Table of Contents |

To begin with, recall that virtue-based ethics is an ethical theory maintaining that an action is to be evaluated based on how that action informs the aspects of the agent's character.

The character traits of an agent are seen as either morally good or bad—they are called virtues and vices, respectively. Traditionally, traits such as patience, courage, generosity, and honesty are seen as virtues; while traits such as impatience, cowardice, greed, and dishonesty are seen as vices.

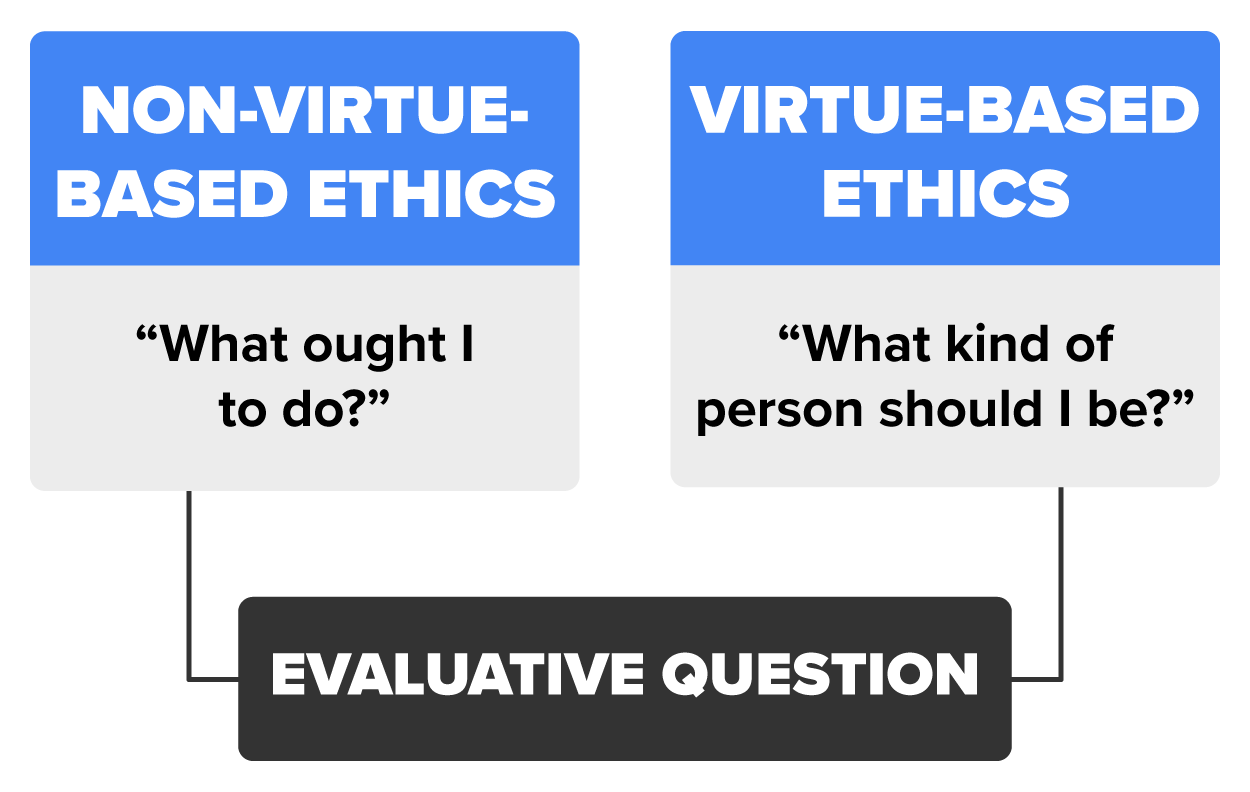

Because of the emphasis on character, the kind of question you would ask yourself in virtue-based ethics is different from the kind that you would ask if you were primarily concerned with evaluating actions.

Sometimes our everyday understanding of right and wrong agrees with virtue-based ethics.

EXAMPLE

Most of us think we should be friendly to people, rather than rude or dismissive. Friendliness is a virtue, so being friendly to people is obligatory.Helping out your friends is generally seen as a good thing. Virtue-based ethics agrees with this when it’s a manifestation of the virtue of friendship or generosity. However, there are other examples where we would normally disagree with virtue-based ethics. This can perhaps be seen most clearly in cases involving virtues that we normally consider outside the scope of ethics.

EXAMPLE

Sometimes wit or good humor is listed as a virtue. Being a good conversationalist entails being neither a buffoon nor austere, but knowing how to share a joke and listen well to other people. Most of us appreciate a witty person, but we don’t usually think that it’s a moral obligation to be like this.Something similar can be said of virtues such as confidence. Again, you might think this is a good trait to have for many reasons, but you probably don’t see it as a morally obligatory trait.

Sometimes, it’s not clear if your everyday views of right and wrong agree with virtue-based ethics. One reason is that it’s difficult to discern someone’s character from their actions.

As you can see, if you don’t know the reason for the action, it’s difficult to know if it really does indicate a certain character trait. We certainly tend to think charity is good, but if we can’t be sure that it expresses a virtue, then it can’t be said to be good from the perspective of virtue-based ethics.

There are many other similar cases where this kind of ambiguity comes up.

EXAMPLE

Say you see a politician exposing the corruption within her party. You might think that this is someone being honest, but she could equally have had an ulterior motive—perhaps she advanced her career by telling the truth.We generally think telling the truth is a good thing, but in this case, the virtue-based ethical theorist wouldn’t necessarily agree. They would need to know what kind of person was being truthful and for what reasons.

Philosophers working in ethics often try to apply ethical theories to specific situations. Let’s consider how the following issues would be evaluated from the perspective of virtue-based ethics: