Table of Contents |

In another lesson, you learned about “-static” versus “-cidal” chemicals. These terms can also be applied to antimicrobial drugs.

Drugs described as “-static,” such as bacteriostatic medications, inhibit growth, but growth resumes once the drug is no longer present. In many cases, this is sufficient for a patient’s immune system to fight off an infection.

Drugs described as “-cidal,” such as bactericidal medications, kill their target bacteria. These medications may be necessary if patients are immunocompromised for some reason (such as serious illness or cancer treatment) or for particularly dangerous infections (such as acute endocarditis, which is an infection of the lining of the heart).

Another important consideration in choosing an antimicrobial drug therapy is the spectrum of activity of the medication. Broad-spectrum antimicrobials target a wide range of bacterial pathogens. This can be helpful if the exact pathogen is unknown, there is a need for treatment before waiting for laboratory confirmation of the pathogen, or an infection is caused by multiple pathogens. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are also useful as prophylactic treatments when there is a risk of infection (e.g., during surgery) rather than a specific pathogen to target.

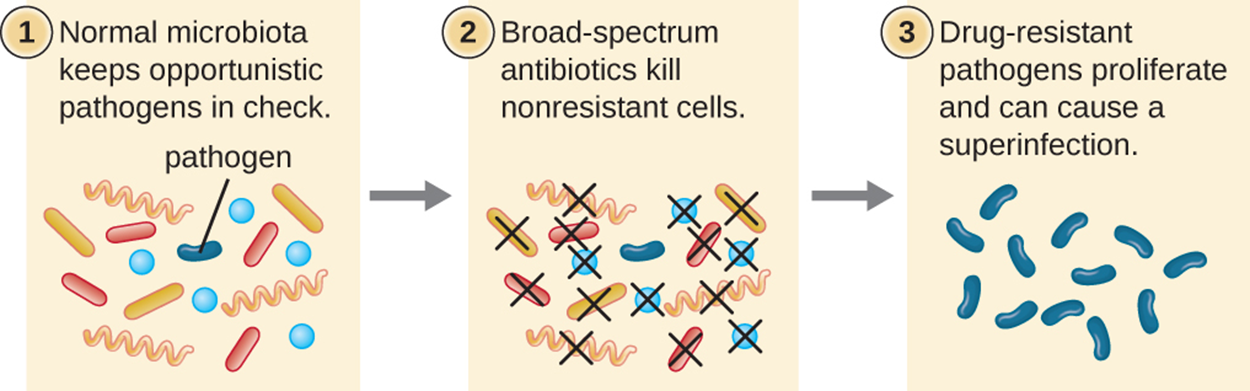

Narrow-spectrum antimicrobials target a specific subset of pathogens. For example, a particular medication might target only gram-positive or only gram-negative bacteria. A major advantage of using narrow-spectrum antimicrobials is that it affects the pathogen without targeting other bacteria. Humans have many microbes that live naturally on the body (the normal microbiota), especially on the skin and in the digestive tract. Using narrow-spectrum antimicrobials reduces the risk that the normal microbiota will be harmed and reduces the likelihood of causing bacterial species that survive treatment to become resistant to the antibiotic.

When the normal microbiota is killed, there is an increased risk of superinfection (a secondary infection in a patient who already has an infection). The normal microbiota helps to prevent colonization by pathogens. If the normal microbiota is damaged, the risk of secondary infections increases. For example, the pathogen Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile causes potentially dangerous intestinal infections associated with antibiotic use.

The image and steps below show how broad-spectrum antimicrobial use can lead to superinfection.

Other considerations during treatment are dosage and route of administration, which are interrelated. Dosage is the amount of medication given during a certain time interval. Route of administration is the method used to introduce a drug into the body.

To determine the correct dosage, it is necessary to consider how much medication a person needs to take to achieve optimal therapeutic levels of the drug where it is needed. Different medications are associated with different adverse events (side effects), such as nausea or allergic reactions. The types of adverse events vary widely, and you will learn more about the potentially problematic effects of medications in other lessons. Some of these effects are minor and tolerable, whereas others may be dangerous. Therefore, it is important to balance providing enough medication to produce the desired effects while minimizing the risk of negative effects.

There are factors that influence therapeutic levels in individuals, such as differences in metabolism, medical conditions, and interactions with other medications. Both the amount of medication per dose and the timing of doses must be considered. In children, a dose is often based on mass. Smaller children may need very different dosages from larger children because of their size and metabolic considerations, among other factors. For adults and individuals aged 12 or older, there is typically a standard dosage recommendation. However, adults can vary in size as well, and some experts argue that this should be considered more often.

Medications can be metabolized and eliminated by the body in multiple ways, but the liver and kidneys often play important roles. Therefore, particular care is needed when treating individuals with liver or kidney disease or dysfunction. If an individual cannot metabolize or excrete a medication as rapidly as expected, then the result may be higher levels of medication in the body and an increased risk of negative effects. Some medications may also increase the risk of harm to the liver and kidneys.

Another important consideration is the half-life of a medication, which is the rate at which 50% of the drug is eliminated from the body. Medications with short half-lives may need to be taken more frequently than medications with long half-lives to maintain a steady concentration. Medications with longer half-lives may be more convenient but may also cause negative effects that take longer to resolve after the medication is discontinued.

For some medications, dose or timing may be particularly important. Some drugs are more effective when administered in large doses to provide high levels for a short time at the site of infection. Other medications are more effective when lower levels are maintained over a longer period of time.

The route of administration is another important consideration. It can be convenient to take medications orally as pills, capsules, or liquids. However, some drugs are not absorbed easily through the gastrointestinal tract or may be inactivated by digestive enzymes. Some medications are most effective when applied topically. This method is often used to treat skin infections to which an ointment or cream may be applied. Parenteral routes (which avoid passage through the gastrointestinal tract) include injections. These are preferred when patients cannot take oral medication (e.g., because of vomiting) or are not absorbed well through the digestive tract.

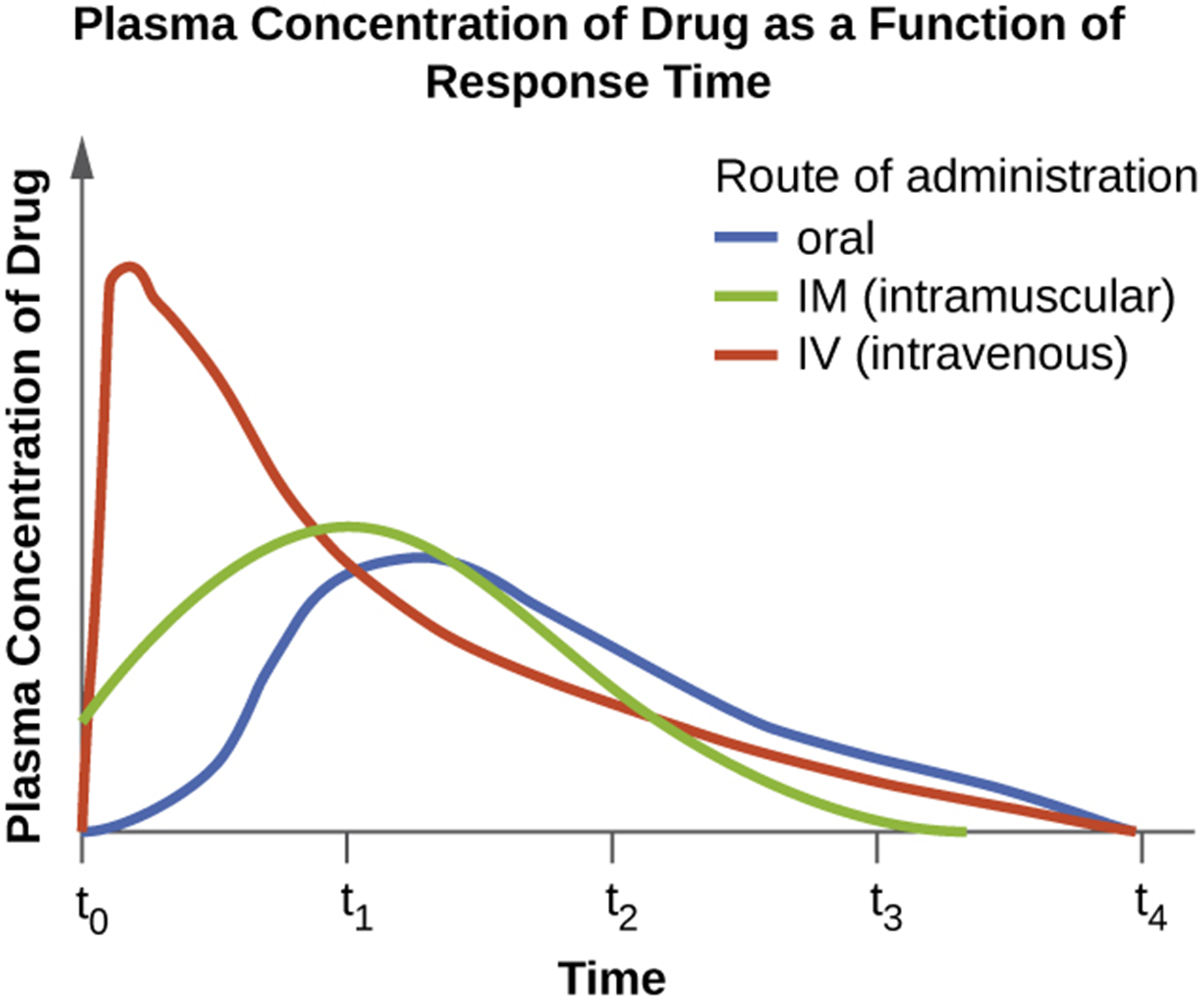

As shown in the graph below, parenteral methods (including intramuscular and intravenous injections) typically produce higher plasma concentrations of a medication more rapidly than oral routes. This may also be an important consideration in choosing a route of administration.

In addition to the factors already described, drug interactions are an essential consideration in choosing a medication. In some cases, two medications are used simultaneously to achieve a better outcome (a synergistic effect). The combination of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (two antibiotics) produces a bactericidal instead of the bacteriostatic effect that each has separately.

However, two medications may also interact in a negative way (an antagonistic effect). This type of interaction can occur between any combination of medications, regardless of whether one, both, or neither is an antimicrobial medication. Antagonistic effects can make medications less effective by lowering therapeutic levels because of increased metabolism and elimination. Alternatively, they may increase the risk of toxicity because of reduced metabolism and elimination. Some medications may have similar negative effects, worsening the overall risk and severity of those effects. Some medications, such as antacids, affect the pH in the stomach, which may reduce the absorption of other medications. There is some evidence that some antimicrobials may reduce the effectiveness of oral contraceptive medications. These and other types of interactions must be carefully considered when medications are chosen.

As patients age, they may take multiple medications (polypharmacy), and this can make medication selection complex (e.g., Masnoon, 2017). For this reason, keeping careful track of medications and dosages can be very helpful when patients discuss treatments with their doctors.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “MICROBIOLOGY.” ACCESS FOR FREE AT openstax.org/details/books/microbiology. LICENSE: CC ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

Masnoon, N., Shakib, S., Kalisch-Ellett, L., & Caughey, G. E. (2017). What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC geriatrics, 17(1), 230. doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2