Table of Contents |

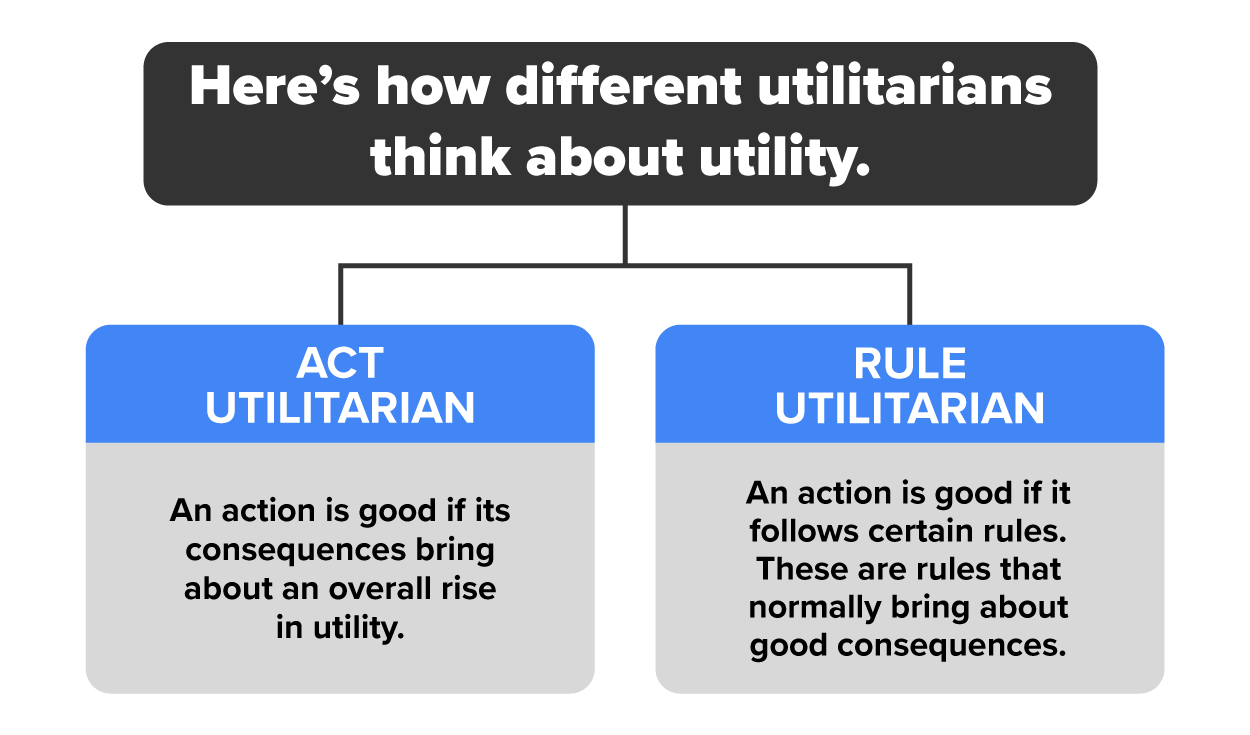

In an influential textbook published in 1959, Richard Brandt (1910–1997) introduced the terminology of “act” and “rule” utilitarianism. He later refined these in a 1963 article. Brandt laid out the terms this way:

"I call a utilitarianism “act-utilitarianism” if it holds that the rightness of an act is fixed by the utility of its consequences, as compared with those of other acts the agent might perform instead. Act-utilitarianism is hence an atomistic theory: the value of the effects of a single act on the world is decisive for its rightness. “Rule-utilitarianism,” in contrast, applies to views according to which the rightness of an act is not fixed by its relative utility, but by conformity with general rules or principles; the utilitarian feature of these theories consists in the fact that the correctness of these rules or principles is fixed in some way by the utility of their general acceptance. In contrast with the atomism of act-utilitarianism, rule-utilitarianism is in a sense an organic theory: the rightness of individual acts can be ascertained only by assessing a whole social policy."

One aspect in Brandt’s understanding is worth emphasizing. Rule utilitarianism carries with it an obligation to act in accordance with the rule. As we saw earlier in our discussion of permissibility in utilitarianism, act utilitarianism carries an obligation only to the extent that the agent feels regret for not acting to maximize utility.

You should be careful here with the term “rule.” You might think of it as something like a law, but we’re using it here to mean something more like a guide for action. If you find yourself in a certain situation, you can turn to the rule to help you decide what action you ought to take.

EXAMPLE

Consider these two rules: “If you have excess income, you should give it to charity” and “When at work, be nice to your colleagues.”Most of the time, act utilitarians agree with rule utilitarians, but this depends on the specific nature of a situation. Rule utilitarianism often will include an obligation when act utilitarianism would find that there is not any increase in utility from the action.

"On the rule-utilitarian theory, if we make a promise to a widow to care for her daughter, we are bound not just to the extent that we must do whatever will produce best consequences (so that we are bound, perhaps, to do just what we would otherwise have been bound to do if we had not made the promise); we are bound to do whatever it would have the best consequences for everyone to do in similar situations. This— especially in view of the value of people being able to rely on promises— may be to honor the promise in many situations for which act-utilitarians would not prescribe honoring the promise."

In this example, we see that a rule utilitarian would keep the promise even when in a particular instance, doing so does not result in increasing utility.

In other instances, we see that act utilitarians would act differently because a situation is an exception to the rule. Consider the rule that we shouldn’t damage other people’s property. If you damaged someone’s property for fun, the act utilitarian would likely agree that doing so would reduce utility, and thus would agree with this rule. But if you needed to break into an empty building to find shelter, the act utilitarian would disagree with following the rule because in this instance, more utility is the result of acting against the rule rather than following it. The benefit of shelter outweighs the harm of damaging property.

You can think of many other cases where an action usually does more harm than good but the balance changes under different circumstances.

EXAMPLE

Both types of utilitarians will agree that it’s bad to intentionally give a stranger wrong directions. But if you gave the wrong directions because you knew they were going to hurt someone at their destination, there would be disagreement. That’s because the act utilitarian sees that the benefit outweighs the harm in this instance: the benefit of saving someone from injury is greater than the harm of lying to someone. By contrast, the rule utilitarian would stick to their evaluation because they opposed this action due to the rule that lying is wrong.Act and rule utilitarianism have different strengths. As you probably already guessed, the strength of act utilitarianism is that it’s more adaptable. Think back to the example of damaging property. If you hold onto the prohibition on damaging property no matter what, you can overlook the utility it provides under certain circumstances. It makes sense that we should say that it’s good to break into an empty building when it means saving yourself from sleeping on the street.

The strengths of rule utilitarianism might not be so obvious, but if you think about how difficult it can be to calculate consequences, you’ll see its advantages.

IN CONTEXT

Imagine you’re walking along a bridge and you see someone is preparing to jump. If you decided to try to talk the person off the ledge, you could be following the rule “save a life when doing so doesn’t put your own life in danger.”

In this situation, it doesn’t seem appropriate to take your time, calculating all the potential benefits and harms of whichever course of action you take. Think about it: while you’re there tallying up consequences, the person could’ve jumped already.

As you can see, following a rule like this makes sense practically. Sometimes, you don’t have the time to try to calculate all the possible consequences of an action. Moreover, if you had already done research about suicide, you would probably find information to support this rule, such as evidence that most people who are saved are grateful and go on to have a life with many benefits. Figuring out a rule in advance can thus be very helpful for increasing utility. (It is also worth remembering, as we saw previously, that both Mill and Smart attempted to provide a defense against the “there is no time” objection that does not require accepting rule utilitarianism.)

Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.

REFERENCES

Brandt, R. (1959). Ethical theory. Prentice Hall.

Brandt, R. (1963). Toward a credible form of utilitarianism. In H.-N. Castañeda & G. Nakhnikian (Eds.), Morality and the language of conduct (pp. 107–143). Wayne State University Press.