Table of Contents |

Discovering knowledgeability, or the state or condition of possessing knowledge, involves careful assessment of the audience by the speaker prior to, during, and after the speech. The speaker wants to think about and contemplate the world of the audience to understand what they know.

Knowledge is familiarity with someone or something, which can include facts, information, descriptions, or skills acquired through experience or education. It can refer to the theoretical or practical understanding of a subject.

Knowledge can be implicit (as with practical skill or expertise) or explicit (as with the theoretical knowledge of a subject); it can also be more or less formal or systematic. In this case, knowledgeability is the condition or state of knowing by the members of the audience. The audience may know more about one topic and less about another. The types of knowledge are also different—the audience may know about something but not know how to use the knowledge to actually do something.

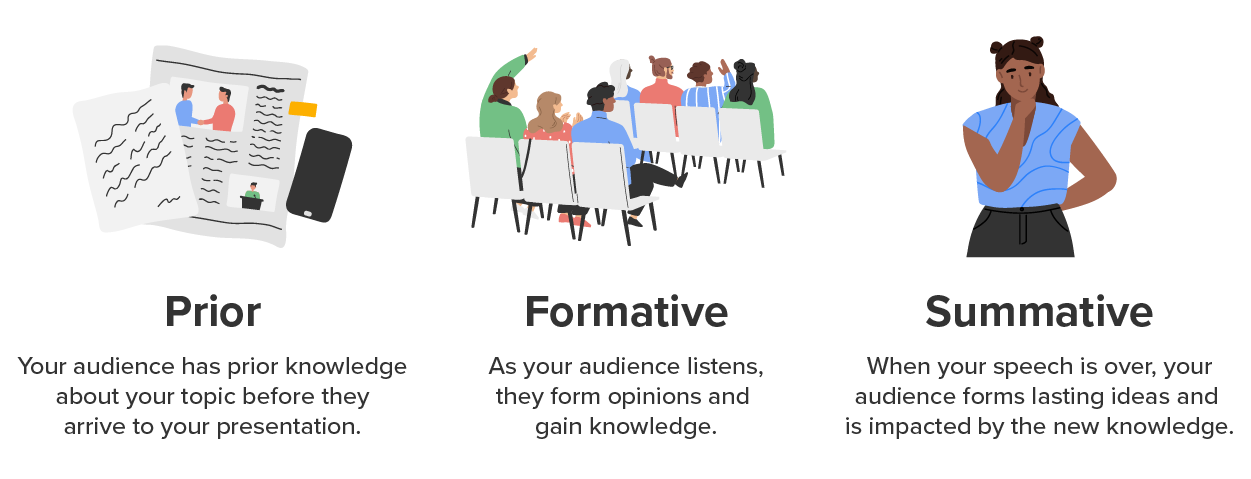

There are at least three types of knowledgeability: prior, formative, and summative. To distinguish the three, one might think about a cook. A cook gathers the ingredients (prior), tastes the soup while it is cooking (formative), and lets the diner judge it at the end (summative).

Let's consider these types of knowledge to determine how effective your speech will be.

Prior knowledge is the knowledge that the audience already has about your topic. If your idea or concept is unfamiliar to the audience, you may assume that they know nothing and start from the very beginning.

However, you may want to "pre-assess" your audience to see how much they know so that you can adjust your content to the level of understanding. Where do you start your explanation? How much does your audience already know about your topic? You don't want to explain things that everyone already knows about and bore most of the audience, yet at the same time, you want to make sure that everyone does understand your ideas.

You want the audience members to leave with an understanding which was greater than when they walked into the room or turned on their computers to listen to your speech.

Formative knowledge is the knowledge forming in the audience's mind during the speech. It is what the audience is learning (or not learning) during your speech.

You may assess understanding with a simple question-and-answer session, or you may find it useful to use an audience response system at different points in the speech to ask the audience short, quick questions to see where they are at that point.

If you see confused looks on the faces of audience members or turning to neighbors with questions, you know that you need to try again to explain what you were saying in different words or with better supporting examples.

Summative knowledge is the knowledge that the audience leaves with after your speech.

What is the level of understanding at the end of your speech? Do they know more, or can they do something which they could not do before the speech?

Again, you may ask the audience to complete a short questionnaire at the end or use an audience response system with automatic result tabulation to see how the audience has changed.

We’ve covered all of the information you need about your audience—so how do you go about collecting these crucial facts that will help shape your speech? There are several useful methods to consider, including:

Direct observation allows you to get to know the members of your audience personally. You are making observations of audience members through your own senses, such as hearing, sight, and perhaps smell.

You can employ this method in a classroom or small group situation through conversations with others and by listening to what they say.

However, you will want to guard against introducing your own egocentric biases into the observation. Our human senses do not function like a video camcorder, impartially recording all observations.

Thus, two people can view the same audience and come away with entirely different perceptions of it, even disagreeing about simple facts. This is why eyewitness testimony is notoriously unreliable.

An interview is a conversation between two people—the interviewer and the interviewee—that involves asking questions to obtain information. For large audiences, you could use computer-assisted web interviewing (CAWI).

When interviewing, remember to allow the interviewee time to respond to your question without interrupting. Also, leave a few brief pauses between one question and the next so the interviewee can supply additional information.

Or, probe before moving on to the next question. Usually, you want to prepare a list of questions in advance and move from more general to specific questions.

Generally, you will be using the following four different types of questions.

Four Types of Questions for Interviews

| Question Type | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Open-Ended | Questions that ask who, what, where, when, why, and how are generally good open-ended questions. An open-ended question requires the respondent to reply with more information than a "yes" or "no" answer. |

|

| Closed-Ended | When you need a "yes" or "no" answer or when you want the other person to provide you with a specific answer from among a set of choices, use closed questions. Closed means that you only have specific options and no other choices. |

|

| Probing | After a respondent answers a question, you can probe to get clarification or more information. By asking "probing" questions, you can tailor the interview as it is occurring. |

|

| Mirroring | Reflect the previous content back to the interviewee. A mirror question can be used to probe for more information or to provide a summary for the interviewee to agree, correct, or expand upon. |

|

| Leading | Avoid leading questions. A leading question virtually guarantees that the interviewee will reply with the desired answer. For example, "Wouldn't you prefer X?" indicates what you want the interviewee to prefer. You do not find out what the interviewee really thinks. |

|

The basic questionnaire is a survey consisting of a series of questions and other prompts to gather information from respondents.

Questionnaires have advantages over other types of surveys in that they are cheap, do not require as much effort from the questioner as verbal or telephone surveys, and often have standardized answers that make it simple to compile data.

EXAMPLE

You might have a question with easy scorable multiple choice answers such as:Do you want to find out if members of the audience share the same attitudes or agree or disagree with your thesis? You can use a Likert-type rating scale of attitudes.

A Likert item is simply a statement that the respondent is asked to evaluate according to any kind of objective criteria; generally, the level of agreement or disagreement is measured. Often, five ordered response levels are used.

When using a questionnaire or using rating scales, it is wise to try them out on a small sample of your audience before you administer them to a large group. You can use the small sample to make sure that everyone understands the meaning of the questions and that you are getting useful information.

Look at the Likert scale in the following example to see the format of the typical five-level Likert item, which is:

Sometimes, you will learn information about your audience prior to your speech. In that case, it is relatively simple to incorporate what you know into your delivery and speech content. If your speech is already written and you receive information about your audience, it’s possible to make adaptations to your message as you prepare for your presentation.

However, there may be times when you do not have certain information prior to speaking that you learn during your presentation. While this scenario can certainly be nerve-wracking, it is not impossible to work with. In fact, a flexible speaker that can make adaptations at the moment is often the most effective speaker because they are able to adapt to the audience in front of them dynamically. After all, it’s not possible to know everything about your audience prior to your speech, and we should all try to be as flexible as possible with our delivery.

A public speaker can use information about the audience to adapt their message to the particular audience while preparing the speech. Demographic information helps the speaker anticipate the audience and imagine how they will respond to different aspects of the message.

While structuring the message, the speaker should keep their imagined, theoretical audience in mind and anticipate how they might respond to the speech as follows:

Speakers are encouraged to plan to adapt during the speech. With a face-to-face audience in a small room, the speaker can observe nonverbal reactions, such as looks of confusion or expressions of agreement or disagreement, and adjust the message accordingly.

The speaker can also encourage the audience to ask questions. Traditionally, the speaker asks for questions after the speech is finished; however, this is only sometimes the case. The speaker can guide the audience to ask questions throughout the speech by simply pausing between points or politely asking the audience to hold all questions until the end. If audience members hold all questions until the end, the speaker should be prepared for interruptions and rehearse accordingly.

With a larger face-to-face audience, a speaker may want to use an audience response system (ARS), also known as a clicker, to determine what the audience understands or their current opinions. ARS systems work with the audience's wi-fi-enabled notebooks, laptops, or other hand-held computers.

If the speaker's computer is also wi-fi-enabled, then they can display the responses on a screen while speaking and adapt the message accordingly. ARS systems can be used for large audiences anywhere in a classroom, lecture hall, or when speaking by teleconference.

Cell phones using SMS response systems are another way for the speaker to collect information and adapt during the speech. Cell phone-enabled response systems, such as SMS response systems, are able to take text inputs from the audience and receive multiple responses to questions per SMS.

For facilities that do not have the equipment to analyze the SMS data during the speech, the audience can send tweets to the speaker using a hashtag unique to the occasion or presentation. The tweets can be displayed as part of a back channel from remote audiences or members of large audiences using their smartphones, and the speaker can respond to the tweets or adapt his or her message in real time.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM "BOUNDLESS COMMUNICATIONS" PROVIDED BY BOUNDLESS.COM. ACCESS FOR FREE AT oer commons. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION-SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.