Table of Contents |

Epidemiology is a field of study that examines the geographical distribution of disease, patterns and timing of the number of individuals affected by disease, and disease control and transmission. When medical professionals encounter patients with unusual symptoms or a concerning pattern of increased numbers of cases of a disease, they can notify epidemiologists. This allows epidemiologists to identify the disease and whether it is new or known. Additionally, it allows epidemiologists to recognize if a new disease is becoming more common so that they can examine the reason for the increase and find ways to prevent it from spreading.

Some epidemiologists work for large organizations that serve as repositories of information about communicable diseases and provide recommendations and guidelines to help prevent transmission. You will learn more about some of these organizations and their roles in the lesson on public health.

Epidemiology has an extensive and fascinating history that goes beyond the scope of this course, but it is important to understand some major milestones and how they contributed to modern epidemiology.

Epidemiology has existed in an informal form for as long as physicians have treated disease and paid attention to patterns with the aim of reducing disease transmission. Many of the topics covered in the lesson on the history of microbiology directly or indirectly relate to the history of epidemiology as they illustrate how people began to learn more about the causes of disease and how diseases are transmitted. The transition to widespread acceptance of the germ theory of disease in the 19th century laid the groundwork for major progress in epidemiology.

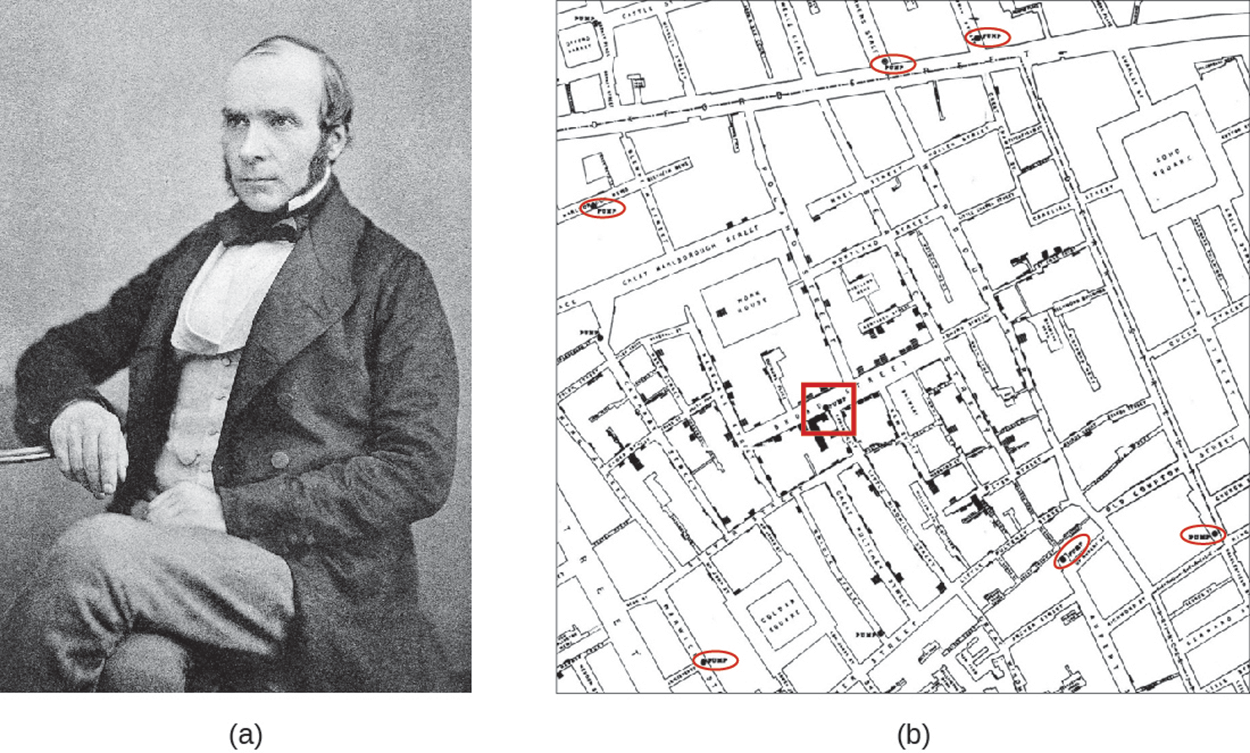

One of the most famous examples of epidemiology involves the work of British physician John Snow (1813–1858), sometimes called the father of epidemiology for his pioneering work. Snow had made observations during a cholera outbreak (a sudden, localized increase in cases of a disease above expected levels; WHO, 2022) that occurred from 1848 to 1849 that led him to believe that cholera was spread through fecal-oral transmission. In other words, he believed that microbes in feces that were accidentally ingested (e.g., through contaminated food or water) led to the development of cholera.

IN CONTEXT

When another cholera epidemic occurred in London (the 1854 Broad Street cholera epidemic), Snow was prepared to investigate. An epidemic is an event in which the number of cases becomes greater than expected during a short time within a geographic region. Because Snow thought that cholera might spread through contaminated water, he searched for this source. He found that there was a high frequency of cholera cases among people who obtained their water from the River Thames downstream from London, which contained refuse and sewage from people upstream. He also made a related observation that brewery workers who preferred to drink beer over water did not contract cholera. Additionally, he carefully mapped the incidence of cholera and found a high frequency of cases among individuals who used a particular water pump located on Broad Street. Based on Snow’s recommendation, local officials removed the pump’s handle and this had a dramatic effect in reducing cases of cholera. This represented the first known public health response to an epidemic. Modern epidemiologists use similar methods to identify cases of disease and identify how the disease is spread so that they can develop ways to control it.

The image below shows a photo of John Snow in part (a) and Snow’s detailed map of cholera incidence that identified the Broad Street water pump in part (b). The water pump itself is enclosed in a red square.

Other examples of pioneers in the field of epidemiology are British nurse Florence Nightingale (1820–1910; Selanders, 2020) and British surgeon Joseph Lister (1827–1912). Florence Nightingale was a nurse dispatched by the British military to care for wounded soldiers during the Crimean War. She kept meticulous data on illness and death, which allowed her to identify that infectious diseases that she considered preventable were responsible for more deaths than injuries sustained during fighting. Lister documented that the use of disinfection protocols reduced the risk of infections after surgery. More information about Lister and additional examples are included in the lesson on the germ theory of disease.

By studying patterns of disease occurrence and transmission, epidemiologists can identify distinct patterns of spread. This is important in determining the best ways to control a disease.

The cholera epidemic studied by Snow was an example of a common source spread of infectious disease, meaning that people were exposed to a specific source (the Broad Street pump). Another example of common source spread occurred when many people developed Legionnaires' disease following an American Legion convention in Philadelphia in 1976. By gathering information from patients, researchers were able to find that a common link was that they attended the convention (Winn, 1988).

There are multiple patterns of common course spread. In continuous common source spread, the infection occurs for an extended time (longer than the incubation period). This could occur if a contaminated source (like the London water pump) continues to expose people for an extended time. In intermittent common source spread, infections occur for a period, stop, and then increase again. For example, flooding that causes runoff to contaminate a water supply might cause disease temporarily that then stops until flooding occurs again.

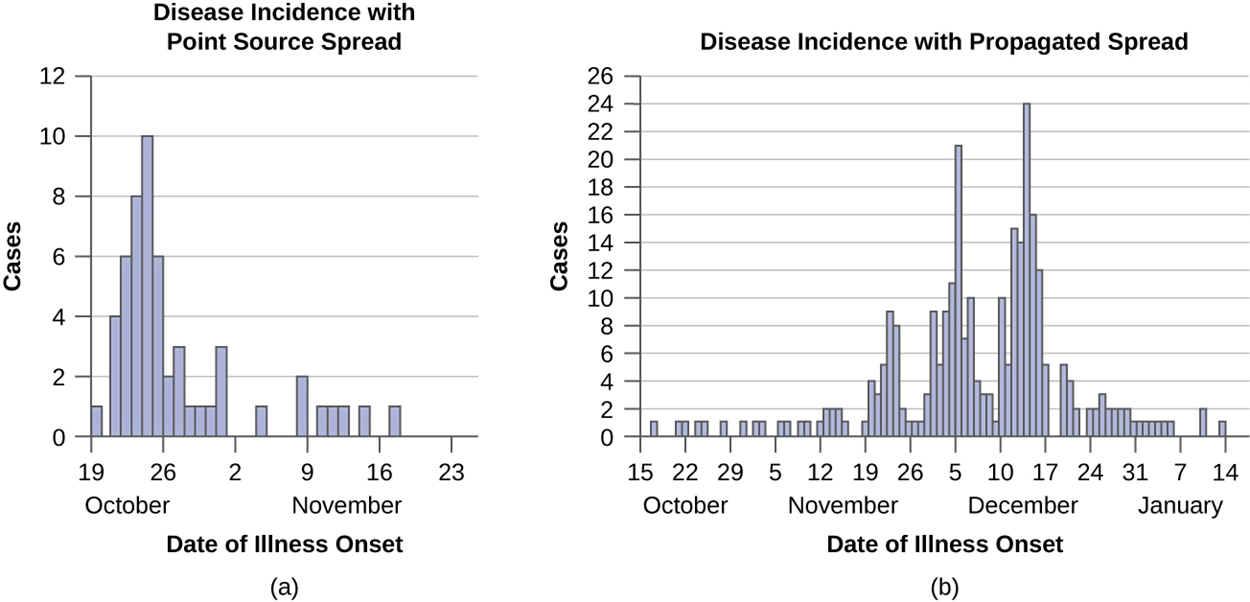

Other methods of disease spread show different patterns. For example, point source spread occurs when there is a common source that contains the pathogen but only operates for a very short time (less than the incubation period). For example, a contaminated batch of potato salad at a picnic may cause a sudden increase in cases of food poisoning.

Propagated spread occurs through direct or indirect contact between people rather than from a common source such as a well. There is no single source of infection. Unless the spread of the disease is stopped immediately, it spreads for longer than the incubation period. This type of spread typically lasts longer and can vary in duration. It is often more difficult to contain than a disease caused by a single contaminated source that can be closed, disinfected, removed, or otherwise prevented from transmitting pathogens. Influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, are examples of viruses that are spread in this manner.

The image below shows how different patterns of disease spread can be identified by examining patterns in graphs. Graph (a) shows how a disease with point source spread shows a sudden peak of cases that rapidly drops off. In contrast, graph (b) shows how a disease with propagated spread increases as more and more people are infected and spread the disease to others.

Modern epidemiology relies on two major types of studies: observational studies and experimental studies. Observational studies involve collecting data about individuals who have not been subjected to an experimental treatment. Experimental studies involve manipulation of study subjects. One way of manipulating study subjects is by randomly assigning them into groups similar in size when possible. Then, one group is given the treatment and the other is not.

In observational studies, researchers collect data (such as measurements of white blood cell counts or survey data) from people who have not been subjected to an experimental treatment. Subjects are often chosen at random to obtain a representative sample of people in general.

EXAMPLE

A researcher may randomly select and compare groups of people who were diagnosed with a disease with a group of people who did not have the disease so that they can see how these individuals differ. This could allow the researchers to examine a variety of hypotheses. For example, they could look at risk factors associated with infection or look for ways in which the infection may have affected people.Observational studies can measure associations between disease occurrence and possible causative agents but do not necessarily prove a causal relationship. There may be some sort of correlation involved.

EXAMPLE

Perhaps a disease originated from a pathogen emitted from a contaminated air conditioner at a coffee bar, but the observational study relies on a survey that notes that people who drink coffee are more likely to develop the disease.The table below summarizes types of observational studies.

| Type of Study | Description |

|---|---|

| Descriptive epidemiology | Gathers data about a disease such as the number of affected individuals, how the disease spreads, etc. |

| Analytical epidemiology | Collects data from carefully selected groups of individuals (generally selected at random from within larger groups) to evaluate hypotheses |

| Prospective study | A study that evaluates individuals going forward in time (e.g., by following the progress of individuals diagnosed with a disease); may be observational or experimental |

| Retrospective study | A study that gathers data from the past, such as medical records data, to analyze patterns; for example, a researcher might compare vaccination records of individuals who receive a diagnosis of a disease |

| Cohort study | A study that examines a group of individuals (i.e., a cohort) that shares a common characteristic (e.g., individuals born in the same year, smokers versus nonsmokers) |

| Case-control study | A study (typically retrospective) that compares groups of individuals with and without a condition |

| Cross-sectional study | A study that analyzes randomly selected individuals in a population and compares them (e.g., comparing individuals affected versus unaffected by a disease to look for similarities and differences); also used to examine disease prevalence (the number or proportion of individuals with a given condition or disease at a particular time) |

Experimental studies involve manipulation of study subjects in some way. They can be conducted in the laboratory or can be clinical studies.

EXAMPLE

Researchers might randomly assign people to receive a treatment or a placebo (something that simulates a treatment, such as a sugar pill) to compare how quickly they recover from an illness. A placebo is often used so that people don’t know whether they are receiving the medication. In a double-blind study, neither the researchers nor the participants know who has received the treatment and this helps to eliminate subjective interpretations (e.g., the placebo effect, in which participants respond to treatment better because they think the medication will help rather than because of the actual effects of the medication).Experimental studies provide the strongest evidence for treatments and for relationships between causative agents and disease, but they are sometimes not feasible or ethical.

EXAMPLE

It would not be ethical to expose a group of people to a dangerous disease.Epidemiological studies are carried out with reference to a population, which is the group of individuals that are at risk of the disease or condition. The population can be defined in a variety of ways depending on the interests of the researcher.

EXAMPLE

A population might include all susceptible individuals within a geographic region or might include a subset of individuals at particular risk (such as people living in close proximity, like college students in dormitories). Being able to define a population is important because most measures of interest in epidemiology are made with reference to the size of the population.For epidemiological analyses, certain terms are often used. These are summarized below.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Morbidity | The state of being diseased. |

| Total morbidity (morbidity) | The number of diseased individuals (not expressed as a percentage of the population). |

| Morbidity rate | The number of diseased individuals expressed as a percentage of the population or out of a standard number of individuals in the population (such as 100,000). |

| Mortality | Death |

| Mortality rate | The percentage of a population that has died from a disease out of the total population or out of a standard number (e.g., number of deaths out of 100,000 individuals). |

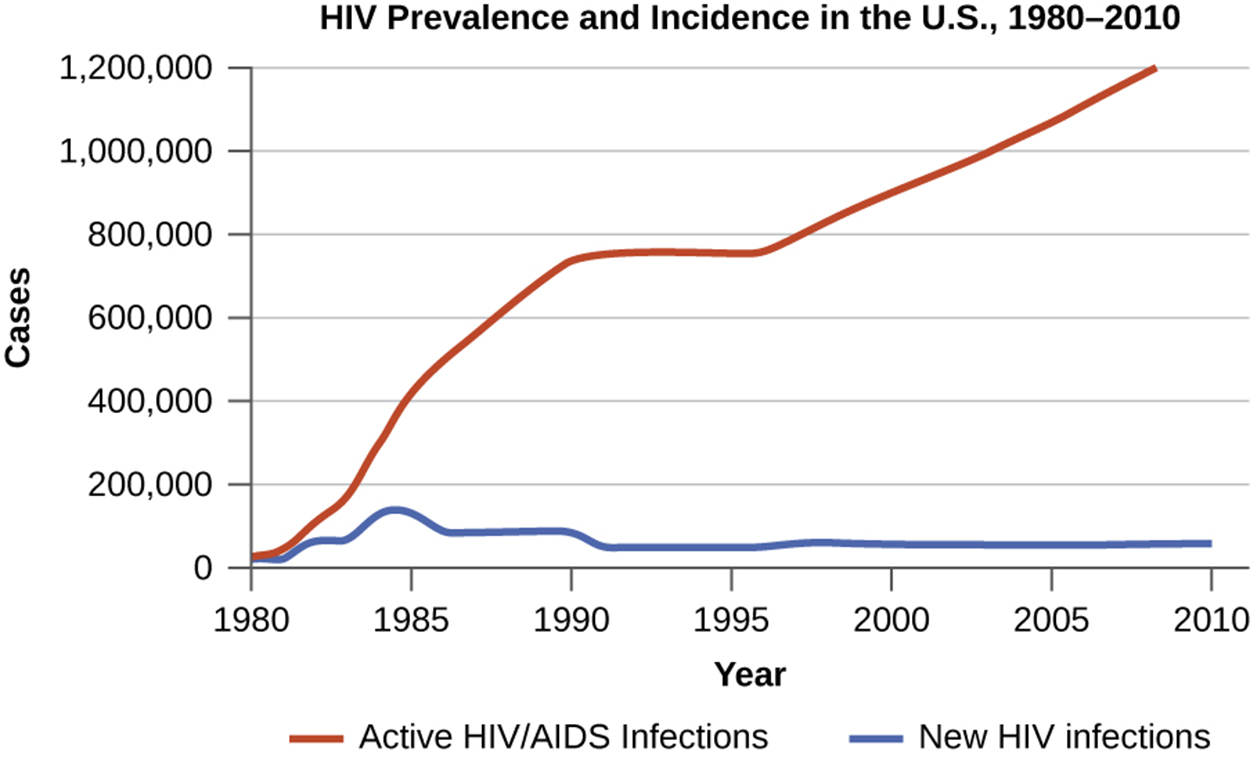

| Prevalence | The number, or proportion, of individuals in a given population who have a disease at a particular time. |

| Incidence | The number or proportion of new cases within a particular time. |

"Total morbidity" is sometimes simply called "morbidity". However, the term “total morbidity” is used in a more specific sense, and it refers to the number of diseased individuals. In contrast, “morbidity” simply refers to the state of being diseased. Another point to note is that it is possible to calculate the prevalence and incidence for mortality, not just for morbidity.

The graph below shows the prevalence and incidence of HIV in the United States from 1980 to 2010. Note that the number of active infections increases because people can develop the illness and survive (especially with appropriate treatment). This increases the number of infected individuals in the population over time. However, the number of new cases remains relatively steady from the early 1990s through 2010.

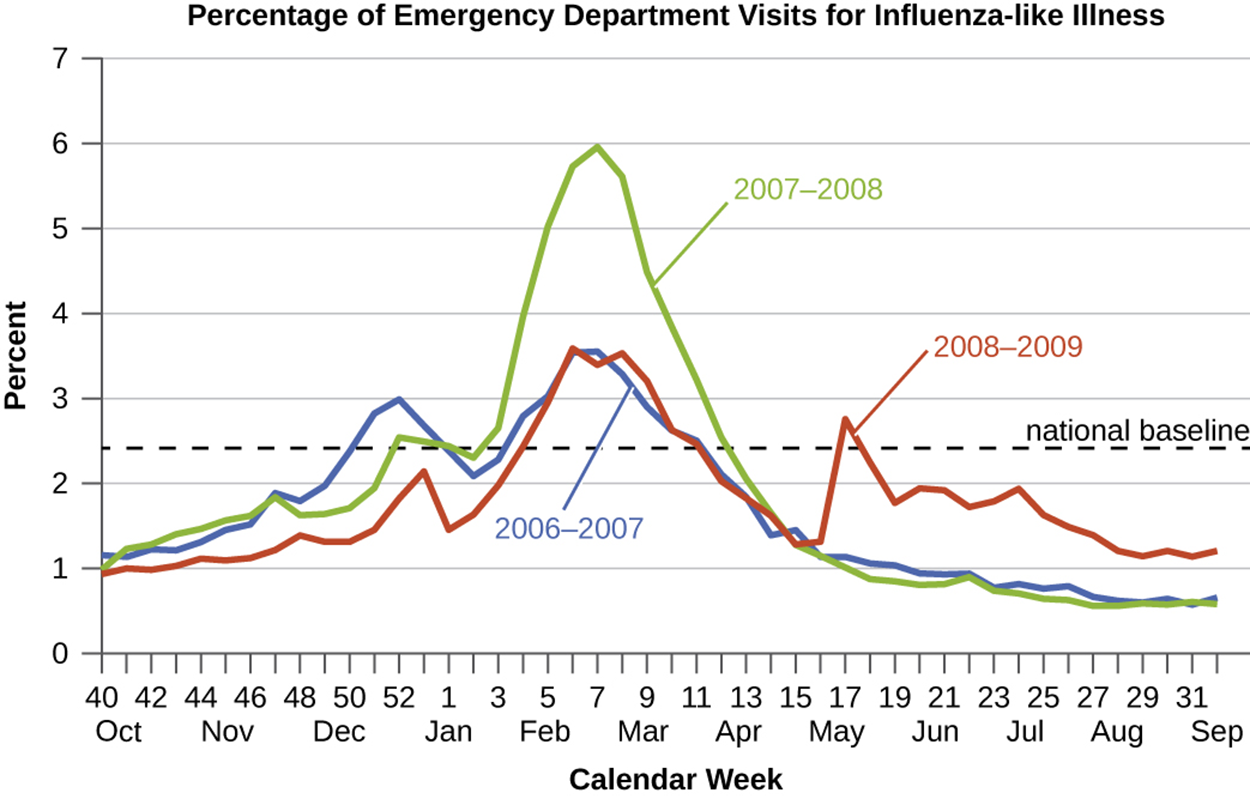

Diseases can be described by their patterns of incidence. These terms help to convey the severity of the risk of spread of the disease. For example, sporadic diseases occur occasionally, usually without any particular geographic concentration. In contrast, endemic diseases are constantly present (often at a low level) in a population in a particular geographic region.

When the number of cases of diseases increases more than expected within a short time within a particular geographic region, the disease is described as an epidemic. The graph below shows the percentage of emergency department visits for influenza-like illnesses for several years compared with a national baseline. Seasonal increases are considered normal rather than examples of epidemics. However, unusually large increases meet the criteria for being considered epidemics.

Epidemics generally occur because of some sort of change, such as a change in environmental conditions, in the population, or in the pathogen itself. Influenza strains change from year to year and greater changes in the strains increase the risk of the virus evading the immune system and therefore it is common to see increases in cases.

In some cases, increases in the number of cases occur on a very large or worldwide scale. When an epidemic occurs at this level, it is called a pandemic. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus is a recent example.

One component of epidemiology involves determining the etiology (cause) of a disease. A pathogen that produces a particular disease is called the etiologic agent or causative agent of that disease.

It can be challenging to determine that a particular pathogen is definitely the causative agent of a particular disease. As you learned in the lessons on germ theory of disease and Koch's postulates, Koch’s postulates and molecular Koch’s postulates can be used, but have limitations.

When an outbreak (sudden appearance of cases) of a disease occurs, it can be difficult to determine which pathogen is responsible. Many symptoms, such as gastrointestinal pain or fever, are nonspecific (meaning that they don’t clearly indicate one particular illness). It can be possible to find associations between pathogens and disease. Epidemiologists commonly look for commonalities between infected individuals to help determine the source of the disease. However, definitive determination of the causative agent requires using molecular Koch’s postulates or, when appropriate and ethical, controlled experiments.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “MICROBIOLOGY.” ACCESS FOR FREE AT openstax.org/details/books/microbiology. LICENSE: CC ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

Selanders, L. (2022, October 23). Florence Nightingale. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved December 7, 2022, from www.britannica.com/biography/Florence-Nightingale

World Health Organization (WHO). (2022). Disease outbreaks. Retrieved December 7, 2022, from www.who.int/teams/environment-climate-change-and-health/emergencies/disease-outbreaks

Winn W. C., Jr (1988). Legionnaires disease: historical perspective. Clinical microbiology reviews, 1(1), 60–81. doi.org/10.1128/CMR.1.1.60