Table of Contents |

In the last lesson you received an introduction to adenosine triphosphate.

Chemical reactions in metabolic pathways rarely take place spontaneously. Each reaction step is facilitated, or catalyzed, by a protein called an enzyme. Enzymes are important for catalyzing all types of biological reactions: those that require energy as well as those that release energy. Enzymes and coenzymes are important parts of the energy metabolism process. An enzyme can’t function without it’s coenzyme. Many of the coenzymes we need come from B vitamins, this is why we need to eat a variety of foods each day. These pairs help metabolize carbohydrates, fats, and proteins.

IN CONTEXT

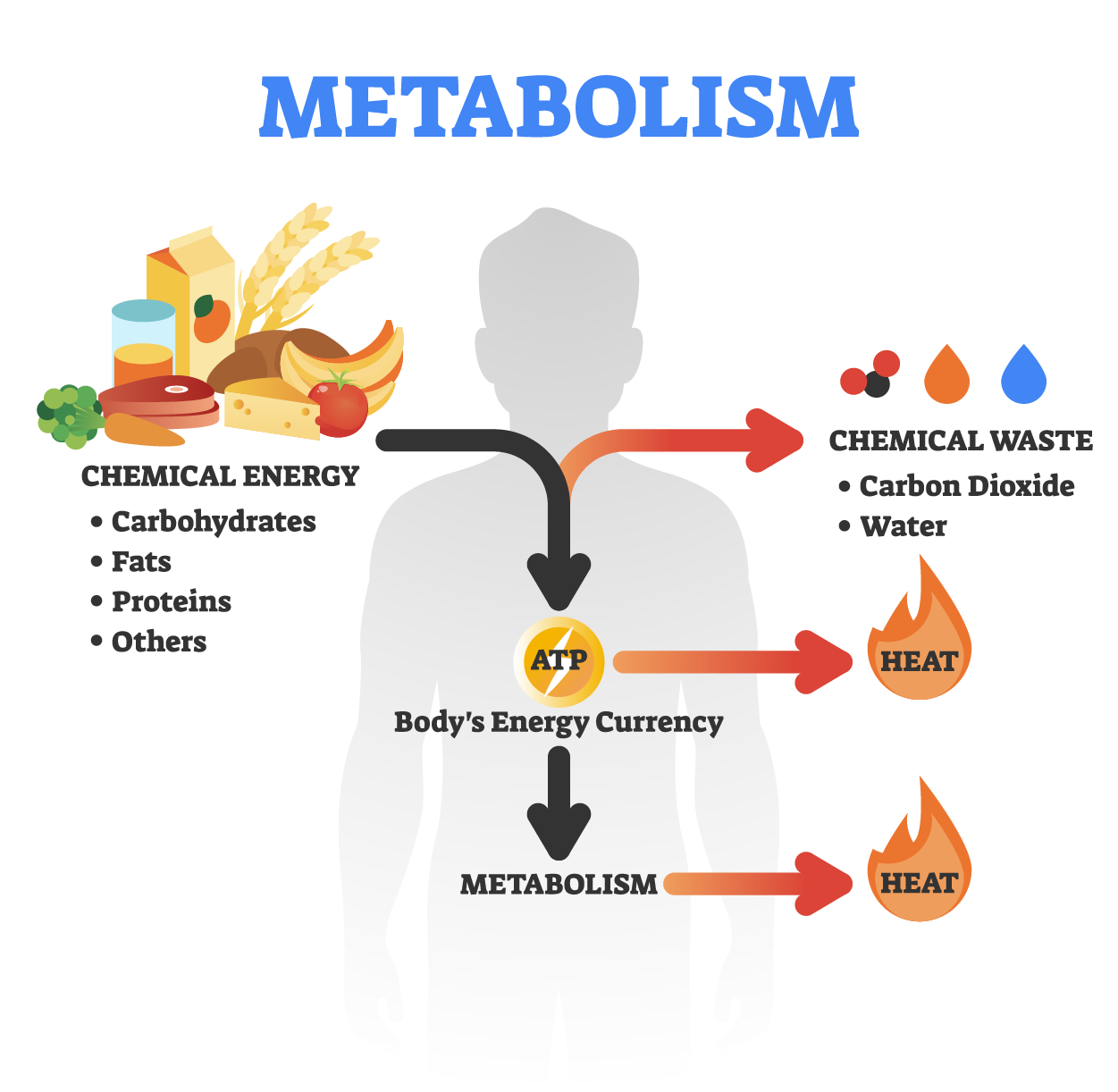

Remember when we learned about digestion, there are three main energy-yielding nutrients which are carbohydrates, fats (lipids), and proteins. These nutrients are made up of smaller molecules that our body can better absorb. Carbohydrates are broken down into glucose and other monosaccharides. Proteins are broken down into amino acids. Fats are broken down into fatty acids and glycerol. Each of these contain oxygen, hydrogen, carbon, and nitrogen. When our bodies use catabolism, the bonds between these atoms break and release energy. Glucose has 6 carbons, glycerol has 3 carbons, fatty acids may have 20 or more carbons, and amino acids may have up to 5 carbons. Depending on how many carbons there are, is how much energy can be provided when the bonds are broken down.

Inside the cell, each sugar molecule is broken down through a complex series of chemical reactions. As chemical energy is released from the bonds in the monosaccharide, it is harnessed to synthesize high-energy adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecules. ATP is the primary energy currency of all cells. Just as the dollar is used as currency to buy goods, cells use molecules of ATP to perform immediate work and power chemical reactions.

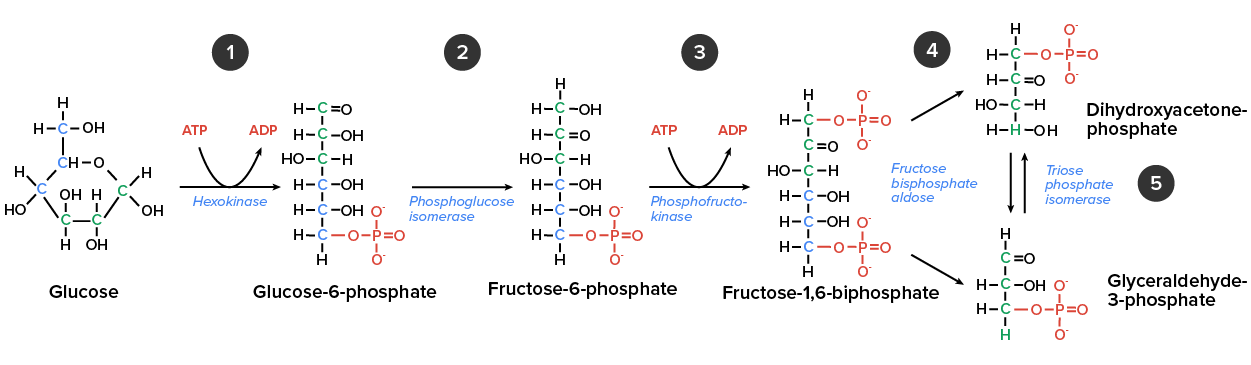

Glycolysis is the first of the main metabolic pathways of cellular respiration to produce energy in the form of ATP. Through two distinct phases, the six-carbon ring of glucose is cleaved into two three-carbon sugars of pyruvate through a series of enzymatic reactions. The first phase of glycolysis requires energy, while the second phase completes the conversion to pyruvate and produces ATP and NADH for the cell to use for energy. Overall, the process of glycolysis produces a net gain of two pyruvate molecules, two ATP molecules, and two NADH molecules for the cell to use for energy. Following the conversion of glucose to pyruvate, the glycolytic pathway is linked to the Krebs Cycle, where further ATP will be produced for the cell’s energy needs. In the first half of glycolysis, energy in the form of two ATP molecules is required to transform glucose into two three-carbon molecules. In the second half of glycolysis, energy is released in the form of 4 ATP molecules and 2 NADH molecules.

So far, glycolysis has cost the cell two ATP molecules and produced two small, three-carbon sugar molecules. Both of these molecules will proceed through the second half of the pathway, where sufficient energy will be extracted to pay back the two ATP molecules used as an initial investment while also producing a profit for the cell of two additional ATP molecules and two even higher-energy NADH molecules.

One glucose molecule produces four ATP, two NADH, and two pyruvate molecules during glycolysis.

As the molecules start to break down, pyruvate and acetyl-CoA are needed. Pyruvate is the end-product of glycolysis. Acetyl-CoA (acetyl coenzyme A) is a molecule that conveys the carbon atoms from glycolysis (pyruvate) to the citric acid cycle to be oxidized for energy production. In the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA, each pyruvate molecule loses one carbon atom with the release of carbon dioxide. During the breakdown of pyruvate, electrons are transferred to NAD+ to produce NADH, which will be used by the cell to produce ATP.

After glycolysis, pyruvate is converted into acetyl-CoA in order to enter the citric acid cycle. In order for pyruvate, the product of glycolysis, to enter the next pathway, it must undergo several changes to become acetyl Coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA). Acetyl-CoA is a molecule that is further converted to oxaloacetate, which enters the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle). The conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA is a three-step process. The acetyl carbons of acetyl-CoA are released as carbon dioxide in the citric acid cycle. Acetyl-CoA links glycolysis and pyruvate oxidation with the citric acid cycle. In the presence of oxygen, acetyl-CoA delivers its acetyl group to a four-carbon molecule, oxaloacetate, to form citrate, a six-carbon molecule with three carboxyl groups. During this first step of the citric acid cycle, the CoA enzyme, which contains a sulfhydryl group (-SH), is recycled and becomes available to attach another acetyl group. The citrate will then harvest the remainder of the extractable energy from what began as a glucose molecule and continue through the citric acid cycle.

In the citric acid cycle, the two carbons that were originally the acetyl group of acetyl-CoA are released as carbon dioxide, one of the major products of cellular respiration, through a series of enzymatic reactions. For each acetyl-CoA that enters the citric acid cycle, two carbon dioxide molecules are released in reactions that are coupled with the production of NADH molecules from the reduction of NAD+ molecules.

Like the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA, the citric acid cycle takes place in the matrix of the mitochondria. Almost all of the enzymes of the citric acid cycle are soluble, with the single exception of the enzyme succinate dehydrogenase, which is embedded in the inner membrane of the mitochondrion. Unlike glycolysis, the citric acid cycle is a closed loop: the last part of the pathway regenerates the compound used in the first step. The eight steps of the cycle are a series of redox, dehydration, hydration, and decarboxylation reactions that produce two carbon dioxide molecules, one GTP/ATP, and reduced forms of NADH and FADH2. This is considered an aerobic pathway because the NADH and FADH2 produced must transfer their electrons to the next pathway in the system, which will use oxygen. If this transfer does not occur, the oxidation steps of the citric acid cycle also do not occur.

Two carbon atoms come into the citric acid cycle from each acetyl group, representing four out of the six carbons of one glucose molecule. Two carbon dioxide molecules are released on each turn of the cycle; however, these do not necessarily contain the most recently-added carbon atoms. The two acetyl carbon atoms will eventually be released on later turns of the cycle; thus, all six carbon atoms from the original glucose molecule are eventually incorporated into carbon dioxide. Each turn of the cycle forms three NADH molecules and one FADH2 molecule. These carriers will connect with the last portion of aerobic respiration to produce ATP molecules. One GTP or ATP is also made in each cycle. Several of the intermediate compounds in the citric acid cycle can be used in synthesizing non-essential amino acids; therefore, the cycle is amphibolic (both catabolic and anabolic).

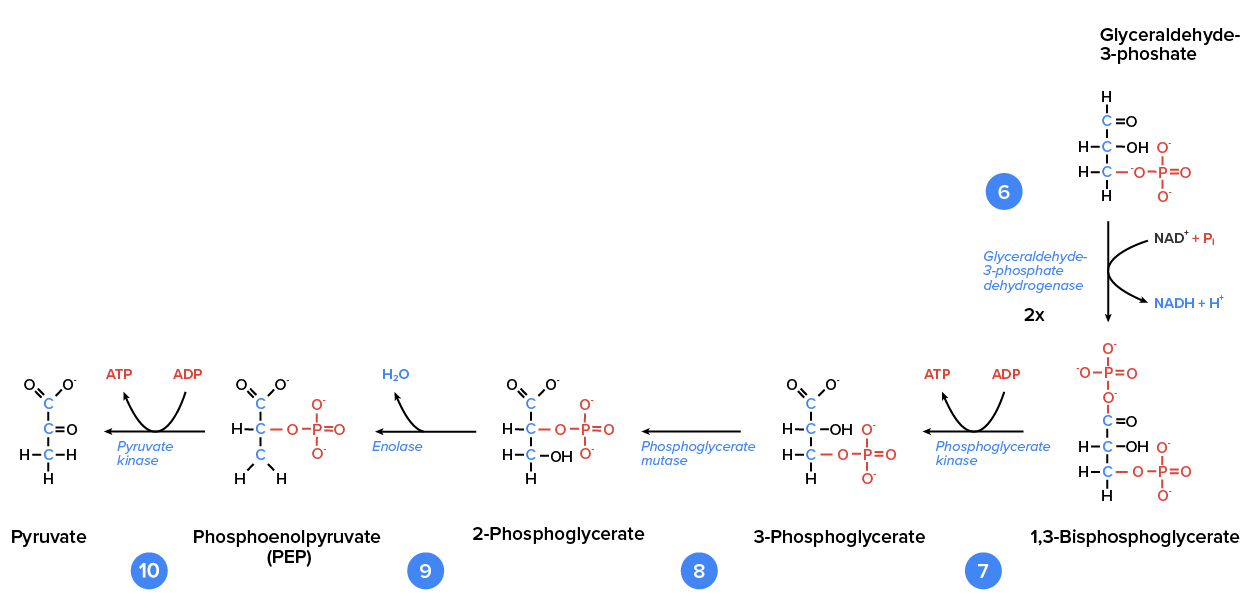

The electron transport chain uses the electrons from electron carriers to create a chemical gradient that can be used to power oxidative phosphorylation. Oxidative phosphorylation is a highly efficient method of producing large amounts of ATP, the basic unit of energy for metabolic processes. During this process electrons are exchanged between molecules, which creates a chemical gradient that allows for the production of ATP. The most vital part of this process is the electron transport chain, which produces more ATP than any other part of cellular respiration.

The electron transport chain is the final component of aerobic respiration and is the only part of glucose metabolism that uses atmospheric oxygen. Electron transport is a series of redox reactions that resemble a relay race. Electrons are passed rapidly from one component to the next to the endpoint of the chain, where the electrons reduce molecular oxygen, producing water. This requirement for oxygen in the final stages of the chain can be seen in the overall equation for cellular respiration, which requires both glucose and oxygen. Another factor that affects the yield of ATP molecules generated from glucose is the fact that intermediate compounds in these pathways are used for other purposes. Glucose catabolism connects with the pathways that build or break down all other biochemical compounds in cells, but the result is not always ideal.

EXAMPLE

Sugars other than glucose are fed into the glycolytic pathway for energy extraction. Moreover, the five-carbon sugars that form nucleic acids are made from intermediates in glycolysis. Certain nonessential amino acids can be made from intermediates of both glycolysis and the citric acid cycle. Lipids, such as cholesterol and triglycerides, are also made from intermediates in these pathways, and both amino acids and triglycerides are broken down for energy through these pathways. Overall, in living systems, these pathways of glucose catabolism extract about 34 percent of the energy contained in glucose.Anaerobic respiration is a type of respiration where oxygen is not used; instead, organic or inorganic molecules are used as final electron acceptors. The production of energy requires oxygen. The electron transport chain, where the majority of ATP is formed, requires a large input of oxygen. However, many organisms have developed strategies to carry out metabolism without oxygen or can switch from aerobic to anaerobic cell respiration when oxygen is scarce.

During cellular respiration, some living systems use an organic molecule as the final electron acceptor. Processes that use an organic molecule to regenerate NAD+ from NADH are collectively referred to as fermentation. In contrast, some living systems use an inorganic molecule as a final electron acceptor. Both methods are called anaerobic cellular respiration, where organisms convert energy for their use in the absence of oxygen.

The fermentation method used by animals and certain bacteria (like those in yogurt) is called lactic acid fermentation. This type of fermentation is used routinely in mammalian red blood cells and in skeletal muscle that has an insufficient oxygen supply to allow aerobic respiration to continue (that is, in muscles used to the point of fatigue). The excess amount of lactate in those muscles is what causes the burning sensation in your legs while running. This pain is a signal to rest the overworked muscles so they can recover. In these muscles, lactic acid accumulation must be removed by the blood circulation and the lactate brought to the liver for further metabolism.

IN CONTEXT

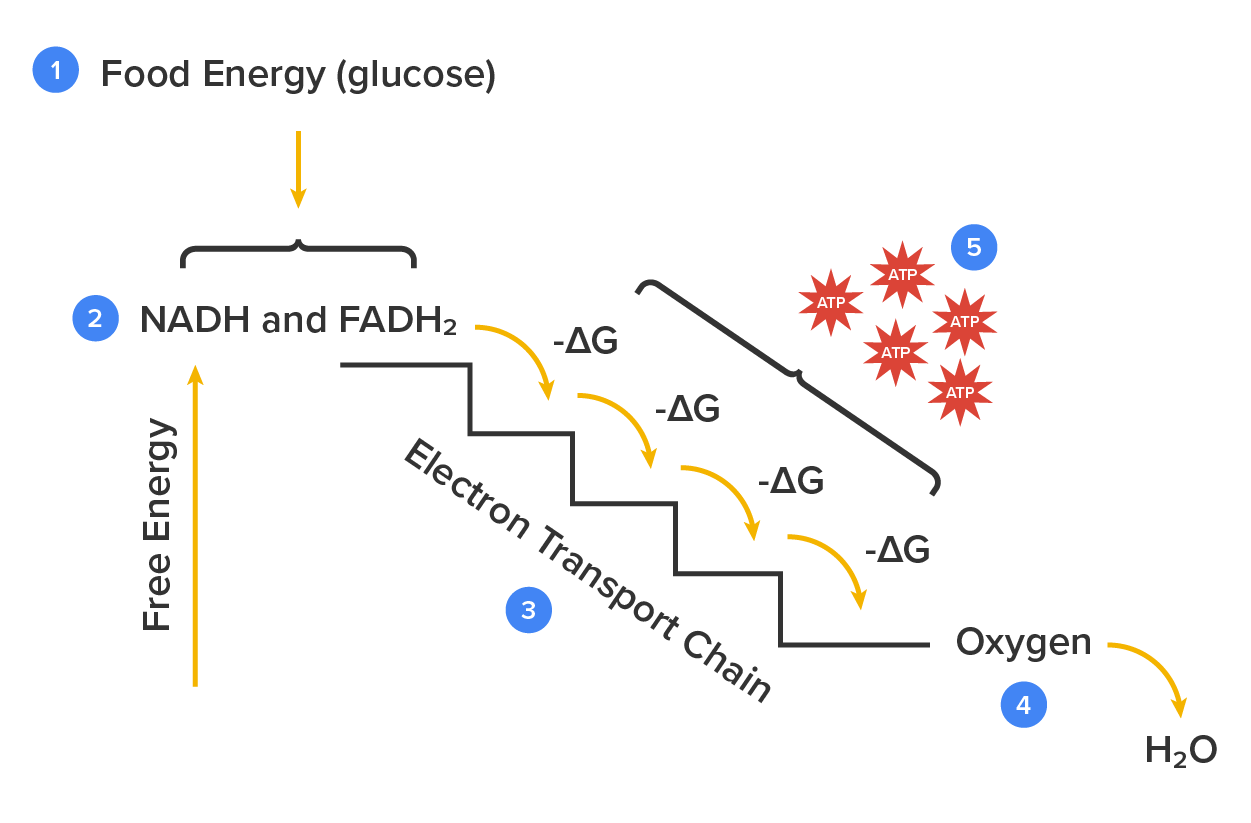

You have learned about the catabolism of glucose, which provides energy to living cells. But living things consume more than glucose for food. How does a turkey sandwich end up as ATP in your cells? This happens because all of the catabolic pathways for carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids eventually connect into glycolysis and the citric acid cycle pathways. Metabolic pathways should be thought of as porous; that is, substances enter from other pathways, and intermediates leave for other pathways. These pathways are not closed systems. Many of the substrates, intermediates, and products in a particular pathway are reactants in other pathways. Like sugars and amino acids, the catabolic pathways of lipids are also connected to the glucose catabolism pathways.

Glycogen, a polymer of glucose, is an energy-storage molecule in animals. When there is adequate ATP present, excess glucose is shunted into glycogen for storage. Glycogen is made and stored in both the liver and muscles. The glycogen is hydrolyzed into the glucose monomer, glucose-1-phosphate (G-1-P), if blood sugar levels drop. The presence of glycogen as a source of glucose allows ATP to be produced for a longer period of time during exercise. Glycogen is broken down into G-1-P and converted into glucose-6-phosphate (G-6-P) in both muscle and liver cells; this product enters the glycolytic pathway.

Excess amino acids are converted into molecules that can enter the pathways of glucose catabolism. Amino acids must be deaminated before entering any of the pathways of glucose catabolism: the amino group is converted to ammonia, which is used by the liver in the synthesis of urea. Proteins are hydrolyzed by a variety of enzymes in cells. Most of the time, the amino acids are recycled into the synthesis of new proteins or are used as precursors in the synthesis of other important biological molecules, such as hormones, nucleotides, or neurotransmitters. However, if there are excess amino acids, or if the body is in a state of starvation, some amino acids will be shunted into the pathways of glucose catabolism. When deaminated, amino acids can enter the pathways of glucose metabolism as pyruvate, acetyl-CoA, or several components of the citric acid cycle.

EXAMPLE

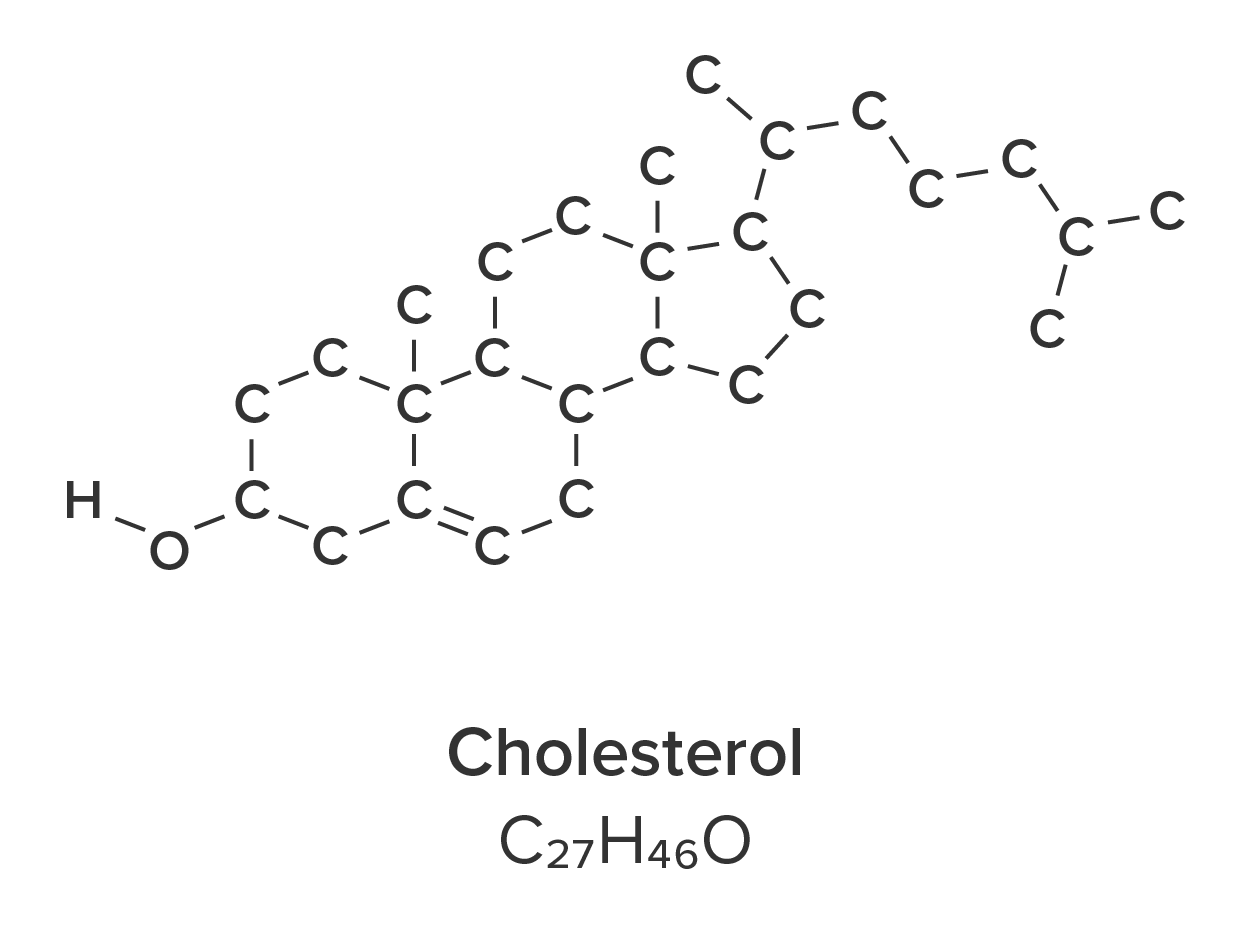

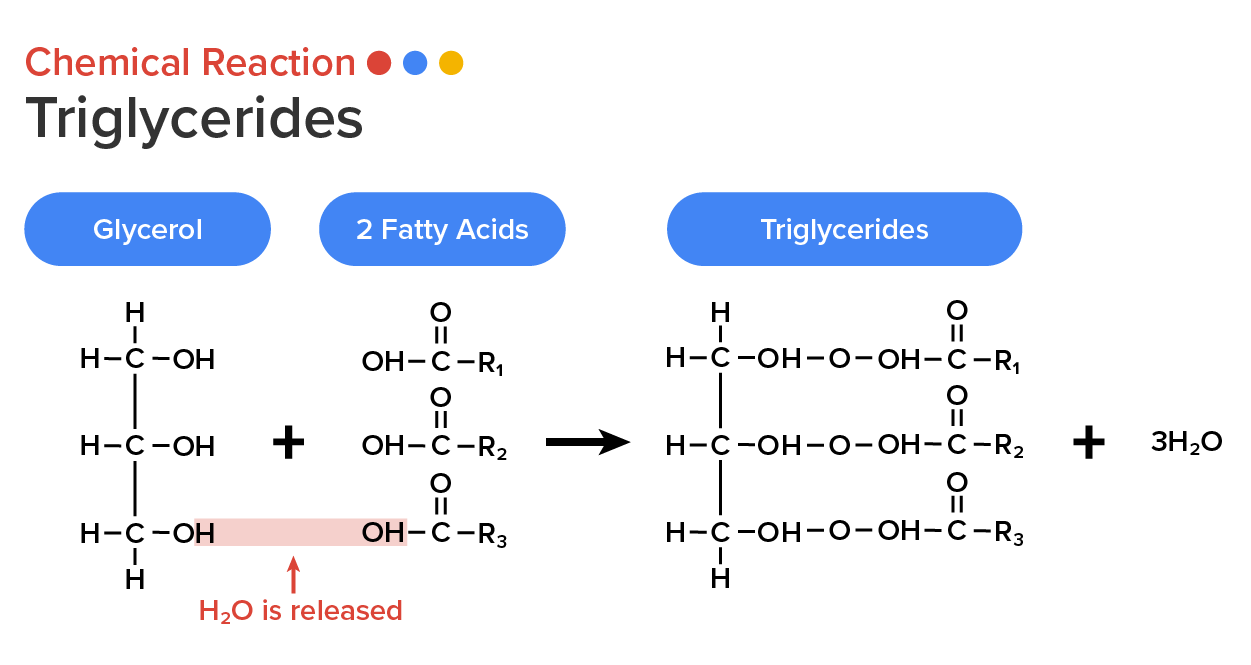

Deamidated asparagine and aspartate are converted into oxaloacetate and enter glucose catabolism in the citric acid cycle. Deaminated amino acids can also be converted into another intermediate molecule before entering the pathways. Several amino acids can enter glucose catabolism at multiple locations.Lipids can be both made and broken down through parts of the glucose catabolism pathways. Like sugars and amino acids, the catabolic pathways of lipids are also connected to the glucose catabolism pathways. The lipids that are connected to the glucose pathways are cholesterol and triglycerides.

Cholesterol contributes to cell membrane flexibility and is a precursor to steroid hormones. The synthesis of cholesterol starts with acetyl groups, which are transferred from acetyl-CoA, and proceeds in only one direction; the process cannot be reversed. Thus, synthesis of cholesterol requires an intermediate of glucose metabolism.

Triglycerides, a form of long-term energy storage in animals, are made of glycerol and three fatty acids. Animals can make most of the fatty acids they need. Triglycerides can be both made and broken down through parts of the glucose catabolism pathways. Glycerol can be phosphorylated to glycerol-3-phosphate, which continues through glycolysis.

Fatty acids are catabolized in a process called beta-oxidation that takes place in the matrix of the mitochondria and converts their fatty acid chains into two carbon units of acetyl groups, while producing NADH and FADH2. The acetyl groups are picked up by CoA to form acetyl-CoA that proceeds into the citric acid cycle as it combines with oxaloacetate. The NADH and FADH2 are then used by the electron transport chain.

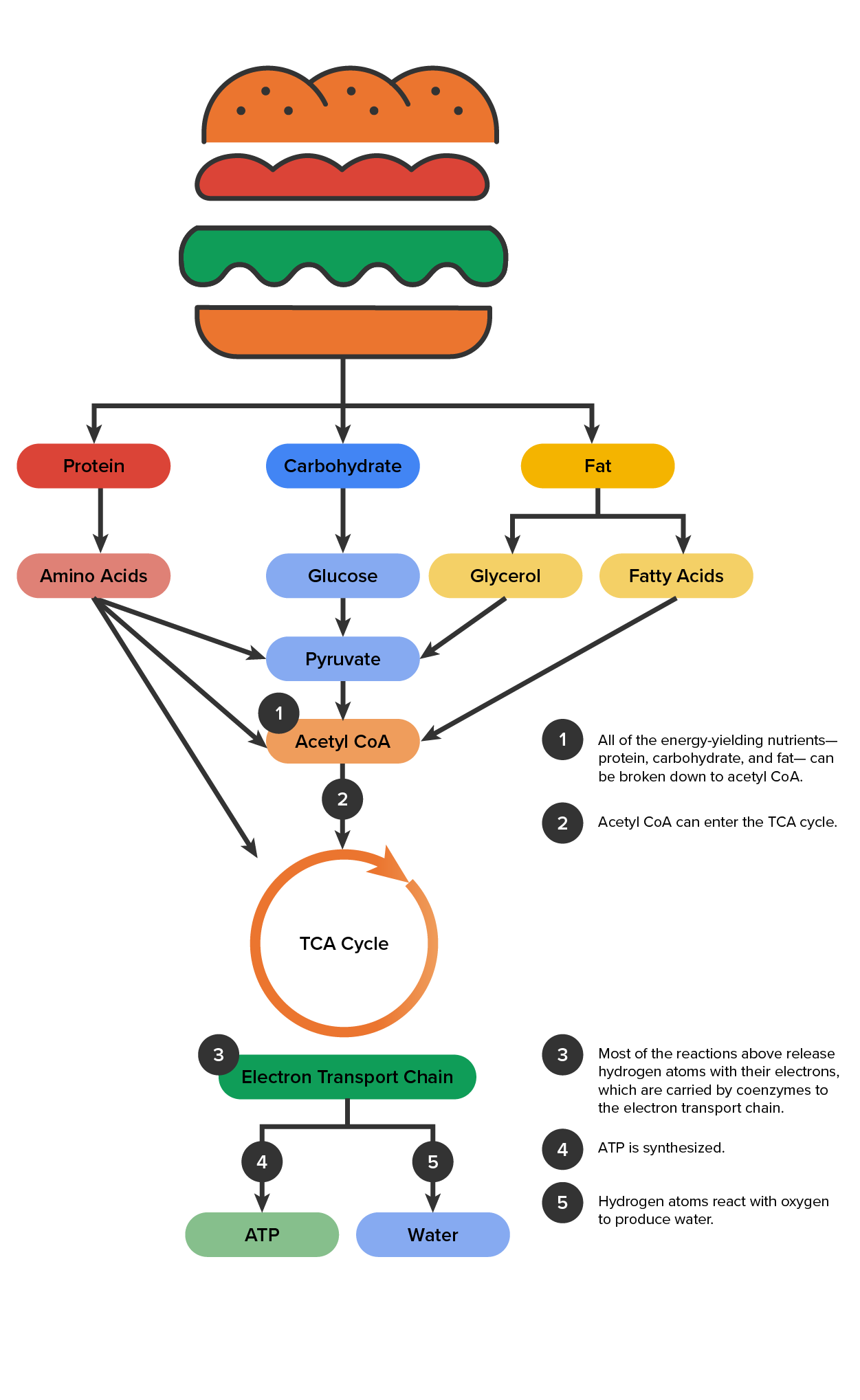

In summary, in order for our bodies to break down food, we have to eat food. To help understand the concept of energy metabolism and what happens when we eat food, we are going to use the example of a cheeseburger.

A cheeseburger has a bun, a beef patty, and a slice of cheese. These cheeseburger parts contain three macronutrients; carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. Carbohydrates are the macronutrient that provides the most energy, and is the primary source of energy for the brain. Typical sources of carbohydrates include breads, like the cheeseburger bun, pasta, rice, fruits and vegetables. Carbohydrates start their process of breaking down within the mouth through chewing and enzymes in the mouth. When carbohydrates are broken down, they turn into glucose. Glucose is the main type of simple sugar and what our bodies take and recognize the most as energy. Protein is the next macronutrient that provides energy.

Protein helps provide structure and function to the cells throughout the body. Protein can be found within animal products such as chicken, beef, turkey, pork, cheese, as well as plant based sources like beans, lentils, tofu, milk. When protein is first digested, it is broken down into amino acids. Amino acids are the building blocks of cells and are essential for energy and daily life. Proteins are broken down within the stomach and the small intestine. The beef patty contains proteins that will be broken down into the amino acids.

Fat is the last macronutrient, and fat is the most energy-dense nutrient. Fat plays a vital role in many processes such as providing energy, protecting organs within the body, cell growth, and aids in vitamin absorption. Sources of fat can be found in many foods and is typically accompanied with another macronutrient. Examples of fat food sources are olive oil, or any vegetable oil, dairy products, fish, nuts and seeds. In the example of the cheeseburger, the cheese slice is a source of fat, as well as the burger patty, and the bun contains fat as well. When fat is broken down it turns into glycerol, and fatty acids. Glycerol is an alcohol that plays a role in energy yielding processes. Fatty acids are the building blocks of our fat and are absorbed into the bloodstream for energy storage.

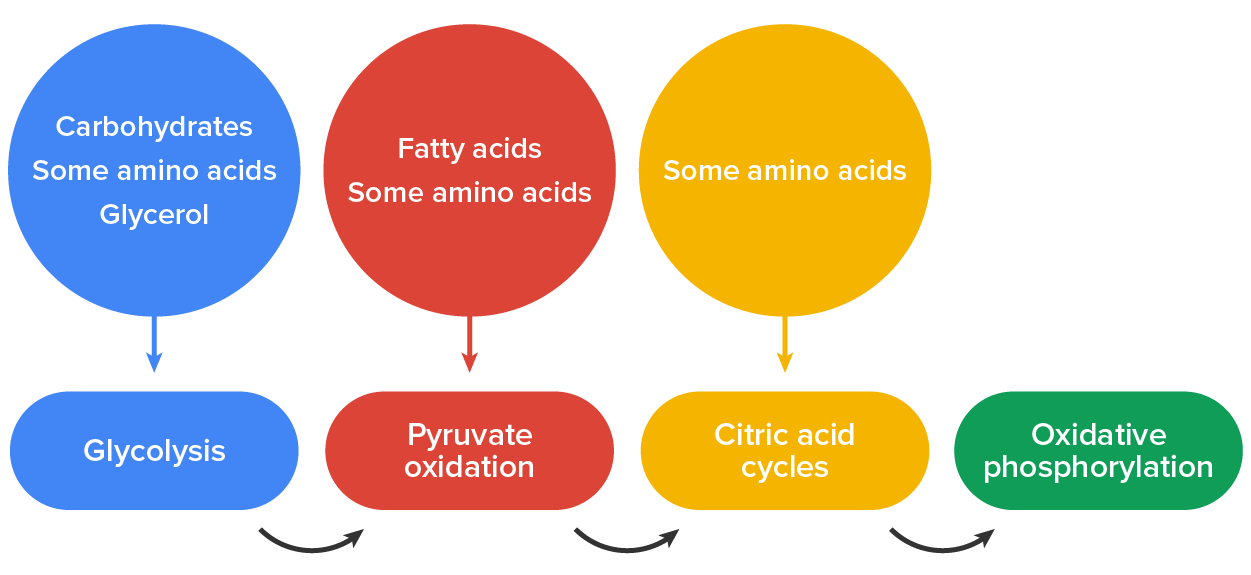

Once carbohydrates are broken down into glucose, and protein is broken down into amino acids, and fat is broken into glycerol and fatty acids, these all turn into pyruvate. Pyruvate then turns into acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA enters a cycle known as the TCA cycle and the electron transport chain. These cycles result in ATP, and water and carbon dioxide. The ATP is our body's form of energy that all cells can use. Water is necessary for the body to function, regulate body temperature, lubricate joints, and transport throughout the body. The body also takes the carbon dioxide and uses it to regulate and control other functions within the body. Overall, all food gets broken down into macronutrients, and through the complex process of digestion and metabolism, turn into ATP, water, and carbon dioxide for energy.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM LUMEN LEARNING’S “NUTRITION FLEXBOOK”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-nutrition/. LICENSE: creative commons attribution 4.0 international.

REFERENCES

Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (n.d.). Adenosine triphosphate. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved May 21, 2022, from www.britannica.com/science/adenosine-triphosphate

Energy metabolism. Energy Metabolism - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.). Retrieved May 23, 2022, from www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/energy-metabolism