Table of Contents |

Chyme released from the stomach enters the small intestine, which is the primary digestive organ in the body. Not only is this where most digestion occurs, it is also where practically all absorption occurs.

Being the longest part of the alimentary canal, the small intestine is about 3.05 meters (10 feet) long in a living person (but about twice as long in a cadaver due to the loss of muscle tone). Since this makes it about five times longer than the large intestine, you might wonder why it is called “small.” In fact, its name derives from its relatively smaller diameter of only about 2.54 cm (1 in), compared with 7.62 cm (3 in) for the large intestine. As we’ll see shortly, in addition to its

length, the folds and projections of the lining of the small intestine work to give it an enormous surface area, which is approximately 200 m², more than 100 times the surface area of your skin. This large surface area is necessary for complex processes of digestion and absorption that occur within it.

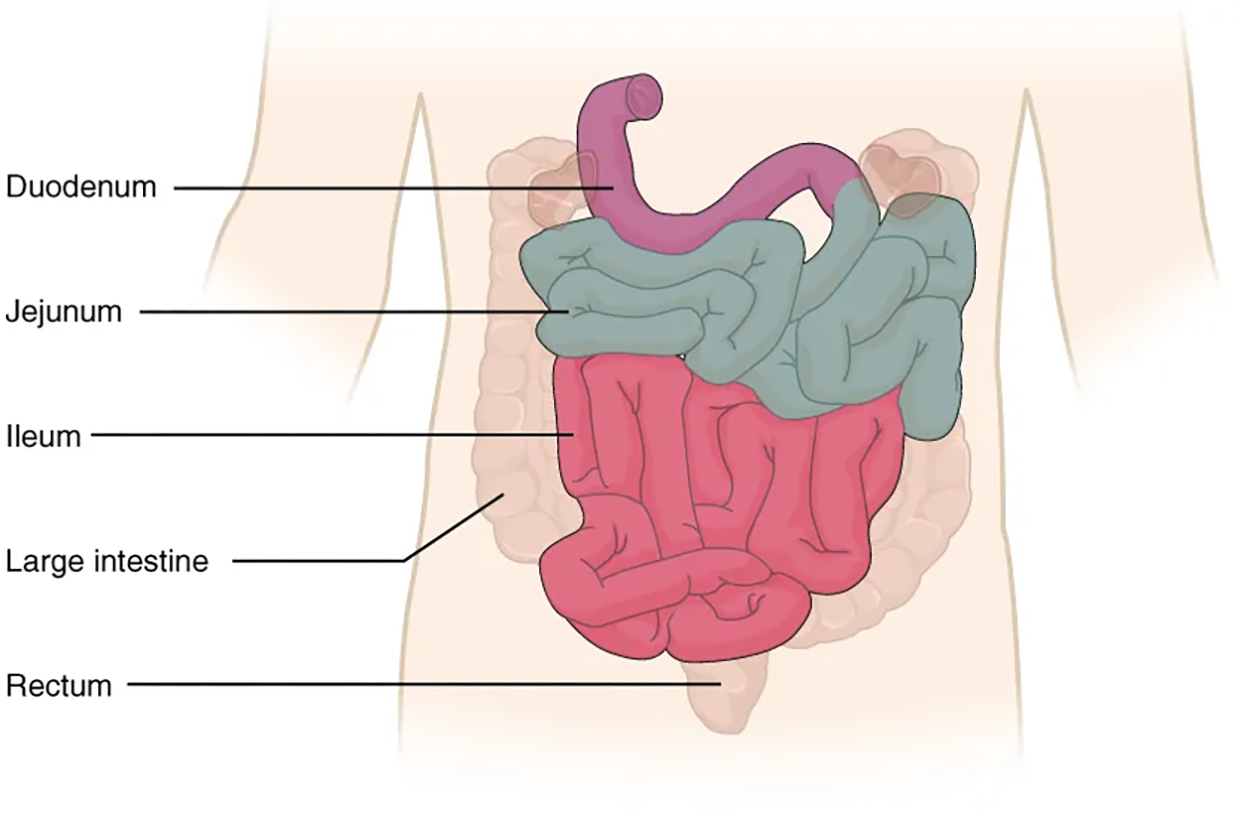

The coiled tube of the small intestine is subdivided into three regions. From proximal (at the stomach) to distal, these are the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum.

The shortest region is the 25.4-cm (10-in) duodenum, which begins at the pyloric sphincter. Just past the pyloric sphincter, it bends posteriorly behind the peritoneum, becoming retroperitoneal, and then makes a C-shaped curve around the head of the pancreas before ascending anteriorly again to return to the peritoneal cavity and join the jejunum. The duodenum can therefore be subdivided into four segments: the superior, descending, horizontal, and ascending duodenum.

Of particular interest is the hepatopancreatic ampulla (ampulla of Vater). Located in the duodenal wall, the ampulla marks the transition from the anterior portion of the alimentary canal to the mid-region and is where the bile duct (through which bile passes from the liver) and the main pancreatic duct (through which pancreatic juice passes from the pancreas) join. This ampulla opens into the duodenum at a tiny volcano-shaped structure called the major duodenal papilla. The hepatopancreatic sphincter (sphincter of Oddi) regulates the flow of both bile and pancreatic juice from the ampulla into the duodenum.

The jejunum is about 0.9 meters (3 feet) long (in life) and runs from the duodenum to the ileum. Jejunum means “empty” in Latin and supposedly was so named by the ancient Greeks who noticed it was always empty at death. No clear demarcation exists between the jejunum and the final segment of the small intestine, the ileum.

The ileum is the longest part of the small intestine, measuring about 1.8 meters (6 feet) in length. It is thicker, more vascular, and has more developed mucosal folds than the jejunum. The ileum joins the cecum, the first portion of the large intestine, at the ileocecal sphincter (or valve). The jejunum and ileum are tethered to the posterior abdominal wall by the mesentery. The large intestine frames these three parts of the small intestine.

Parasympathetic nerve fibers from the vagus nerve and sympathetic nerve fibers from the thoracic splanchnic nerve provide extrinsic innervation to the small intestine. The superior mesenteric artery is its main arterial supply. Veins run parallel to the arteries and drain into the superior mesenteric vein. Nutrient-rich blood from the small intestine is then carried to the liver via the hepatic portal vein.

| Term | Pronunciation | Audio File |

|---|---|---|

| Duodenum | du·o·de·num |

|

| Jejunum | je·ju·num |

|

| Ileum | il·e·um |

|

| Ileocecal Sphincter | Il·eo·ce·cal sphinc·ter |

|

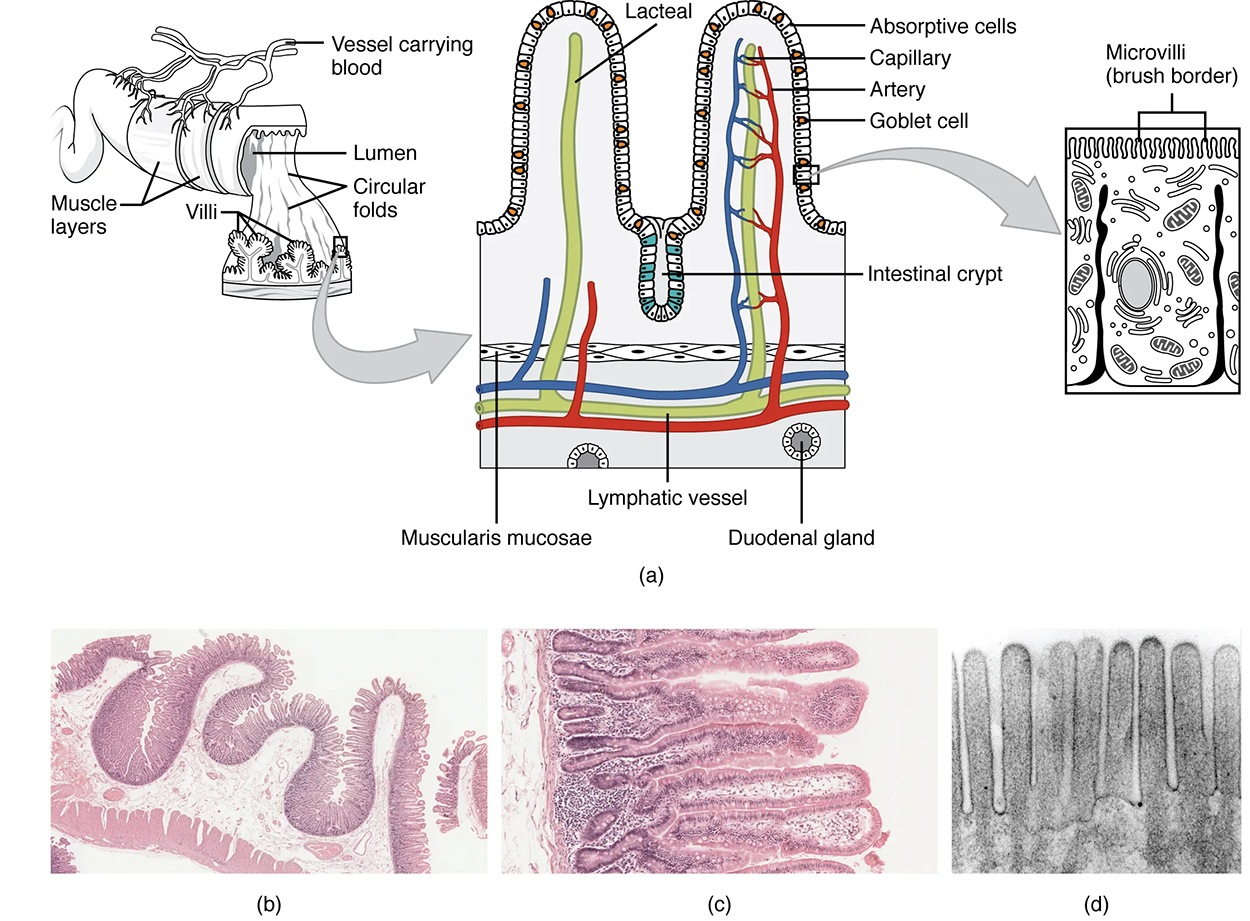

The wall of the small intestine is composed of the same four layers typically present in the alimentary system. However, three features of the mucosa and submucosa are unique. These features, which increase the absorptive surface area of the small intestine by more than 600-fold, include circular folds, villi, and microvilli. These adaptations are most abundant in the proximal two-thirds of the small intestine, where the majority of absorption occurs. Other features of the small intestine that aid in absorption and protecting the body include intestinal glands and intestinal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), respectively.

Also called a plica circulare, a circular fold is a deep ridge in the mucosa and submucosa. Beginning near the proximal part of the duodenum and ending near the middle of the ileum, these folds facilitate absorption. Their shape causes the chyme to spiral, rather than move in a straight line, through the small intestine. Spiraling slows the movement of chyme and provides the time needed for nutrients to be fully absorbed.

Within the circular folds are small (0.5–1 mm long) hairlike vascularized projections called villi (singular = villus) that give the mucosa a furry texture. There are about 20 to 40 villi per mm², increasing the surface area of the epithelium tremendously. The mucosal epithelium, primarily composed of absorptive cells, covers the villi. In addition to muscle and connective tissue to support its structure, each villus contains a capillary bed composed of one arteriole and one venule, as well as a lymphatic capillary called a lacteal. The breakdown products of carbohydrates and proteins (sugars and amino acids) can enter the bloodstream directly, but lipid breakdown products are absorbed by the lacteals and transported to the bloodstream via the lymphatic system.

As their name suggests, microvilli (singular = microvillus) are much smaller (1 µm) than villi. They are cylindrical apical surface extensions of the plasma membrane of the mucosa’s epithelial cells and are supported by microfilaments within those cells. Although their small size makes it difficult to see each microvillus, their combined microscopic appearance suggests a mass of bristles, which is termed the brush border. Fixed to the surface of the microvilli membranes are enzymes that finish digesting carbohydrates and proteins. There are an estimated 200 million microvilli per mm² of small intestine, greatly expanding the surface area of the plasma membrane and thus greatly enhancing absorption.

In addition to the three specialized absorptive features just discussed, the mucosa between the villi is dotted with deep crevices that each lead into a tubular intestinal gland (crypt of Lieberkühn), which is formed by cells that line the crevices (see the image above). These produce intestinal juice, a slightly alkaline (pH 7.4 to 7.8) mixture of water and mucus. Each day, about 0.95 to 1.9 liters (1 to 2 quarts) are secreted in response to the distention of the small intestine or the irritating effects of chyme on the intestinal mucosa.

In addition to the absorptive and goblet cells that are present in the intestinal glands, there are also paneth cells, which secrete bactericidal enzymes and can undergo phagocytosis, and enteroendocrine cells, which produce and release hormones in response to stimuli.

The submucosa of the duodenum is the only site of the complex mucus-secreting duodenal glands (Brunner’s glands), which produce a bicarbonate-rich alkaline mucus that buffers the acidic chyme as it enters from the stomach.

The lamina propria of the small intestine mucosa is studded with quite a bit of MALT. In addition to solitary lymphatic nodules, aggregations of intestinal MALT, which are typically referred to as Peyer’s patches, are concentrated in the distal ileum, and serve to keep bacteria from entering the bloodstream. Peyer’s patches are most prominent in young people and become less distinct as you age, which coincides with the general activity of our immune system.

| Term | Pronunciation | Audio File |

|---|---|---|

| Villi | vil·li |

|

| Lacteal | lac·te·al |

|

| Microvilli | mi·cro·vil·li |

|

| Duodenal Glands | du·o·de·nal g·lan·ds |

|

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX "ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E" ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/DETAILS/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL