Table of Contents |

The adrenal glands are wedges of glandular and neuroendocrine tissue adhering to the top of the kidneys by a fibrous capsule. The adrenal glands have a rich blood supply and experience one of the highest rates of blood flow in the body. They are served by several arteries branching off the aorta, including the suprarenal and renal arteries. Blood flows to each adrenal gland at the adrenal cortex and then drains into the adrenal medulla. Adrenal hormones are released into the circulation via the left and right suprarenal veins.

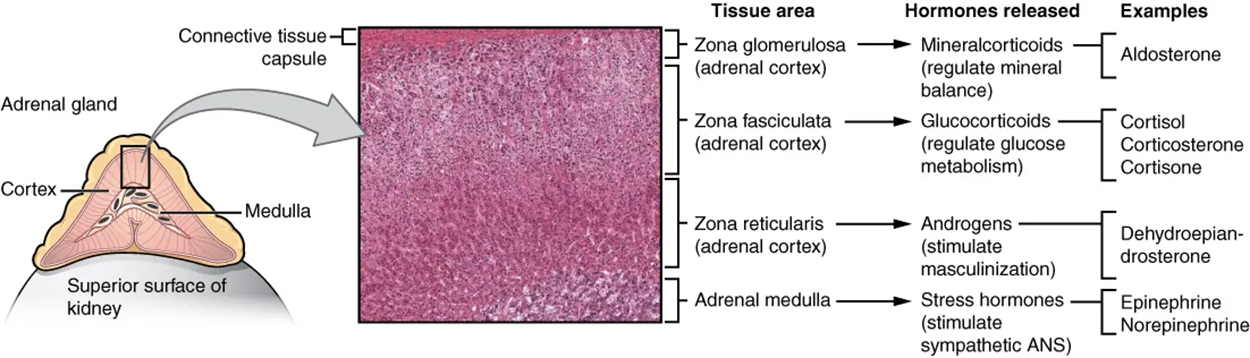

The adrenal gland consists of an outer cortex of glandular tissue and an inner medulla of nervous tissue. The cortex itself is divided into three zones:

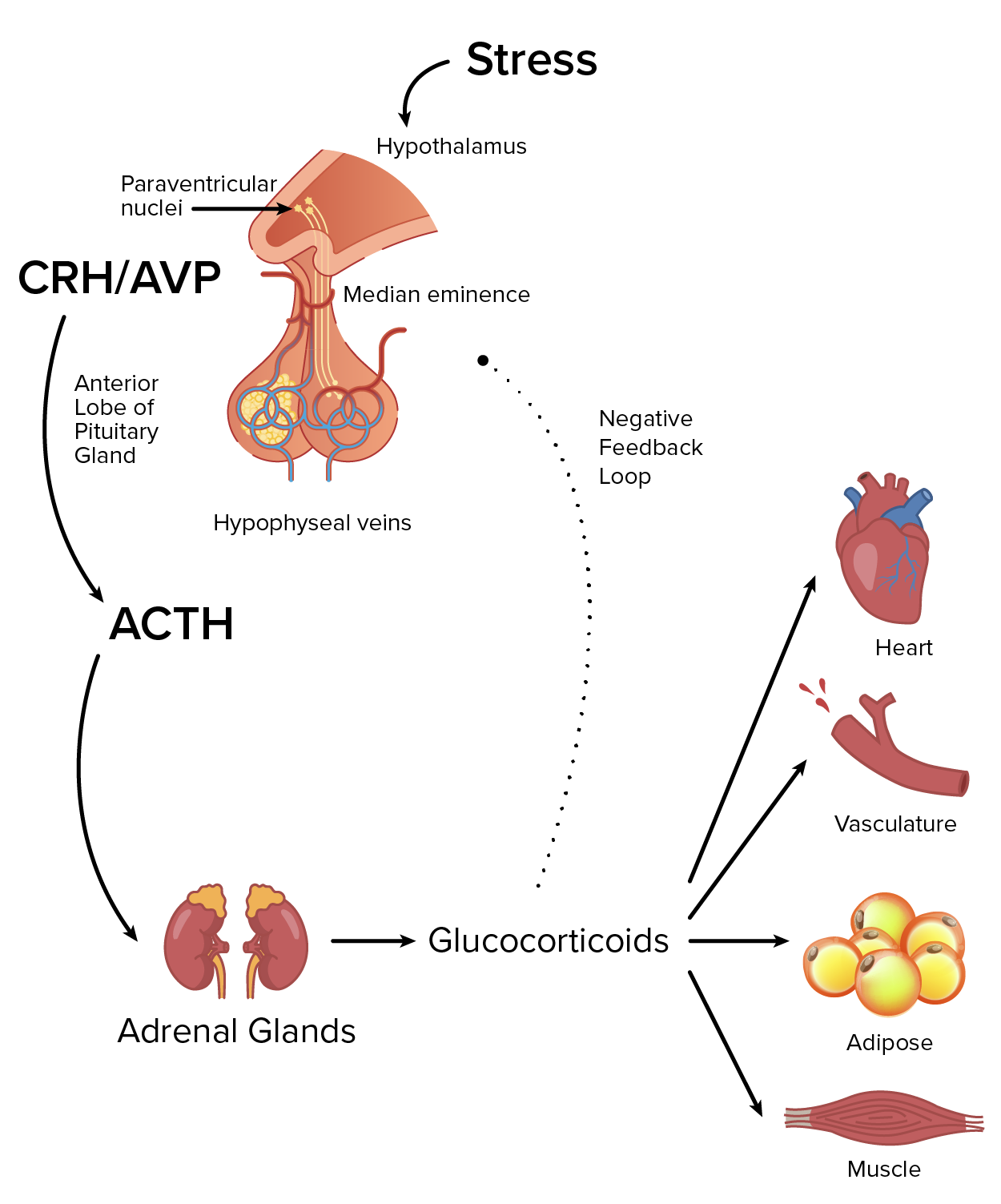

The adrenal cortex, as a component of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, secretes steroid hormones important for the regulation of the long-term stress response, blood pressure and volume, nutrient uptake and storage, fluid and electrolyte balance, and inflammation. The HPA axis involves the stimulation of hormone release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary by the hypothalamus. ACTH then stimulates the adrenal cortex to produce the hormone cortisol. This pathway will be discussed in more detail below.

The adrenal medulla is neuroendocrine tissue composed of postganglionic sympathetic nervous system (SNS) neurons. It is really an extension of the autonomic nervous system, which regulates homeostasis in the body. The sympathomedullary (SAM) pathway involves the stimulation of the medulla by impulses from the hypothalamus via neurons from the thoracic spinal cord. The medulla is stimulated to secrete the amine hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine.

IN CONTEXT

General Adaptation Syndrome

The body responds in different ways to short-term stress and long-term stress following a pattern known as the general adaptation syndrome (GAS).

Stage one of GAS is called the alarm reaction. This is short-term stress, the fight-or-flight response, mediated by the hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine from the adrenal medulla via the SAM pathway. Their function is to prepare the body for extreme physical exertion. Once this stress is relieved, the body quickly returns to normal. The section on the adrenal medulla covers this response in more detail.

EXAMPLE

Have you ever experienced what feels like butterflies in your stomach, excessive sweating, or trembling hands when you were getting ready to take a test? This is an example of your body reacting to the stress of taking a test by the alarm reaction.

If the stress is not soon relieved, the body adapts to the stress in the second stage called the stage of resistance. If a person is starving, for example, the body may send signals to the gastrointestinal tract to maximize the absorption of nutrients from food.

EXAMPLE

If you finished your test but don’t feel quite back to normal yet, and you can't focus on anything else yet, this may be your body undergoing the stage of resistance.

However, if the stress continues for a longer amount of time, the body responds with symptoms quite different than the fight-or-flight response. During the third stage, the stage of exhaustion, individuals may begin to suffer depression, the suppression of their immune response, severe fatigue, or even a fatal heart attack. These symptoms are mediated by the hormones of the adrenal cortex, especially cortisol, released as a result of signals from the HPA axis.

EXAMPLE

If you got home after completing your test and felt exhausted, depressed, and anxious, this may be your body exhibiting the stage of exhaustion.

Adrenal hormones also have several non-stress-related functions, including the increase of blood sodium and glucose levels, which will be described in detail below.

The adrenal cortex consists of multiple layers of lipid-storing cells that occur in three structurally distinct regions. Each of these regions produces different hormones.

The most superficial region of the adrenal cortex is the zona glomerulosa, which produces a group of hormones collectively referred to as mineralocorticoids because of their effect on body minerals, especially sodium and potassium. These hormones are essential for fluid and electrolyte balance.

Aldosterone is the major mineralocorticoid. It is important in the regulation of the concentration of sodium and potassium ions in urine, sweat, and saliva. For example, it is released in response to elevated blood K⁺, low blood Na⁺, low blood pressure, or low blood volume. In response, aldosterone increases the excretion of K⁺ and the retention of Na⁺, which in turn increases blood volume and blood pressure. Its secretion is prompted when corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus triggers ACTH release from the anterior pituitary.

Aldosterone is also a key component of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), in which specialized cells of the kidneys secrete the enzyme renin in response to low blood volume or low blood pressure. Renin then catalyzes the conversion of the blood protein angiotensinogen, produced by the liver, to the hormone angiotensin I. Angiotensin I is converted in the lungs to angiotensin II by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE).

Angiotensin II has three major functions:

The intermediate region of the adrenal cortex is the zona fasciculata, named as such because the cells form small fascicles (bundles) separated by tiny blood vessels. The cells of the zona fasciculata produce hormones called glucocorticoids because of their role in glucose metabolism. The most important of these is cortisol, some of which the liver converts to cortisone. A glucocorticoid produced in much smaller amounts is corticosterone.

In response to long-term stressors, the HPA axis is stimulated and results in the release of glucocorticoids. The image below depicts this negative feedback loop. When an individual is exposed to a stress stimulus, the hypophysiotropic neurons in the paraventricular nuclei (PVN) of the hypothalamus secrete CRH and arginine vasopressin (AVP). Upon reaching the anterior pituitary, CRH binds to corticotropin receptor factor (CRF) type 1 receptors. ACTH is then released and binds to its receptors in the zona fasciculata. This causes the release of glucocorticoids, including cortisol.

The overall effect of glucocorticoids is inhibiting tissue building while stimulating the breakdown of stored nutrients to maintain adequate fuel supplies, and they affect numerous parts of the body, including the heart, vasculature, adipose tissue, and muscle tissue. In conditions of long-term stress, for example, cortisol promotes the catabolism of glycogen to glucose, the catabolism of stored triglycerides into fatty acids and glycerol, and the catabolism of muscle proteins into amino acids. These raw materials can then be used to synthesize additional glucose and ketones for use as body fuels. The hippocampus, which is part of the temporal lobe of the cerebral cortices and important in memory formation, is highly sensitive to stress levels because of its many glucocorticoid receptors.

The deepest region of the adrenal cortex is the zona reticularis, which produces small amounts of a class of steroid sex hormones called androgens. During puberty and most of adulthood, androgens are produced in the gonads. The androgens produced in the zona reticularis supplement the gonadal androgens. They are produced in response to ACTH from the anterior pituitary and are converted in the tissues to testosterone or estrogens.

In adult females, androgens may contribute to sex drive, but their function in adult males is not well understood. In post-menopausal people, as the functions of the ovaries decline, the main source of estrogens becomes the androgens produced by the zona reticularis.

As noted earlier, the adrenal cortex releases glucocorticoids in response to long-term stress such as severe illness. In contrast, the adrenal medulla releases its hormones in response to acute, short-term stress mediated by the SNS.

The medullary tissue is composed of unique postganglionic SNS neurons called chromaffin cells, which are large and irregularly shaped, and produce the neurotransmitters epinephrine (also called adrenaline) and norepinephrine (or noradrenaline).

Epinephrine is produced in greater quantities—approximately a 4 to 1 ratio with norepinephrine—and is the more powerful hormone. Because the chromaffin cells release epinephrine and norepinephrine into the systemic circulation, where they travel widely and exert effects on distant cells, they are considered hormones. Derived from the amino acid tyrosine, they are chemically classified as catecholamines.

The major hormones of the adrenal glands are summarized in the table below.

| Major Hormones of the Adrenal Glands | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adrenal gland | Associated hormones | Chemical class | Hormone group | Effect |

| Adrenal cortex | Aldosterone | Steroid | Mineralocorticoid | Increases blood Na⁺ levels |

| Adrenal cortex | Cortisol, corticosterone, cortisone | Steroid | Glucocorticoid | Increases blood glucose levels |

| Adrenal medulla | Epinephrine, norepinephrine | Amine | Catecholamine | Stimulates fight-or-flight response |

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.