Table of Contents |

Blood flow refers to the movement of blood through a vessel, tissue, or organ, and is usually expressed in terms of volume of blood per unit of time. It is initiated by the contraction of the ventricles of the heart. Ventricular contraction ejects blood into the major arteries, resulting in flow from regions of higher pressure to regions of lower pressure, as blood encounters smaller arteries and arterioles, then capillaries, then the venules and veins of the venous system. This lesson discusses a number of critical variables that contribute to blood flow throughout the body. It also discusses the factors that impede or slow blood flow, a phenomenon known as resistance.

Blood pressure is the force exerted by blood upon the walls of the blood vessels or the chambers of the heart. Blood pressure may be measured in capillaries and veins, as well as the vessels of the pulmonary circulation; however, the term blood pressure without any specific descriptors typically refers to systemic arterial blood pressure—that is, the pressure of blood flowing in the arteries of the systemic circulation. In clinical practice, this pressure is measured in mm Hg and is usually obtained using the brachial artery of the arm.

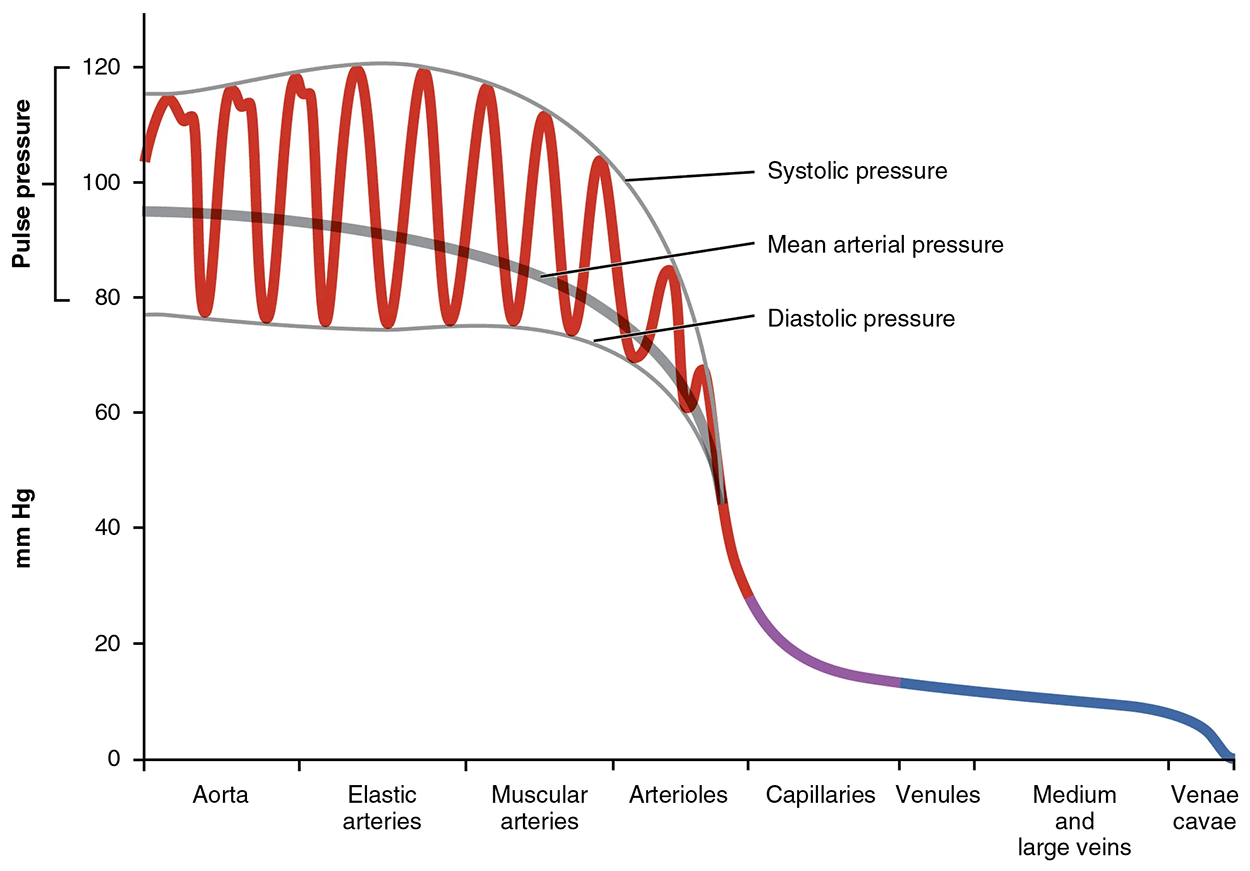

Arterial blood pressure in the larger vessels consists of several distinct components: systolic and diastolic pressures, pulse pressure, and mean arterial pressure.

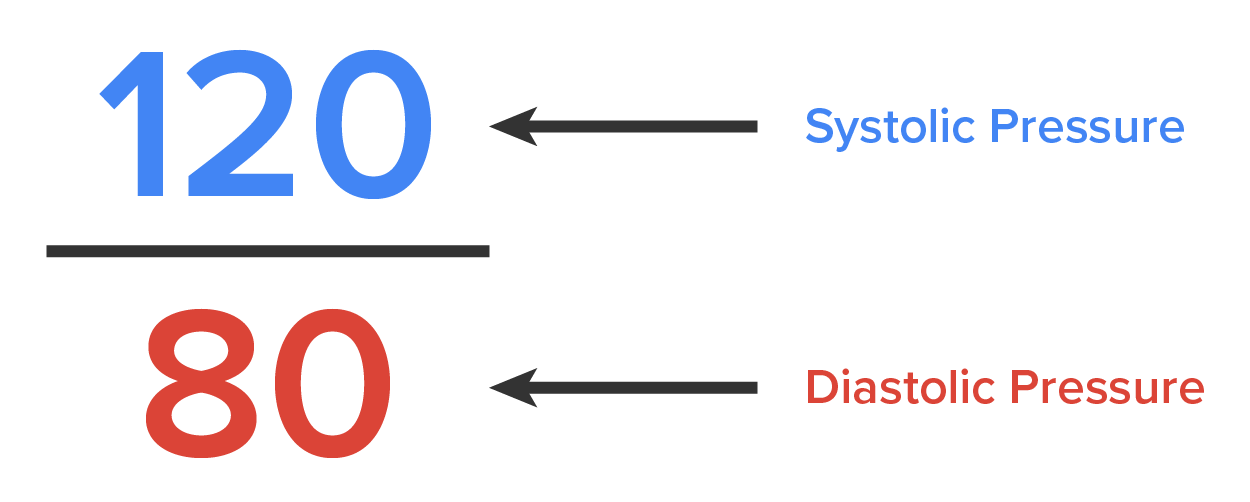

When systemic arterial blood pressure is measured, it is expressed as one number over the other (i.e., 120/80 is a normal adult blood pressure), expressed as systolic pressure over diastolic pressure.

The systolic pressure is the higher value (typically around 120 mm Hg) and reflects the arterial pressure resulting from the ejection of blood during ventricular contraction, or systole. The diastolic pressure is the lower value (usually about 80 mm Hg) and represents the arterial pressure of blood during ventricular relaxation, or diastole.

As shown in the figure above, the difference between the systolic pressure and the diastolic pressure is the pulse pressure. For example, an individual with a systolic pressure of 120 mm Hg and a diastolic pressure of 80 mm Hg would have a pulse pressure of 40 mm Hg.

Generally, a pulse pressure should be at least 25% of the systolic pressure. A pulse pressure below this level is described as low or narrow. This may occur, for example, in patients with a low stroke volume, which may be seen in congestive heart failure, stenosis (stiffening) of the aortic valve, or significant blood loss following trauma. In contrast, a high or wide pulse pressure is common in healthy people following strenuous exercise, when their resting pulse pressure of 30–40 mm Hg may increase temporarily to 100 mm Hg as stroke volume increases. A persistently high pulse pressure at or above 100 mm Hg may indicate excessive resistance in the arteries and can be caused by a variety of disorders. Chronic high resting pulse pressures can degrade the heart, brain, and kidneys, and warrant medical treatment.

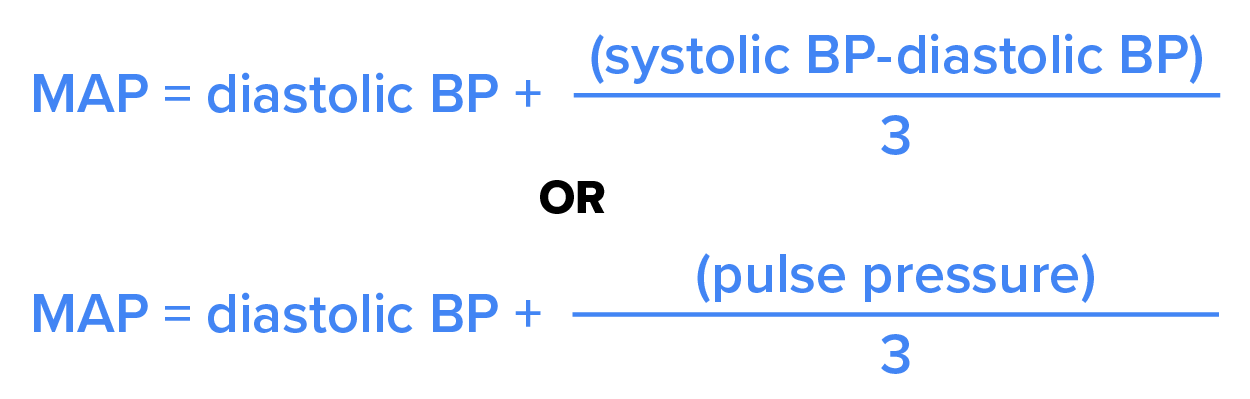

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) represents the “average” pressure of blood in the arteries, that is, the average force driving blood into vessels that serve the tissues. Although complicated to measure directly and complicated to calculate, MAP can be approximated by adding the diastolic pressure to one-third of the pulse pressure or systolic pressure minus the diastolic pressure:

In the figure above, this value is approximately 80 + (120 − 80) / 3, or 93.33. Normally, the MAP falls within the range of 70–110 mm Hg. If the value falls below 60 mm Hg for an extended time, blood pressure will not be high enough to ensure circulation to and through the tissues, which results in ischemia, or insufficient blood flow. The condition hypoxia, inadequate oxygenation of tissues, commonly accompanies ischemia. The term hypoxemia refers to low levels of oxygen in systemic arterial blood. Neurons are especially sensitive to hypoxia (low oxygen levels in the body, not just the blood) and may die or be damaged if blood flow and oxygen supplies are not quickly restored.

In order for blood to flow adequately through the systemic and pulmonary circuit, it must have a sufficient blood pressure. However, if blood pressure exceeds a threshold, it can cause damage to the blood vessels, surrounding tissue, or heart. Therefore, having an abnormally high or low blood pressure can be detrimental.

A chronic and persistent blood pressure measurement of 140/80 mm Hg or above is considered hypertension. Individuals with hypertension have a greater risk for an aneurysm (weakening and bulging of a blood vessel), peripheral arterial disease (obstruction of vessels in peripheral regions of the body), heart attack, stroke, heart failure, or issues with the kidneys, eyes, or memory.

Chronic and persistent blood pressure measurements of 90/60 mm Hg or lower is considered hypotension. Individuals with hypotension have a greater risk of being lightheaded, dizzy, or fatigued, have difficulty with concentration, and are more likely to go into shock.

| Term | Pronunciation | Audio File |

|---|---|---|

| Ischemia | is·che·mia |

|

After blood is ejected from the heart, it enters and expands the elastic arteries. The elastic fibers in the arteries help maintain a high-pressure gradient as they expand to accommodate the blood and then recoil. This expansion and recoiling effect, known as the pulse, can be palpated manually (felt with fingers) or measured electronically. Although the effect diminishes over distance from the heart, elements of the systolic and diastolic components of the pulse are still evident down to the level of the arterioles.

Because pulse indicates heart rate, it is measured clinically to provide clues to a patient’s state of health. It is recorded as beats per minute (bpm). Both the rate and the strength of the pulse are important clinically. The normal range for a pulse is 60 - 100 bpm. A high or irregular pulse rate can be caused by physical activity or other temporary factors, but it may also indicate a heart condition. The pulse strength indicates the strength of ventricular contraction and cardiac output. If the pulse is strong, then systolic pressure is high. If it is weak, systolic pressure has fallen, and medical intervention may be warranted.

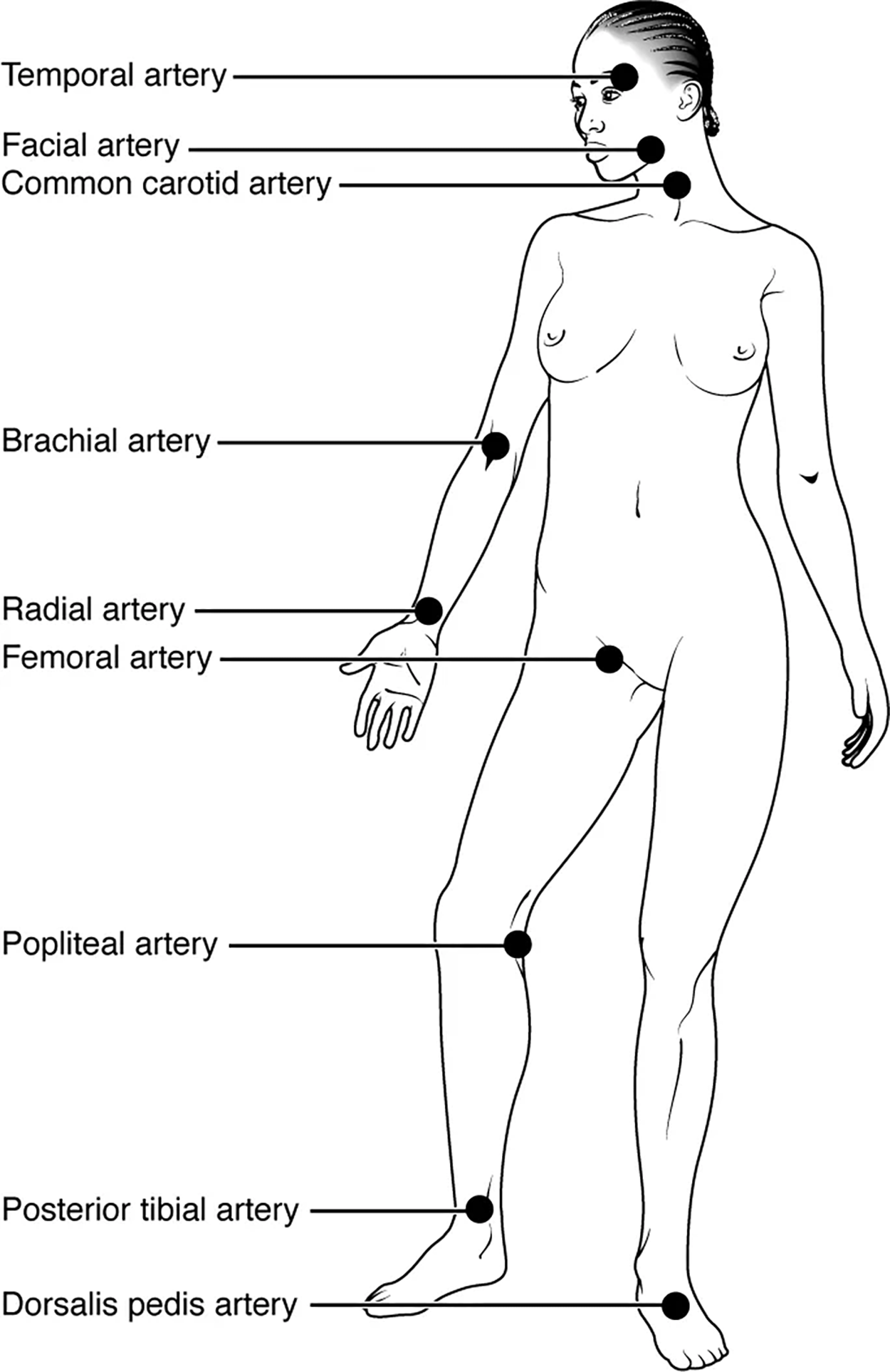

Pulse can be palpated manually by placing the tips of the fingers across an artery that runs close to the body surface and pressing lightly. While this procedure is normally performed using the radial artery in the wrist or the common carotid artery in the neck, any superficial artery that can be palpated may be used (see the images below). Common sites to find a pulse include temporal and facial arteries in the head, brachial arteries in the upper arm, femoral arteries in the thigh, popliteal arteries behind the knees, posterior tibial arteries near the medial tarsal regions, and dorsalis pedis arteries in the feet. A variety of commercial electronic devices are also available to measure pulse.

Blood pressure is one of the critical parameters measured by virtually every patient in every healthcare setting. The technique used today was developed more than 100 years ago by a pioneering Russian physician, Dr. Nikolai Korotkoff. Turbulent blood flow through the vessels can be heard as a soft ticking while measuring blood pressure; these sounds are known as Korotkoff sounds. The technique of measuring blood pressure requires the use of a sphygmomanometer (a blood pressure cuff attached to a measuring device) and a stethoscope. The technique is as follows:

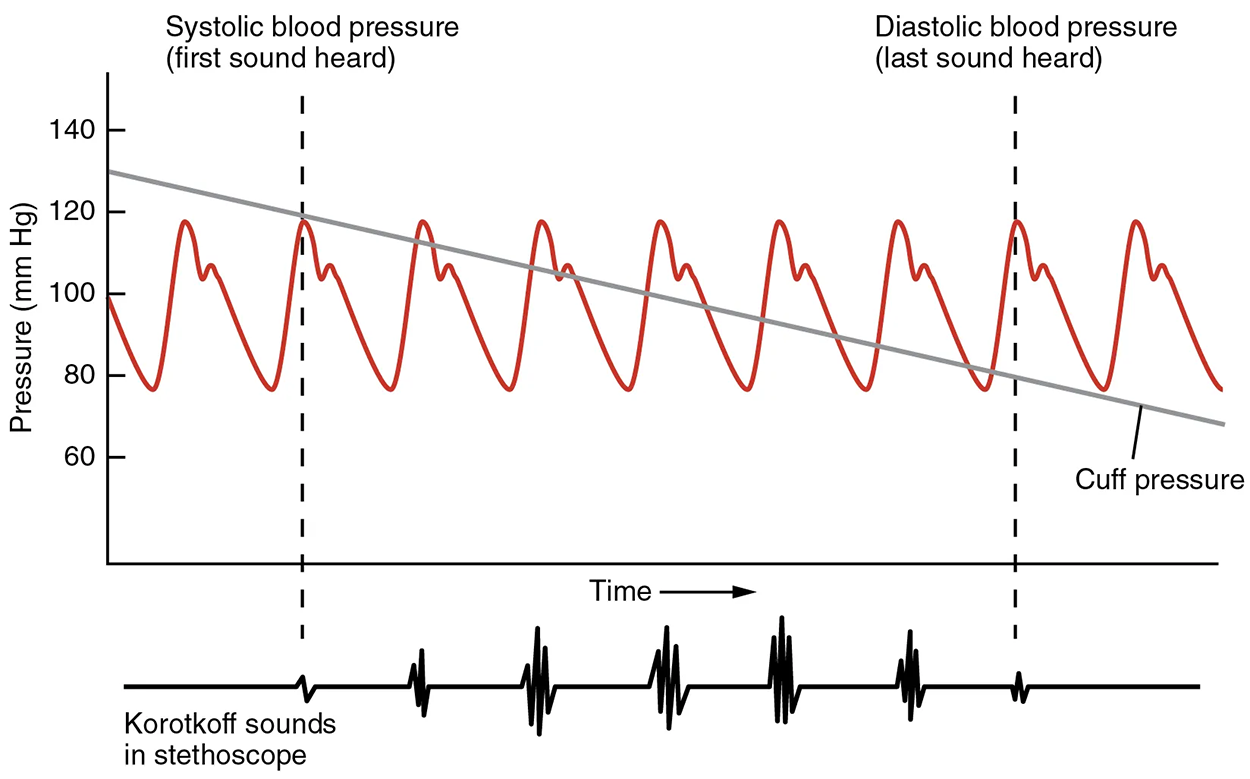

Although there are five recognized Korotkoff sounds, only two are normally recorded. Initially, no sounds are heard since there is no blood flow through the vessels, but as air pressure drops, the cuff relaxes, and blood flow returns to the arm. As shown in the figure below, the first sound heard through the stethoscope—the first Korotkoff sound—indicates systolic pressure. As more air is released from the cuff, blood is able to flow freely through the brachial artery and all sounds disappear. The point at which the last sound is heard is recorded as the patient’s diastolic pressure.

The majority of hospitals and clinics have automated equipment for measuring blood pressure, pulse, and mean arterial pressure that work on the same principles. An even more recent innovation is a small instrument that wraps around a patient’s wrist. The patient then holds the wrist over the heart while the device measures blood flow and records pressure.

| Term | Pronunciation | Audio File |

|---|---|---|

| Korotkoff | Ko·rot·koff |

|

| Sphygmomanometer | sphyg·mo·ma·nom·e·ter |

|

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX "ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E" ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/DETAILS/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL