Table of Contents |

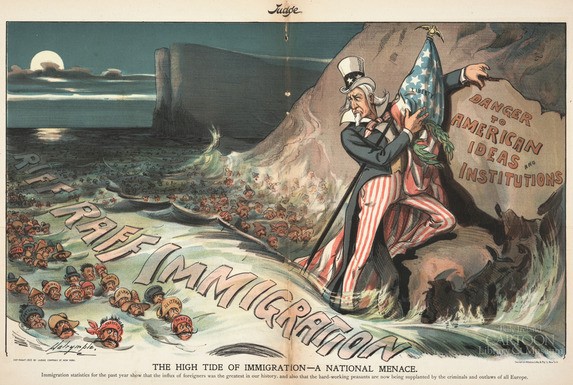

Historians have an astonishing array of tools at their disposal when they are engaging in the history-making process. They can use evidence from a number of sources including, but not limited to (a) oral interviews, (b) posters, (c) newspapers, (d) laws, (e) census data, (f) pictographs, (g) novels, (h) political cartoons, (i) maps, and (j) journals.

All of these represent examples of primary sources, or firsthand accounts/evidence from the time period that a historian is writing about or studying. Primary sources provide the foundation for any historical narrative.

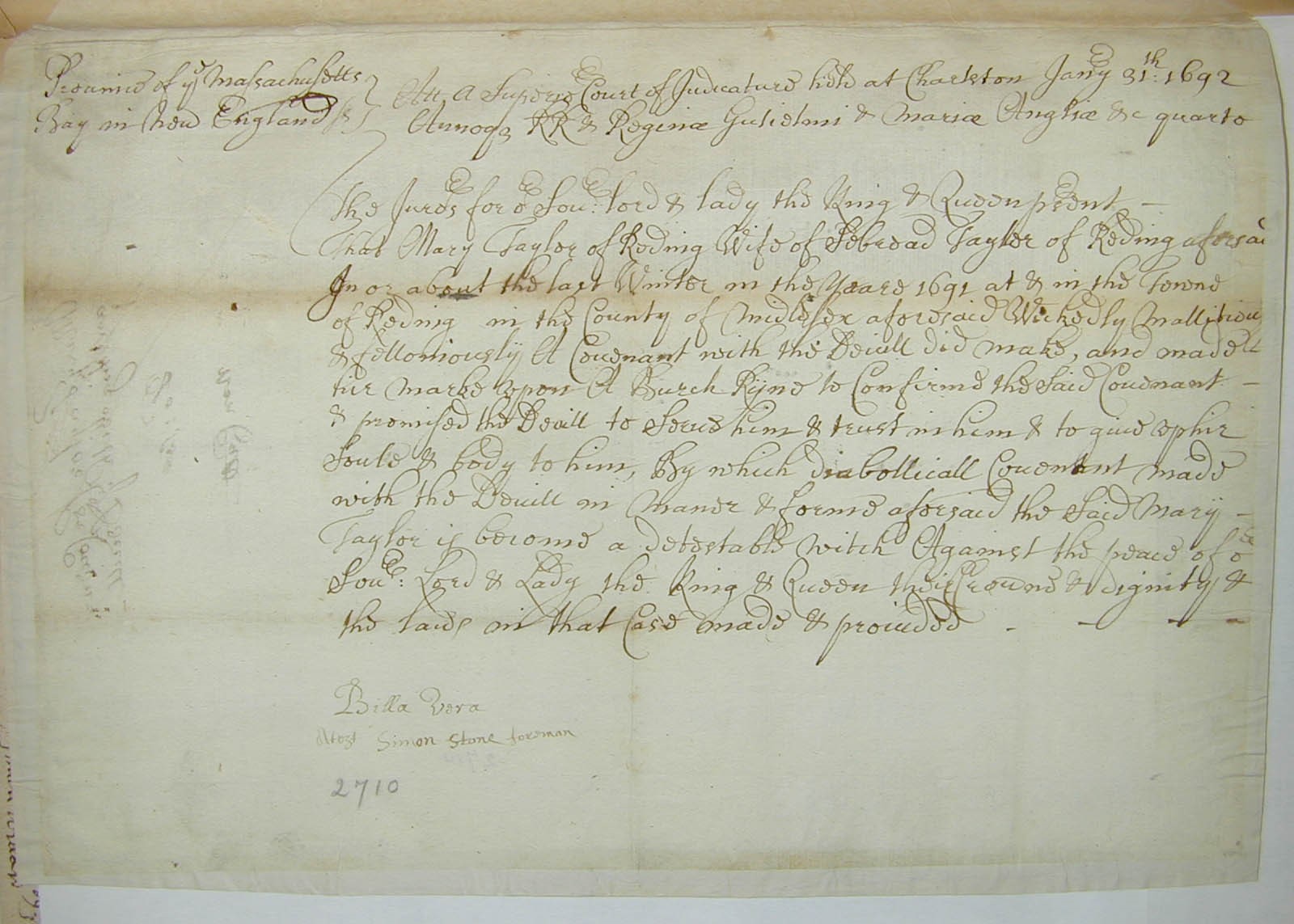

For example, we know that the Salem Witch Trials occurred in late-17th-century New England. We know this because a significant number of primary sources related to the event exist, including examinations of suspected witches, courtroom proceedings, and warrants for arrests.

If a historian wanted to investigate the Salem Witch Trials, they would find more primary sources similar to this one and create a story around these pieces of evidence. Historians can locate primary sources in a number of different places. Libraries and archives are an obvious choice, but historians can also find primary sources in local court buildings, federal offices, and historical societies. A number of primary sources are also becoming available on the internet.

Historians find and examine primary sources. Most importantly, they develop questions as they conduct research. For instance, why did town members accuse Taylor of making a “covenant with the devil"? What did such a phrase mean? Why was Mary Taylor singled out in the first place? These are just some of the questions a historian could develop while researching primary sources.

Unless a historian is studying an obscure event, the chances are high that someone has written about it. Thus, historians also refer to secondary sources or works by historians or other writers that contain interpretations of primary sources. Historians can develop their own interpretation of a historical event with assistance from secondary sources.

Secondary sources are the textbooks and history books that historians use to provide context for what they are writing about. They are used for learning more about the time period being studied, for fact-checking information it is written about, and as a jump-off point to expand the historical period in question. For example, a historian might read Emerson W. Baker's A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Witch Trials and the American Experience before writing their own history of people like Mary Taylor.

Remember that historians’ interpretations of past events change over time. A good rule of thumb is that the best secondary sources are the ones published most recently. Secondary sources can also include things like movies, documentaries, magazine articles, and websites; however, not all secondary sources are created equal. Historians generally rely on secondary sources that have been created by other historians.

One reason that historians take secondary source work seriously is that primary sources cannot always be taken at face value. Sometimes, there is evidence of bias in primary sources. Bias means: to have a particular perspective on something that is not objective or is without prejudice or persuasive intent. When an author creates a primary source, potential bias is created through the author’s (a) background, (b) personal beliefs, (c) intended audience, and (d) purpose for writing. In addition to potential bias, sometimes the source can be read in different contexts. At times, there lacks a clear path on how to use a primary source.

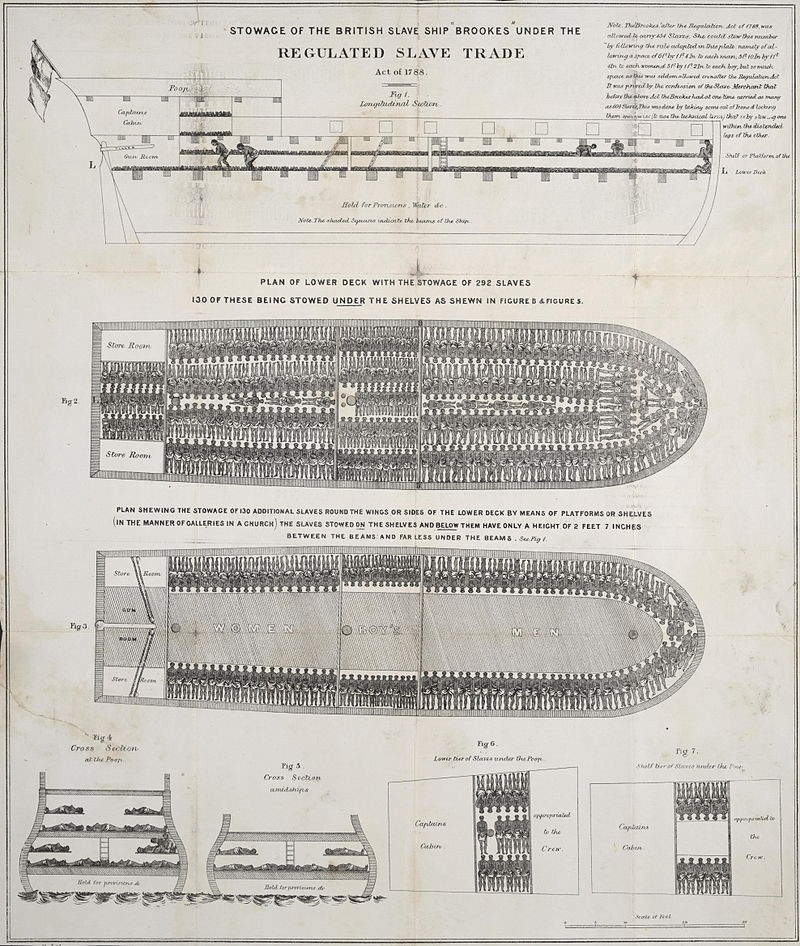

When put into the context of the trade of enslaved persons, we can see the ways that traders tried to maximize profit by putting African men, women, and children in cramped and confined conditions. The image shows over 450 people being crammed into small and confined spaces. But we also know, from other evidence like ship manifests, that ships like this often left the shores of Africa with up to 600 captured individuals on board. The image does not provide this information, but when used with other pieces of evidence (from primary or secondary sources), a more accurate story can be told.

When examined without a critical eye, this image depicts a tightly packed and inhumane means of transport that highlights the misery of the Middle Passage. But if you think about it critically or examine this primary source alongside other primary and secondary sources, a clearer picture emerges. On its own, this image underrepresents what actually occurred during the Atlantic slave trade. When combined with ship manifests, historians could derive estimates of how many Africans died while traveling the Middle Passage. Sometimes, information on how a primary source was used is also helpful. For instance, the image above was widely published as antislavery propaganda. Thus, when viewed critically rather than at face value, this image provided historians and the antislavery movement information about the trade of enslaved persons.

Primary sources can be tricky and are definitely better served when thought about both critically and historically. There are a variety of ways in which historians think about primary sources. The perspective might change depending on whom you ask. There is, however, a straightforward and easy-to-remember way to approach primary sources.

During your early school years, you were probably asked to remember these six questions: who, what, when, where, why, and how. These are excellent starter questions to approach every primary source with. Whenever you come across a primary source, ask yourself:

By applying these questions to primary and secondary sources, you will begin to think like a historian. Primary sources can be complex, so you should use historical and critical thinking skills when examining them. Critical thinking is a tricky concept to define, but it fundamentally means creating a clear, self-directed, and evidence-based judgment on a topic. In other words, when creating stories about the past the historian needs to take a responsible approach, judge the evidence at hand, and create a story with the information.

One way that historians do this is by thinking historically about an event and its related primary sources. This can be accomplished through a variety of intellectual channels, but an easy one to remember is to think in terms of the five Cs, seen in the following list (Andrews & Burke, 2007).

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL

REFERENCES

Andrews, T., & Burke, F. (2007, January). What does it mean to think historically? Retrieved October 26, 2016, from www.historians.org/research-and-publications/perspectives-on-history/january-2007/what-does-it-mean-to-think-historically