A⁻, B⁺, B-, AB⁺, AB⁻, O⁺, O⁻ | AB⁺ |

| AB⁻ | A, B | Rh | A⁻, B⁻, AB⁻, O⁻ | AB⁺, AB⁻ |

| O⁺ | Rh | A, B | O⁺, O⁻ | A⁺, B⁺, AB⁺, O⁺ |

| O⁻ | - | A, B, Rh | O⁻ | A⁺, A⁻, B⁺, B⁻, AB⁺, AB⁻, O⁺, O⁻ |

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX "ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E" ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/DETAILS/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL

REFERENCES

Yoham AL, Casadesus D. Rho(D) Immune Globulin. [Updated 2022 May 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557884/